History

The Barbour Scholarship program was originally endowed by Levi Barbour in 1917 to support female graduate students from Asia and the Middle East.

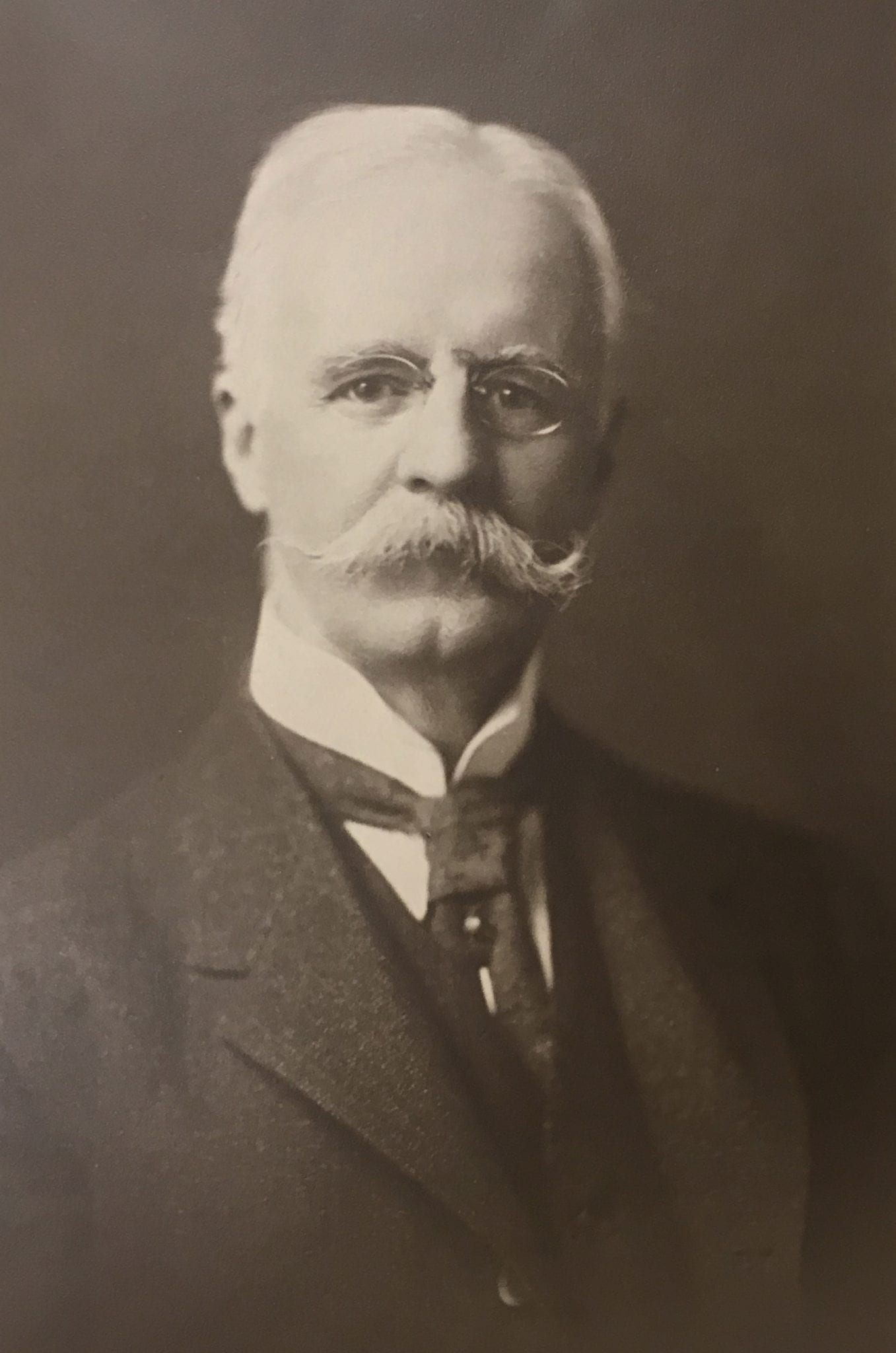

Legacy of Levi Barbour

One of the University of Michigan’s oldest, most prestigious, and most unique awards, the Barbour Scholarship has supported female students from Asia since 1917.

A prominent Detroit lawyer, real estate developer, and philanthropist, Levi Lewis Barbour received degrees from the University of Michigan in 1863 and 1865. He left a legacy at U-M as a champion for the education of women, including through advocacy as Regent (1896-1902; 1906-1912) and through his donations of the university’s first facilities for women, Barbour Gymnasium and Betsy Barbour House. But the University project that interested him most was the Barbour Scholarship.

