During 2012 we observed the centennial of the founding of the Graduate School at the University of Michigan with special events, large-scale projects and funding opportunities. However, 1912 marked only the formal institution of a graduate school at U-M: it certainly was not the beginning of graduate education at our university. This was immediately evident as we began planning one of the projects we’d use to celebrate our Centennial.

We knew it would be fun to put together an illustrated timeline—and were delighted with what we found. Planning the timeline brought up the question: are we talking only about the history of the Graduate School only or about graduate education at Michigan? We opted for the latter since graduate education here began when the first graduate degrees were awarded at U-M in the 1840s. After all, observing the centennial was not limited to a building or an administrative decision: we were and still are celebrating the entire tradition.

We recognized the opportunity to tell our story in another way, too. No individual at the Graduate School had the time to write a full history of graduate education at Michigan. Instead, the timeline we put together provides a summary of developments for each decade, photographs from the University archives and, on the lower right-hand side of each webpage, a short listing of notable events taking place during that decade. Originally, the timeline appeared regularly during 2012 as posts to the Rackham Blog.

Writing this encapsulated history for each decade also provided the opportunity to answer some of the questions many students, staff and faculty have shared. What does the Graduate School actually do? Why do we need a Graduate School? Did the Graduate School always have that role at the university? What does the Graduate School at U-M do that’s different from other graduate schools at other universities?

Finding material was easy, as anyone who’s even taken a look at the Bentley Library’s website will know. It’s an incredible treasure and if you have an interest in U-M in the recent or distant past you should take a look at what they have to offer: http://bentley.umich.edu/.

The sources used most extensively in developing this narrative summary of graduate education as it developed at U-M over the past two centuries include The Making of the University of Michigan, 1817-1992 by Howard H. Peckham, edited and updated by Margaret L. Steneck and Nicholas H. Steneck (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, 1994). The other resources are digital in format and available through the Bentley Library’s website. If you want to learn more, just click on any of the following:

- The University of Michigan An Encyclopedic Survey in Four Volumes, edited by Wilfred B. Shaw. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/AAS3302.0001.001

- History of the University of Michigan, by the late Burke A. Hinsdale, with biographical sketches of the regents and members of the university Senate from 1837 to 1906, edited by Isaac N. Demmon. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/ADX8153.0001.001

- The Bentley Image Library. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/b/bhl

- A Chronicle of Graduate Education 1845 to 1982, Mary M. Easthope. https://rackham.umich.edu/about_us/what_is_rackham/chronicle/

1840s

Mason Hall, the first University building devoted to instruction, was known as the University Building upon completion in 1841, in time for fall classes. It was both a dormitory and classroom facility. It was named after Governor Stevens T. Mason in 1843.

Although the University of Michigan was founded in Detroit in 1817, only after it was reorganized as a state university and relocated in Ann Arbor in 1837 did it begin to fulfill its promise of grand ideals from 20 years earlier.

During these early decades the Regents of the University devoted time to planning, seeking funds for construction, and putting up the first buildings to house the resources that must be in place before goals could be pursued. The Regents had the foresight to invest in resources for the buildings—books, laboratory specimen and equipment, professors—while still fund-raising for the construction of buildings and often in advance of any significant student presence.

One of the four original buildings on campus, located on South University, east of the Presidents’ house, where Clements Library now stands. Used as a professor’s house from 1840 to 1877.

The early building campaign featured the construction of four homes for professors that might also serve as museums. (One of these, on South University, remains the home of the University’s president.) Next, the Main Building was completed in 1841 and contained classrooms, student residences, library and museum collections. The first courses on the collegiate level were offered that year to a student body that consisted of six freshmen and one sophomore. By the end of the decade the campus also featured the Medical Building, also known as South College because of its relationship to the Main Building.

During the opening years the curriculum was of the type typically offered to the wealthy and intellectual elite. Courses included very traditional fare found elsewhere in the American collegiate model: classical literature, rhetoric, and grammar; basic instruction in natural science, algebra, and geometry. Americans in the first half of the nineteenth century were just beginning to question the type of education suitable for the young democracy.

The first reference to graduate education at the University, what was then termed a postgraduate degree, was in 1845. It is found in a resolution adopted by the Board of Regents that year: “No candidate for the second degree of Master of Arts shall receive this honor unless he has preserved a good moral character, and previously to the Commencement, has signified his desire of the same to the Faculty.” The first 11 students graduated from Michigan that same year. The Honorary Master of Arts was established by the Board of Regents in 1847 and the first two Master’s degrees earned through coursework were given in 1849 to Merchant Goodrich of Ann Arbor and Winfield Smith of Monroe, MI.

