We have to do a better job dealing with mental health in the academy. We really, really have to. The most recent information suggests that almost half of Michigan students, at the graduate and undergraduate level, have felt overwhelming anxiety or severe sadness or loneliness. The number hovers around 80% who have felt overwhelmed or exhausted in the past year. The reality is that students dealing with some sort of mental or emotional struggles are not outliers—they are the majority of our student body. We need to face this reality if we’re going to make our campus a healthier place for our instructors and our students.

In the fairly recent past, I’ve seen so many articles go viral in the limited way that things do among graduate students—that is to say, these weren’t trending on Facebook as a whole, I’m sure, but I saw them posted and reposted by so many of my own friends. To give only a short list of the posts, there was:

- Deanna Zandt’s wonderful comic essay about how medicating depression doesn’t equate to failure

- Toby Allen’s depictions of mental illnesses as monsters, giving a visible face to invisible problems

- Andrew Solomon’s powerful TEDTalk about his own depression

- Heart-breaking accounts of the challenges facing students dealing with medical leave for mental health issues at Yale and Duke and other schools

- The Guardian’s article about the culture of acceptance around mental health in academia

- A brave and candid Dewey Lecture by Michigan’s own Peter Railton

- And very many more

My Facebook friends, at least, seem very aware that this is a problem. And more than ever before, I see friends of mine who are willing to share their stories and their struggles and their pain, in hopes of encouraging people to get the help that they need. At this point, it seems clear that higher education, both at the undergraduate and graduate level, is a difficult place and mental health is something we very much need to discuss as an academic community. And, to be clear, I certainly don’t mean to suggest that there aren’t a lot of organizations working hard to start these discussions and to make meaningful changes. The resources are there (I’ve noted several at the end of this post, but there are many more initiatives, both on our campus and nation-wide). As a graduate student and as an instructor, though, it seems like there are a lot of available resources and a lot of talk about the problem, but that it can remain very much in the abstract. In the abstract, when everyone talks so much about the prevalence of mental health issues and the importance of destigmatizing them, it’s easy to start to think that maybe we have. If all of my friends and colleagues, online and in person, all agree on this point, then clearly it’s a consensus opinion, right? The world agrees . . . we’re making progress!

And maybe we are. But I think it’s important to recognize two things:

1) Just because some graduate students are talking to each other about mental health doesn’t mean we can take for granted that our students (or even faculty and staff) are having those same discussions.

2) Saying we need to destigmatize something isn’t the same as destigmatizing it.

We all know #1, but sometimes it’s easy not to really understand it. I would never suggest that academia is free of racism and sexism and all the evils of the world, but there are lots of ways that academia doesn’t reflect the rest of society. Many of my straight peers talk about partners instead of boyfriends/girlfriends, because it’s a non-heteronormative term. I can discuss microaggressions, gender-neutral pronouns, gender (and sexual) fluidity, ableism, the male gaze, privilege, and so many other things, and no one will accuse me of being “the PC police” or think I’ve made up a term. There are plenty of very real problems with the culture of academia, but it’s pretty undeniable that the conversations that are common among graduate students aren’t the conversations that are common everywhere. The reason this matters so much to me is that I need to remember that just because all my Facebook friends think something doesn’t mean that my students do.

I want to come back to that point in a moment, but first I want to talk about #2—words are important, and talking about the importance of destigmatizing mental health is an important step. However, talking about why it’s important to end racism hasn’t ended racism, and talking about destigmatizing mental health hasn’t actually destigmatized it. Nationally, we talk about mental health when there’s a mass shooting or when a celebrity commits suicide. That’s pretty much it: people who are struggling with mental health are stigmatized as either serial killers or suicidal. People are crazy or they’re normal. Mental illness is still very much seen as a weakness or a failure, rather than a disease, and there is an undeniable sense that talking about your own mental illness is akin to making excuses. In the abstract, we all think that there’s no shame in mental illness, but we worry what will happen in our departments or in the fiercely competitive academic job market if we admit to struggling with depression or anxiety—who will want to hire us over one of the other 100+ candidates for a job if we admit that we can’t hack it?

So, this leads me to a goal that I have as I start this new semester and this new year. In my capacity as an instructor, I want to take a much more active role in talking with my students about the realities of mental health at the university. If even among graduate students and faculty, we can’t destigmatize mental illness and have the sort of conversations that academia so desperately needs, how can we expect our students to feel comfortable reaching out for help? We have statistics on university students nationwide and Michigan students in particular, and they are struggling with mental health issues at an above-average rate. They are stressed and they are anxious and they are often depressed and handling it in unhealthy ways—high-risk or self-destructive behaviors, disordered eating, dangerous drinking.