Travelling in Asia in 1913, Barbour met three women in China and Japan who had been trained in medicine at the University of Michigan. Inspired by their remarkable contributions to those countries’ welfare and development, he cultivated his vision to endow a scholarship to prepare Asian women as leaders in their home countries and to facilitate understanding between Eastern and Western cultures.

The scholarship began as an intimate program for a handful of women, the first of whom lived in Barbour’s home. Since then, it has malleably weathered global upheavals and financially lean times, shifted focus to graduate students, and transitioned from a small recruitment scholarship to one supporting scholars from an array of nationalities and academic disciplines on U-M’s campus.

In the past century, more than 700 extraordinary women from over 25 countries have been appointed as Barbour Scholars. They have been university presidents and educators, senators and ambassadors, researchers and industry leaders, and more. Currently, around 200 reside in the U.S. and 261 can be found abroad—Levi Barbour’s living global legacy.

The Early Years, 1917 to 1925

- Levi Barbour travels to Asia and meets Mary Stone, Ida Kahn, and Tomo Inouye, U-M alumnae and physicians who inspire the Barbour Scholarship

- Barbour establishes the Barbour Scholarship in 1917 and secures its financial stability with two gifts of $50,000—totaling approximately $2 million in 2017 dollars—and a bequest of real estate.

- The first fifty-seven Barbour Scholars come to Ann Arbor, most from China, India, and Japan. They comprise the majority of international students at U-M.

While traveling in Asia in 1913, Levi Barbour visited with U-M alumni in Singapore, Shanghai, Beijing, Manchuria, and Tokyo. In Japan and China, he met three medical school alumnae who had established successful practices as medical missionaries in their native countries: Mary Stone (born Shi Meiyu) and Ida Kahn (born Kang Cheng), both of whom graduated in 1896, and Tomo Inouye, who graduated in 1901. Barbour was impressed by the lengths they’d taken to obtain a higher education, by their talent, and by their impact in providing some of the only medical care available in their areas. These meetings solidified and shaped his existing interest in bringing female international students to U-M.

In a letter to President Hutchins, Barbour explained his intent: “The idea of the Oriental girls’ scholarship is to bring girls from the Orient, give them an Occidental education and let them take back whatever they find good and assimilate the blessings among the people from which they come.” Barbour felt that women “should have every facility for education and every right and privilege to exert their influence to the fullest extent.” He saw a need for professionally trained women in Asia and recognized the value of greater cross-cultural understanding between Asia and the United States—both significant at a historical moment when anti-Asian prejudice and immigration restrictions were increasing in the United States and when Asia was striving rapidly to modernize.

Barbour brought Kameo Sadakata and Mutsu Kikuchi to Michigan under his own care in 1914, and the Barbour Scholarship was formally established in 1917 when the Board of Regents accepted Barbour’s gift of $50,000 to endow scholarships for young women from Asia and the Middle East. Barbour further solidified the program’s financial foundation with another gift of $50,000 in year—totaling approximately $2M in 2017 dollars— and with his bequest of real estate holdings in Detroit to provide renewable income.

Early program reports note the recruitment challenges posed by women’s irregular access to academic preparation and highlight the dramatic obstacles that early scholars overcame, even though most were from privileged families: some disguised themselves as boys to obtain early education, left the segregated seclusion of purdah in India, or resisted the practice of foot binding in China. Arrival at Michigan posed its own challenges; the Michigan Daily reported on a Barbour Scholar’s travel as an event of interest to the entire campus, and transition to life in Ann Arbor could be difficult. Struggles were often but not always met with sympathy by campus officials.

Levi Barbour lived to see the scholarship begin to grow. In 1922, twenty-two young women from Japan, China, and India had received the scholarships. Just three years later, the total number had reached fifty-seven. Barbour had met many of them personally, and those who were in America at the time of his death in 1925 attended his funeral in Detroit and conducted a memorial service for him at Betsy Barbour House.

Wherever we went around the globe, Barbour Scholars were active and prominent. We are proud of the contributions they are making everywhere, not only in research, in education, in the professions, and in the home, but especially in the more essential and more subtle influence toward better international understanding and friendship, stepping stones to world-wide security and peace for all the lands linked together by the growing family of Barbour Scholars.

Growth and Development, 1926 to 1941

- The Barbour Scholarship committee began giving preference to applicants who had graduated from a college in Asia and were seeking a graduate degree at U-M.