1850s

The first medical building, built 1850, with an addition in 1864, used until the West Medical Building was completed in 1903.

Americans in the mid-nineteenth century often held competing notions of the basic purpose of education. It was not uncommon to hear some version of the argument that when it came to education in general, practical training and intellectual pursuits should be entirely distinct. On our campus and many others in the nation there were some who held the view that education was intended to perfect the intellect of the elite, and there were others who sought to adopt the best aspects of differing educational systems to serve the needs of all in our democratic society.

When the State Legislature developed a new constitution in 1851, it reorganized the definition of the University of Michigan, stating that it should have departments: literature, science and arts; medicine; law. Other departments were expected to emerge when need and funding allowed. While the Medical Department was underway at the beginning of this decade, the Law Department only began to form in 1859. At this time, unlike today, pursuing medicine or law was not a type of graduate study. Young men (and the occasional outrageous woman) drawn to medicine or law typically entered into a course of study directly from secondary school that focused on practice more than abstract theory. Both had a very significant apprentice or internship component in learning by doing.

Henry P. Tappan, President of the University of Michigan from 1852 to 1863.

This decade begins to see the emergence of graduate education. In 1852 University President Henry P. Tappan was eager to promote the postgraduate education available to those who had attained B.A. or B.S. degrees. Tappan was a national leader among those who believed the colleges and universities should have an educational system similar in some ways to what was provided in Germany. He attempted to introduce an emphasis on research and learning formats beyond the typical rote memorization.

There were indicators, too, that interest in graduate education was growing among students: in 1854 the number of master’s degrees granted jumped to eighteen from four in the previous year.

By 1858 more stringent rules were adopted for granting Master of Arts and Master of Science degrees upon examination. They required that students pursue a course of studies, pass an examination, and compose a thesis, according to a plan worked out by President Tappan. The first degrees earned through examinations were granted the following year.

President Tappan was a man of vision and conviction regarding the value of graduate education. In his report to the Regents in 1859 he stated: “In these higher courses we’re advancing to the scope and dignity of a true University and maturing the noble plans of the founders. Nor need we despair of success. The more we enlarge our facilities of affording education, the more we extend our influence. These Institutions will ultimately command the highest success.”

1860s

Courthouse Square in Ann Arbor on Sunday April 15, 1861 where Dr. Tappan announced the news that Fort Sumter had been fired upon.

Few Americans think of this decade without the dominating presence of the Civil War. The rapidly growing town of Ann Arbor and its University life certainly was not removed from its effects. It was also a decade that saw important developments in postsecondary education across the nation.

At the start of the decade the population of Ann Arbor numbered around 5,000. Political opinions on campus and in the community ran the spectrum. But in 1861 at news about Fort Sumter, President Tappan urged students to stand by Lincoln and support the Union cause. Ann Arbor had a militia company that was called to service in April. University students quickly formed three more companies and from there involvement grew as increasing numbers left campus to join in the war effort. By the end of 1865 the number of alumni and students who served for the Union was more than 1,800. Only 61 were killed in action; a notable 431 served as surgeons.

The marks of the war were evident in other ways. For example, a professor began lecturing on military engineering and tactics in 1861 and a Chair of Military Engineering was established that year. Mining engineering was first offered in 1864 and Mechanical Engineering in 1868. The study of pharmacy began in the Literary Department in 1868 and was so successful it became a separate department in 1876. These changes indicate that education at Michigan was moving from rote learning or an apprentice model to an advanced curriculum centered on research, with a more immediate focus on applied research.

The State Street side of campus, showing Mason Hall, South College, and Haven Hall.

This interest in the practical component of education was behind the passage in Congress of the act which allowed for the creation of land-grant colleges across the nation. As the Act of July 2, 1862 (Morrill Act), Public Law 37-108, states the purpose was “without excluding other scientific and classical studies and including military tactic, to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts, in such manner as the legislatures of the States may respectively prescribe, in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life.” Here in Michigan this institution was the State Agricultural College which later became known as Michigan State University.

During this decade few students who attended the University were involved in graduate studies. Rather, its significance is that Michigan’s leadership focused on expanding the resources that contributed to the University’s popularity with researchers in later decades. The Medical Building was enlarged; the first university hospital in the country was established here; major improvements were made to the Observatory; President Haven sought endowments for professorships, the museum and library. By the end of the decade the Legislature granted increased support and though later this was limited, it marked acceptance of the principle that state aid should be a given.