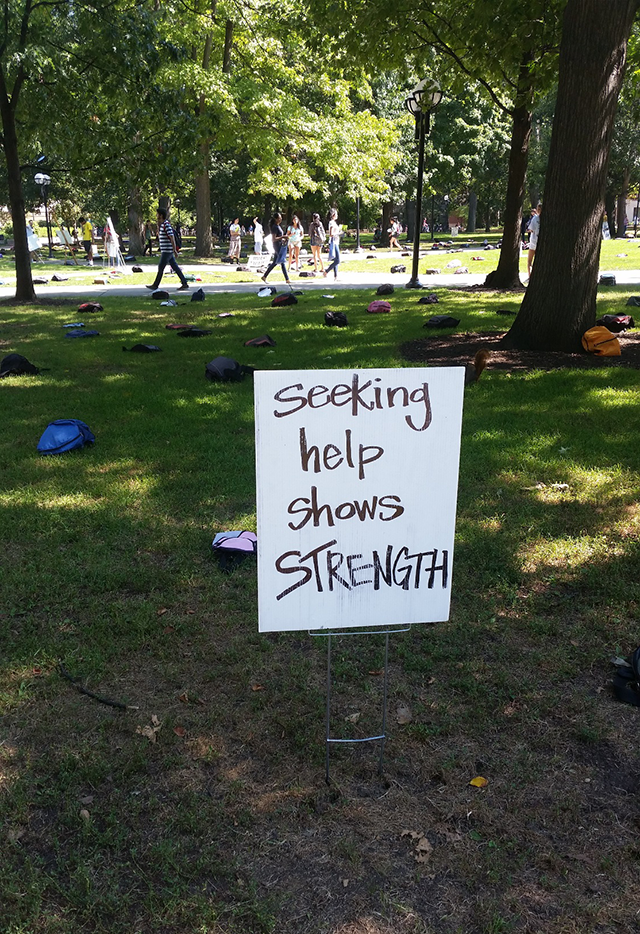

Caption: Image from Send Silence Packing, an event organized by Active Minds UM (AMUM) on September 17, 2015. Each backpack represented one of the 1,100 college students who die by suicide each year. The exhibit is part of a national attempt to start to change the conversation around mental health on campuses.

Graduate students and professors surely can’t solve everything, but I would encourage everyone to think about tackling mental health in classes in a more direct way. Winter term is just starting, and winter is a long, cold, dark time in Michigan. This semester (and every semester), I plan to preemptively discuss physical and mental well-being with students as much as possible. I don’t know that it will change the world, but I do know that I’ve had so many students who only come talk to me about how they’re doing when they’re failing the course and their grades are irreparably harmed. I recognize that mental health is a complicated topic, and the causes of emotional and physical trauma facing students (graduate and undergraduate, not to mention both tenured and adjunct faculty) are vast and varied and beyond the scope of this post and the scope of our jobs as instructors, sometimes. There are broad, systemic issues that contribute to campus climate and student well-being, and while I do think we urgently need to address these, these are problems that I can’t personally fix. Without minimizing the importance of broader, institutional changes, I personally want to make changes in my own teaching and the interactions I have with students. I want to do something.

My goal for adding this into my teaching really has two parts, both of which I hope others will consider in their teaching as well:

1) To make sure that my students know that any mental illnesses they’re facing are just as legitimate as physical illnesses—whether they’re struggling with bronchitis or depression, those are both real struggles that will be taken seriously. And, as with any diseases, I don’t need any more specifics than they want to share. I will work with them to help them make up assignments if they are unwell. Period.

2) To make sure my students know that having a mental illness does not make them “crazy,” and that taking appropriate care of their mental health isn’t a sign of weakness or failure, but is the sort of normal, responsible thing that healthy adults need to do—like making dentist appointments. I plan to talk openly about how I love to go visit the CAPS Wellness Zone and study in front of a sun lamp or read in a massage chair, or about how, for me, running is at least as much about my mental well-being as my physical well-being.

I would love to hear any specific ideas other instructors have—that have worked or that you plan to try. I don’t know that I have the right approach figured out, but I do know that we as an institution need to be better, and I plan to do everything I can to make this a part of my own teaching in the future.

Additional on-campus resources:

- CAPS (now with after-hour resources)

- Embedded CAPS Counselors across campus who serve graduate students (at Rackham: Lana Tolaymat, Ph.D.)

- Campus Mind Works

- Mental Health Work Group (MHWG)

- Department of Psychiatry Mental Health Clinics (including the Depression Center)

- Mental Health Services at UHS

- Mary A. Rackham Institute—U-M Psychological Clinic

- U-M Psychiatric Emergency Services (734-936-5900) or dial 911

Caption: Also from Send Silence Packing (September 17, 2015). For personal stories from students sharing their own experiences with treatment and recovery, you can check out Active Minds’ Step Inside My Head.