- In June of 1928, Yi-fang Wu and Maria Lanzar became the first two Barbour Scholars to receive Ph.D.s, Yi-fang in Biology and Maria in Political Science.

- Despite the impact of the Great Depression, the number of students increased significantly in the 1930s.

By the mid-1920s, most Asian nations had established women’s and co-educational universities; however, most Asian women had to go to the United States or Europe for advanced degrees. The Barbour Scholarship committee began to give preference to applicants who had graduated from a college in Asia and who were seeking a graduate degree at the University of Michigan. By 1928, the majority of applicants sought advanced degrees, in June of that year the first two Barbour Scholars received the degree Doctor of Philosophy: Yi-fang Wu in Biology and Maria Lanzar in Political Science (the first awarded to a woman at U-M).

Despite a declining endowment through the Great Depression, the number of students increased significantly in the 1930s. Between 1928 and 1933, a program of one-year Barbour Fellowships was offered in addition to the renewable scholarships for students. Extended by invitation to ten “Oriental women of noteworthy achievement in scholarship and service in the Orient,” the fellowships offered one year of paid professional leave to mature scholars and leaders to “pursue special lines of investigation and research.”

During these years, the scholars formed a tight-knit community. The scholarship secretary, Professor Carl Rufus, recounts regular social gatherings, including potluck dinners featuring scholars’ recipes from home and festive events featuring “skits and stunts, some of which revealed unsuspected talent, or lack of it, by nearly all who attended, including the usually dignified deans.” One Barbour Scholar described the Rufuses as like mother and father to the Scholars, and alumnae overseas remained in touch through a regular newsletter that shared career and scholastic updates.

WWII and the Program, 1942 to 1945

- In the U.S. and abroad, Barbour Scholar alumnae played significant roles in humanitarian efforts.

- Global turmoil made it difficult or impossible to bring scholars from some areas.

- Carl Rufus reiterated the importance of maintaining the scholarship’s mission through global turmoil: “Our Barbour Scholars on the other side of the oceans will be well qualified after this terrible experience to assist in postwar reconstruction and in building a better world.”

Levi Barbour believed a strong commitment to Asian women’s education would promote international peace, but the outbreak of the Second World War had a devastating impact on many of the countries served by the Barbour Scholars Program.

In the U.S. and abroad, Barbour Scholar alumnae played significant roles in humanitarian efforts. At Ginling College in 1937, Blanche Wu chose not to evacuate and helped transform the campus into a relief camp for over 10,000 women and girls in the wake of the Nanking Massacre. At Michigan in 1939, Physician Poe-Eng Yu became the first non-citizen Chinese woman in the U.S. Army and also the first Chinese woman doctor to receive a commission.

Fractured communication and global turmoil made it difficult or impossible to bring scholars from some areas during these years. Though the selection committee ordinarily awarded the scholarship exclusively to students living in Asian countries, they appointed a handful of Japanese-American, Chinese-American, and Chinese-Canadian Scholars in addition to scholars both born and residing in Asia.

Carl Rufus wrote in 1942 about concern on campus for endangered and displaced alumnae, and he reiterated the importance of maintaining the scholarship’s mission through global turmoil: “Our Barbour Scholars on the other side of the oceans will be well qualified after this terrible experience to assist in postwar reconstruction and in building a better world.”

As the war drew to a close, Rufus projected with hope the postwar horizons for the program and the future of international relations : “More and more prospective Barbour Scholars will see means of obtaining travel to the United States; people of the United States will become less provincial and broaden out into hemispheric patterns. This international intimacy will surely affect the possibilities for a truer and more permanent peace.”

Post WWII, 1946 to 1969

- Barbour Scholars began coming from Vietnam, Burma, Malaysia, and Indonesia, along with the newly formed political entities of Pakistan and Bangladesh.

- The Barbour Scholarship Committee officially classified the Barbour awards as graduate scholarships in 1948.

- By 1957, the International Institute of Education recognized the Barbour Scholars Program’s impact with a special citation accepted by President Hatcher.

After 1946, additional countries produced Barbour Scholars: Vietnam, Burma, Malaysia, and Indonesia, along with the newly formed political entities of Pakistan and Bangladesh. Professor of English Frank L. Huntley succeeded Professor Rufus as program secretary upon Rufus’s retirement in 1946, and his leadership brought significant changes to the program. Huntley lifted the restriction against marriage for scholarship holders, and the Barbour Scholarship Committee officially classified the Barbour awards as graduate scholarships in 1948.