The size of the student body increased as expected in 1865-1866 with the end of the war. Enrollment was 1,205—making the University of Michigan the largest university in the country. By the end of the decade the Literary Department offered more courses of study than almost any other university in nation. The options included classics, science, civil engineering, mining engineering, and pharmacy. Two-thirds of the student body were from other states, forty-one students were from Canada and four from other nations.

1870s

Ladies Crew Team on the Huron River

The decade opened with the Regents taking the first serious turn onto the path that would become one of the distinctive hallmarks of our University: access to higher education for all. In 1870 the Regents formally stated that study at the University of Michigan was open to anyone who “possesses the requisite literary and moral qualifications.” This meant opening the door to women, to students from other states, from other countries and to races other than white. That year 34 women were admitted to the University. While it is true that there were at least a handful of African Americans enrolled in the two prior decades noting race in the records was not typical at this time.

In other ways, too, it’s in the 1870s that we begin to see real change largely due to the leadership of President Angell. When he assumed this position in 1871 Angell had not articulated a plan for reforming the model of postsecondary education available in U.S. universities. At this time the University of Michigan consisted only of the Medical, Literary and Law Departments. Of the nine buildings on campus four were houses for professors. There were some 1,200 students and 35 faculty members. However meager that appears nowadays, for contemporaries it was an imposing institution poised for future growth. In fact, it was the largest university in the United States at that time.

By 1874, Angell had persuaded the Literary Faculty of the value of awarding master’s degrees to those who completed a bachelor’s degree, did “good work in post-graduate studies” under the direction of faculty, and passed final examinations. This was slow to catch on in actual practice, however, and some master’s degrees continued to be awarded through coursework alone until the mid-1880s.

As a result of a growing emphasis in the U.S. on serious study, often influenced by European models in which university degrees were followed by original research, a provision was made to grant the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to those who studied for at least two years after obtaining a bachelor’s degree. The first Doctor of Philosophy degrees at the University of Michigan were awarded to Victor C. Vaughn and William E. Smith in 1876. Their dissertations were titled “Quantitative Separation of Arsenic From Each of the Metals Precipitated by Hydrogen Sulphide in Acid Solution,” and “The Zoology of Anoura and Caecilia,” respectively.

School of Dentistry, 1875-1877

The growth of public education at Michigan was also evident in the emergence of new Departments within the University in areas we now consider to be graduate programs. The Dental Department opened in 1875 and the Pharmacy Department in 1876. Both were innovative in that they did not train students for a mechanical trade. Rather, like the post-baccalaureate education in Germany, they were solidly based in the latest scientific knowledge and promoted research. These Departments attracted a noticeable number of students from Europe.

1880s

University Museum, 1880-1881, facing State Street

Graduate education begins to emerge during this decade on a model that is more familiar, and more rigorous; its appeal is evident in the accelerating popularity of master’s and doctoral degrees. The leadership at U-M experimented throughout the late nineteenth century with adaptations of systems used elsewhere in the U.S. and Europe. At the same time, expanding resources on our campus made possible the pursuit of advanced learning in an increasing number of fields.

For example, in 1881 the new museums building was completed. This housed what were in fact six separate museums, one each for fine arts and history, applied chemistry, medicine and surgery, dental surgery and natural history. The collections were established and then expanded through amazing donations from faculty, leadership and alumni who traveled the world and shared the fruits of their purchases and discoveries with the university. Similar enlargements and improvements occurred in the laboratory facilities. The library used in the early decades of our history was quickly outgrown. The new Library was completed thanks to state appropriations in 1883 and quickly expanded through additional state appropriations and personal gifts.

June Rose Colby is the first woman to receive a Ph.D. upon examination. She becomes professor of English at Illinois State Normal School. Photo courtesy of Dr. JoAnn Rayfield Archives.

With these impressive resources at hand, presidents, faculty and the Regents turned in earnest to consider how best to make use of them with the most modern research methods. The central complaint was that study at the University was little more than additional rote learning of the type favored in secondary school and still dominant for those seeking a bachelor’s degree at most American universities. The fear was that Americans would continue to move to England and Germany for a serious advanced education and postgraduate studies. Improvement was sought through a shift in emphasis to new modes of instruction and investigation into assigned topics.

Beginning in the prior decade professors began to favor, instead of the traditional recitation, the lecture model accompanied by set topics for further investigation in writing. At the same time President Angell promoted what he termed the seminary system—more familiar to us as learning in small seminars. Limited to a small group of students, the seminar would meet regularly and at each session a student presented a paper on a prescribed topic and was critiqued by another student. The credit hour system came into use and undergraduate students had a wide number of electives from which to choose.

A doctorate could only be pursued by one who had received both bachelor’s and master’s degrees. It did not require a set number of courses but rather that the student pursue intensive studies under the guidance of a faculty committee in a focused set of topics.

During this decade 116 graduate degrees were granted, a growing number of them to women. In 1886 June Rose Colby became the first woman to receive Ph.D. by examination (English Literature). Considering the extended years of study required, and that at this time no fellowships were available, this speaks to the desire to pursue higher learning at the graduate level.

1890s

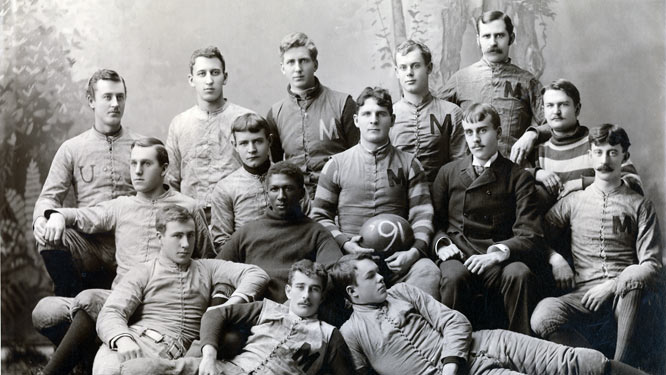

University of Michigan Football Team, 1890

In 1890 the University of Michigan once again edged out Harvard to hold the distinction of being the university in the United States with largest enrollment. There were 2,420 students on our campus at that time and the reasons for attracting such numbers are many. The costs of tuition and housing were relatively inexpensive, especially compared to private schools on the east coast, and this was due in part to improved state funding. We could boast an impressive faculty that included many authors of textbooks that were widely used in high schools and college; this in turn promoted our reputation. Because of the investment in faculty talent an extensive course selection was available. Libraries, museums and laboratories seemed to multiply annually. In addition to the wealth of academic resources, university life featured a student weekly newspaper, frequent concerts and plays, collegiate sports teams, nine fraternities and three sororities.

Dr. Ida Kahn was an early graduate of the Medical School, and one of the three women who inspired Mr. Barbour in later years to establish what was then called the “Levi L. Barbour Scholarships for Oriental Women.”

Only about half of the students came from in state. The University of Michigan was a thriving institution with a prominent national reputation. Indeed, this reputation was beginning to grow in other countries, too, and those who came from abroad were here for graduate and professional studies. In large part this was due to the missionary work carried out in Asia throughout the nineteenth century. Another conduit developed when President Angell took a leave from the university in 1880 to act as the U.S. Minister to China in 1880-81. He was instrumental in promoting the opportunities for Chinese students in Ann Arbor.

While from today’s perspective the number of students of color was painfully small, nonetheless they too enjoyed an increasing presence at Michigan. Even though recordkeeping at the time typically did not always note this aspect of student identity, photographs of contemporary student life speak to their presence. A quick sampling of the Bentley Image Bank shows faces that reflect the increasing diversity of our students. Similarly, the presence of women continued to grow steadily. Of those 2,420 students on campus in 1890, 445 were women. Among the 84 candidates for higher degrees there were 22 were women.

As Michigan’s reputation and size grew, so did the number of specialized Departments established within the university. By the end of the decade the University of Michigan consisted of the Departments of Literature, Science and Arts, of Medicine, Law, Political Science, Engineering, Nursing, Dentistry, and Pharmacy. And a Graduate School was in the making. In 1891 President Angell first promoted the need for an organization that could properly attend to the nature of graduate education. The next year faculty in Literature, Science and Arts decided to establish a graduate Department to appropriately supervise graduate study and the development of advanced courses. Leadership was established in an Administrative Council with the university’s president as chair and the first council consisting of the heads of programs within the Department. By the close of the decade it was increasingly clear that a lack of funds kept many students from taking part in graduate studies. In 1899 a committee, formed to review the need for graduate fellowship support, acknowledged the urgent situation.

When the University of Michigan was founded in Detroit in 1817 it was modeled on a centuries’ old pattern of rote studies for the elite in the seven liberal arts. Yet as the university was poised for a new century the fundamental structure emerging was the modern research university that retained the best of tradition and seized on innovation.