As the world recovered from the war, the Barbour Scholarship increased in renown. In 1947, the American Embassy and the United States Information Service offices in China were, according to a letter from the Assistant Cultural Relations Officer at the American Embassy in Nanking, “deluged with requests for information concerning scholarships for study in the United States.” That year, the Barbour Scholarship received 150 applications from China alone. By 1957, the International Institute of Education recognized the Barbour Scholars Program’s impact with a special citation accepted by President Hatcher.

Though the program enjoyed a wide reputation, financial constraints severely limited the number of new scholar appointments in the 1950s; 1951 marked the only year in program history with no new scholars. In 1956, the University sold the Detroit real estate holdings whose dwindling profits had made up the majority of the program’s operating budget to secure the program’s financial stability.

The comparatively smaller group of Barbour Scholars continued to create a supportive community on campus through Huntley’s tenure in the 1950s and 1960s. Huntley and his wife held monthly teas for scholars in addition to other festive events at their home.

Modern Barbours, 1970 to Present

- The program shifted from a renewable recruitment scholarship to a one-term fellowship providing needed financial support to graduate students already at the University.

- Since Scholarship administration began tracking Scholars’ areas of academic focus in 1970, scholars have pursued 86 different degree programs.

When Frank Huntley retired in 1970, he proposed changes to the Barbour Scholarship’s administration to help it meet new needs. The program shifted from a renewable recruitment scholarship to a one-term fellowship providing needed financial support to graduate students already at the University. These changes allowed the program to distribute support more widely, helping to launch the careers of Asian women from a broader array of countries and academic disciplines.

Since the University began tracking Scholars’ areas of academic focus in 1970, they have pursued 86 different degree programs. The top ten programs with the most Barbour Scholars include: Architecture & Urban Planning, Psychology, Electrical Engineering & Computer Science, Anthropology, Linguistics, Sociology, Mathematics, Education, Comparative Literature, and Social Work.

Barbour alumnae have played important roles in the political, educational, industrial, and social development of the world, and they have made important contributions to their scholarly fields. As global citizens, Barbour alumnae serve as faculty members, senators, researchers, and industry leaders throughout the world—in United States, the Philippines, China, Taiwan, Thailand, the Republic of Korea, India, Hong Kong, Japan, Lebanon, Israel, Singapore, Turkey, Sri Lanka, Iran, Egypt, Australia, the Netherlands, Bangladesh, Canada, and the United Arab Emirates. Each year, new Barbour Scholars attend a reception along with current scholars, local alumni, and faculty advisors.

Many modern Barbour Scholars, like earlier counterparts, have overcome obstacles in attaining their educations. Some were denied intellectual and academic freedom in their home countries. Others faced oppressive restrictions placed on women by totalitarian regimes. Still more endured martial law or violent war. All made the choice to travel far from home for their education.

The Barbour Scholars Program has created a century of global exchange by providing academic opportunities to a diverse group of Asian women united by their commitment to academic excellence, professional ambition, and service to society.

Bibliography

The sources used for this history are located in the Barbour Scholar Program archives at the University of Michigan Rackham Graduate School and in the Bentley Historical Library, in addition to the sources listed below.

Bordin, Ruth B. “Levi Lewis Barbour—Benefactor of University of Michigan Women.” Michigan Quarterly Review. Volume 64, Number 36. Winter 1963. 36-40.

Clarke, Kim. “The Barbour Scholars.” Leaders & Best: Philanthropy at the University of Michigan. Winter 2003. 24-5.

Faerber, Karen Irene. “The Levi L. Barbour Scholarship for Asian Women.” Master’s thesis. Eastern Michigan University. November 16, 1994.

Huntley, Frank L. “Eleven Years of the Barbour Scholarship (1946-57): A Report to the President and Committee.” Unpublished paper. Bentley Historical Library.

Mills, Harriet C. “Barbour Scholarships at Michigan.” Rackham Reports, Volume 10, Number 2. Fall 1984.

Rufus, W. Carl. “Barbour Scholars Around the World.” May 10, 1937. Unpublished paper. Bentley Historical Library.

“Twenty-Five Years of the Barbour Scholarships.” Michigan Alumnus Quarterly Review. Volume XLIX, Number 11. December 19, 1942.

Singh, Avtar H. “Barbour Scholarships for Oriental Women at the University of Michigan 1917-1955.” Unpublished paper. Bentley Historical Library.

Tobin, James. “The New Women of China.” Medicine at Michigan. Fall 2010.

Xiong, Rosalinda. “Ginling College, the University of Michigan and the Barbour Scholarship.” Unpublished research paper. United World College of Southeast Asia in Singapore.