1900s

There were 90 students enrolled in the Graduate Department of Literature, Science and Arts at the opening of the twentieth century. On the face of it this seems to indicate little interest in research on campus. Yet this is misleading. Remember that research and post-graduate studies were carried out in all the schools on campus though only one school had a formal department for graduate education. Administrative struggles on campus for control of graduate studies, and an increasing gap between the number of students who wanted to continue on with their studies and the availability of faculty and funds to make this possible, served to constrain the expansion of graduate education at U-M.

Surgery and anatomy class, ca. 1900

Interior of the Chemical Laboratory, ca. 1900

Laying the cornerstone of Alumni Memorial Hall, 1908. The building was to house the University’s growing art collections which at the time were housed in the Library.

The rapidly growing interest in and importance of research were signaled in other ways. The Society for the Promotion of Research at the University of Michigan, later known as the Research Club, was established in 1900. The goals were to form a separate graduate institution for the entire university not just one Department, and to promote scholarship based on sound research as the requirement for promotion of faculty. The Junior Research Club was formed in 1902. Sadly, both organizations refused to admit women. The Women’s Research Club was established later that same year as there were female researchers throughout the university, particularly in the Medical Department.

In 1901 the Regents were presented with a plan for creating a separate graduate department or division that would represent the university as a whole—in recognition that graduate work is of crucial interest to the entire university. The proposal was centered on a nine member council that would in turn elect a dean of graduate studies. This was rejected by the Regents, and rejected twice more in the course of the decade. The disputes delaying the formal establishment of a graduate department at U-M were not based on the value accorded to research or to educational theories. Only the Department of Literature, Science and Arts had created a Graduate Department, but the Departments of Engineering, Law, and Medicine, Dentistry and Pharmacy all had students engaged in post-baccalaureate studies. Faculty in Literature, Science and Arts did not want to relinquish their institutional hold on graduate education and they influenced the U-M community.

Yet by 1907 their Graduate Council was too cumbersome with 55 members, so they created an Administrative Council for graduate studies. Eleven members of the LSA faculty were appointed by the President for staggered terms in an effort to make administration more manageable. Even so, the very next year President Angell appeared before the Board of Regents to emphasize the expanding presence of graduate work at the University and warn that U-M would soon lag behind other universities if the Regents didn’t address the need for a university-wide graduate department.

The recognition of the imperative to provide funding for graduate studies grew at the same time. For example, although for many years Isaac Demmon, the head of the Department of English, had argued vigorously against using fellowships to support graduate students, during his chairmanship of the Graduate Council at the close of the decade he radically changed course. With the support of other faculty he convinced the Board of Regents to designate a substantial portion of the general fund to be used for fellowships. There was a growing trend, too, for the provision of gift funds for the support of fellowship from both individuals and also from corporations such as U.S. Rubber Company.

1910s

Thirty-two departments at U-M were offering graduate instruction by 1910 and there was an increasing demand for a new institution dedicated to graduate studies that would appropriately serve the interests of the university as a whole. This resulted in 1911 in the formation of a committee to study the issues which was chaired by the University President and consisted of three Regents, two deans, and two distinguished faculty members. Once again, the outcome was a recommendation to the Board of Regents that they authorize the establishment of a separate institution to administer graduate education at U-M. The Regents finally approved this in December.

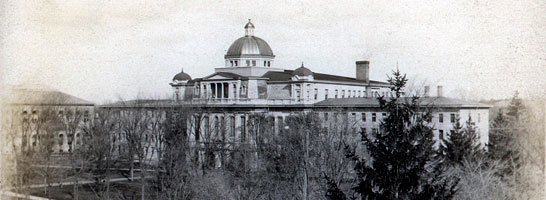

University Hall ca. 1906

The Graduate Department began operations in 1912, working out of offices in University Hall. There were 326 graduate students enrolled including 95 women. The administration consisted of an Executive Board comprised of the President of the University, Dean of the Graduate Department and seven faculty members drawn from across the university’s Departments serving what would be staggered terms of seven years. Karl E. Guthe, Professor of Physics, was appointed as the first Dean.

From the outset the Graduate Department was designed to be independent of special interests among the faculty, Regents or any other group at U-M. The new Graduate Department was expected to have access to all the resources of the university including faculty. This independence was reinforced by the fact that its funding did not flow from the other Departments at U-M, but came from general appropriations.

Academic procession, 1912

At the same time that the Regents formally established the new Graduate Department, they recognized the need for significant funding for students; not all could afford the cost of advanced study and research. Because appropriations for ten new University fellowships occurred very late in 1910, not all were awarded. Yet the demand was clearly there for all were used the next year and in 1912 the Regents added five more University fellowships and created 10 State College Fellowships. And as the following decades would show, this was only the beginning of U-M’s very significant investment in graduate student study.

What was known as the Graduate Department when established soon became called the Graduate School in 1915 when the Regents decided that the U-M Departments providing what was termed professional education would be called Schools and the Departments granting undergraduate degrees would be known as Colleges.

Campus walkway, 1912

The third hallmark of the special nature of the Graduate School seen in these opening years, in addition to its independence of administration and resources to support advanced study, is its role as an incubator unit. That is, from its inception the Graduate School was understood to be the ideal institution at U-M to foster innovative efforts, free from the influence of any particular discipline or administrative unit. For example, in 1913 the Regents placed responsibility for the publications of the university under the aegis of the Graduate School. This was accompanied by a special appropriation for publications put in the hands of the Executive Board. Among the most significant early publications were the faculty bibliographies, compiled and issued annually, that served to promote and encourage research.

Regents 75th Anniversary, 1912

1920s

The wealth that was generated and circulated in the U.S. during this decade brought tremendous growth at U-M. This took the form of investment in human capital and the physical plant, both made possible through individuals’ gifts, funding from foundations and business, and ever-increasing state support. There was an accompanying postwar growth in graduate enrollment which doubled during in the first half of the decade—far exceeding any expansion in undergraduate enrollment—and totaled 1,091 in 1929. These factors, along with the existence of a Graduate School intended to nurture research across the university, contributed to the emergence of one of U-M’s distinctive characteristics, interdisciplinarity.

The Michigan Union Library was completed in 1925 following a gift from Mrs. Edward W. Pendleton of Detroit in memory of her husband. His library was also donated.

At the outset of this decade the Regents and President Burton successfully persuaded the state legislature to support the construction of seven new buildings, including a new physics laboratory, and to plan and purchase land for the expansion of the original campus. There was similar support for increasing the number of faculty; in 1919 they numbered 444 but just five years later there were 652 faculty members. There was an explosion in a third type of resource necessary to graduate education. Resource materials that would be used in research were purchased or donated or secured through scientific expeditions were brought back to campus. This included, for example, large collections of books and maps bought in Europe, the Clements’ early Americana, Greek papyri, and zoological collections.

Since the close of the nineteenth century, when the push to establish a graduate school at U-M began, University leaders had recognized the value of having one school or college that embraced all disciplines and could resist the pressures of intra- and interdepartmental interests for control over resources. While a plan developed by the Executive Board in 1921 envisioned the Graduate School establishing a research division within each department this worked against the interdisciplinary impulse that was already coming into play. The research bureaus and institutes proliferating on campus had difficulty accommodating investigation into topics of interest to faculty in two or more departments. By 1929 President Ruthven created the Division of Fine Arts, a “grouping of units and departments for the purpose of co-ordinating various allied activities.”

Excavation for new Physical Science building which was completed in 1924

The cost of research within and among disciplines was supported by the rapidly increasing financial resources available through the Graduate School as well as intra- and extramural channels. For example, industry was increasingly willing to sponsor research in the College of Engineering, and there were grants from the Carnegie Corporation and the Guggenheim Fund. In 1925 the Regents established a separate trust fund of $12,000 at the Graduate School for research, primarily made possible through gifts provided by friends of the university. By the end of the decade this was increased to $22,000 to support publications in addition to another $30,000 to sponsor research. At the beginning of the twentieth century, a little over $1,000 had been received from outside sources for research; by end of this decade it totaled some $1.25 million.

An aerial view of the University taken in 1929, looking down on State Street

In 1920, Alfred Lloyd, Dean of the Graduate School, had written in his report to the President that “the future policy of the [Graduate] School, whatever the opposition or difficulty, must be persistently one of catholicity of interest and of loyalty to humanistic as well as to scientific studies, to pure science as well as to applied science, and, above all, to public interest and to independence of training and research.” A decade later the university had the funds and the administrative organization to make this a reality.

This was the location of the Engineering shops until it became the West Engineering Annex in 1923

1930s

During the Depression years, when higher education increasingly was beyond the reach of most Americans, there was remarkable development in graduate education at the University of Michigan. In part this was due to an astounding gift from one family. It also was the result of innovative scholars and academic leadership who seized the opportunity to pursue research and scholarship unhindered by narrow disciplinary boundaries.

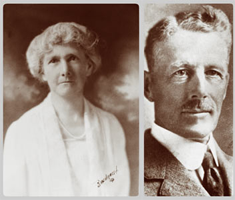

Mary and Horace Rackham

The University’s Graduate School bears the name of the lawyer who assisted Henry Ford with the incorporation of his business in 1903. Horace H. Rackham had the foresight to invest in Ford’s vision. Within a decade he and his wife were prominent philanthropists and higher education a major beneficiary of their generosity.

In 1935 the Horace H. Rackham and Mary A. Rackham Fund of Detroit gave the University 6.5 million dollars: 2.5 million were to create a new building for the Graduate School and 4 million provided an endowment to support of scholarly investigations. As his widow, Mary Rackham gave another 1 million for research in the field of human adjustment. Gifts from the Rackham Trust eventually amounted to over 10 million dollars—the equivalent of 168 million dollars in 2011. The Rackham gifts and vision embodied the mission of the public research university and positioned the University of Michigan to take a national leadership role in the coming decades.

Façade of the Rackham Building under construction in 1936

The administrative structure of the Graduate School remained unchanged but this extraordinary gift was acknowledged by renaming it the Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies. During this decade the Rackham gift bore fruit in the creation of pre-doctoral and postdoctoral fellowships, support for faculty research projects, and the landmark building intentionally designed to provide ample private space for students and faculty to pursue their research as well as public space to nurture the intellectual and artistic life of the community.

Despite the continuing shadow of national economic hardship, the reality is that the Rackham gift was only one of a significant number of gifts in this decade that greatly increased access to graduate studies by providing financial support to students. By 1939-1940 there were some 148 scholarships made available through monies provided by industry, friends of the University, special endowments, and appropriations from general funds. Total enrollment at the Graduate School during the fall and winter terms that year was just over 3,000 with 1,203 degrees awarded in the spring.

One of the hallmark roles of the Rackham Graduate School really came to the fore during the course of this decade. Since the close of the nineteenth century, University leaders had recognized the value of having one school or college that embraced all disciplines and could resist the pressures of intra- and interdepartmental interests.

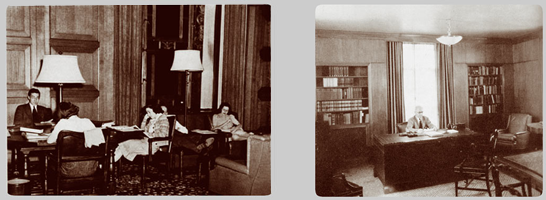

Rackham Study Lounge, ca. 1939 (left), and the Deans Office (right)

A striking number of innovative and interdisciplinary endeavors were established or placed under the aegis of the Graduate School in the 1930s. These include the Institute of Public and Social Administration, established in 1914; the University of Michigan Press, created in 1930; the Bureau of University Archives, created by the Regents in 1937; Fenton Community Center, established in 1938; the Center for Graduate Studies, opening in Detroit in 1939. Mary Rackham, through an additional gift of a million dollars, in 1937 established the Institute for Human Adjustment under the administration of the Graduate School. By 1940 the Institute included the Speech Clinic, Arthritis Research Fund, Psychological Clinic, and Sociological Research Unit.

1940s

In many ways the effects of the war that dominated this decade shaped the lineaments of the Graduate School. In 1940 the School had, thanks to the Rackham endowment, the exquisite building and impressive funds to support the pursuit of graduate education. By 1949 it exhibited the core features that distinguish the School at U-M: the Graduate School served national interests in the development of new knowledge; it was a primary incubator for new programs and fields of study; it provided a significant locus of financial support for student and faculty research.

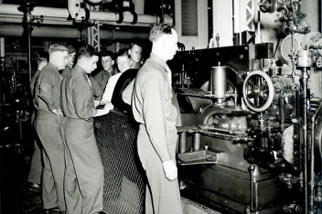

A demonstration in the mechanical engineering laboratory is being given to these members of the engineering unit of the Army Specialized Training at the University.

Group of Japanese language experts trained at University of Michigan.

Professor in classroom of students in uniform pointing to map of Southeast Asia.

Institute for Human Adjustment (renamed the Mary A. Rackham Institute on July 1, 2014); Dr. Wilma Donahue, March 1948, using Faximile visograph for experimental study.

The expected change was in enrollment. In September, 1940 the Burke-Wadsworth bill required compulsory military training of single men between 21 and 36. It allowed for deferment for enrolled college students until July 1, 1941 though students over 21 still had to register. Initially deferments were based on occupational shortages in fields such as chemistry and engineering. Of course, many students as well as faculty chose to enlist. After Pearl Harbor was attacked that December the decline in numbers accelerated. By 1943 graduate student enrollment had fallen to 633 from a total of 3,083 just four years prior.

The war had a marked effect on what was taught at U-M and who came here for instruction. Specialized training and research degree programs proliferated in engineering, chemistry, meteorology, foreign languages, civil administration, and other areas related to war needs. Much of the Rackham Building was turned over to student training in these fields and this took a heavy toll on the building itself.

The students and faculty who remained increasingly were involved in research supported by federal contracts. By April of 1942 the government awarded 31 research contracts to U-M, most of them classified. Though the advanced research in many fields was driven by the war, it resulted not only in effective weaponry but also in outcomes such as the influenza vaccine and a long-wearing fabric highly resistant to cold and water. The war precipitated a flood of funding from the federal government and corporate sector that would continue over the next two decades.

The end of the war did not bring a return to the status quo for the Graduate School. True, the graduate students returned as expected—3,125 that first year. And the building received extensive redecoration after the heavy use by military units. At the same time, the Graduate School building, and the people who worked there, continued to nurture the growth of new interdisciplinary projects. Here are a few examples. The Center for Japanese Studies was established in 1947 with funding from the Carnegie Foundation and Rackham, and initially was under the auspices of the Graduate School. The Regents established the Statistical Research Laboratory in 1947 under supervision of the Executive Board of the Graduate School and operations were housed in the Rackham Building. So, too, was the Survey Research Center, supported by government agencies and industries with a need to know public attitudes to both politics and services, and joined a year later by the Research Center for Group Dynamics.

In addition to becoming the focus of interdisciplinary endeavors, the Graduate School became responsible for oversight of funding that supported the rapidly expanding research efforts of both graduate students and faculty. Funding for these proliferating opportunities derived from a range of public and private sources. There were contracts with businesses and with the multiplying federal agencies; there were grants from foundations and endowments from families. The University’s Committee on Budget Administration recognized the need for centralized oversight and in 1947-48 determined that all budgets supporting research and fellowships should be administered through the Graduate School.

1950s

International conflict continued to have a significant influence on graduate education at the U-M in this decade, just as it had in the preceding ten years. As the Second World War gave way to the Korean War and then the Cold War, our campus saw both a familiar fluctuation in enrollment and an even more intensified engagement in research and amount of funding available for research. The rapid expansion of interdisciplinary fields, a hallmark of the University by mid-century, allowed us to compete on a global as well as a national scale. Because Rackham provided oversight for graduate programs and was not part of another office, school or college, it took on the responsibility for managing research funding for the entire University.

Nuclear engineering students attend class at the Ford Nuclear Reactor.

When the Korean War ended in 1953, graduate enrollment leapt to 4,042. Rackham was third among the nation’s graduate schools in the number of master’s degrees conferred (1,423), and seventh in the number of doctorates (265) that year. However, rising enrollment and demand for larger faculty resulted in 20% of instructors being Teaching Fellows (ABDs) by 1957. Political and labor movements emerging in the U.S. two decades earlier made their mark of our campus. For example, in 1954 graduate students formed their own organization, the Graduate Student Council (later known as the Rackham Student Government). That same year, three U-M professors were called before the House Subcommittee on Un-American activities, refused to answer some questions, and were suspended by President Hatcher.

Magnetic spectrograph. Dr. Donald Glazer, physics instructor, in charge. March, 1951

The Graduate School continued to serve as an incubator for innovative projects. Many had their beginning when they were housed in and partially supported by Rackham. These included, Gerontology Research, Michigan Historical Collections, the Linguistic Atlas, and the English Language Institute. The Research Laboratory installed an IBM 650 computer in 1955 and the explosive demand for computing services resulted in a new division of the Statistical Research Laboratory, called the Computing Center, created in 1959. Between 1955-1958 12 new doctoral programs in interdepartmental efforts: Aeronautics and Astronautics, Engineering Materials, Nuclear Science, Social Work and Social Science, American Culture, Communication Sciences, Far Eastern Studies, and Industrial Health were among the new graduate degree programs.

Alex Veliko (computer operator), Bruce Arden (research associate) and Bernard Galler (assistant professor of math) at work with the printer that transcribed computer results from tape to paper.

The American response to the launching of Sputnik in 1957 spurred the most notable expansion of scientific and engineering fields, markedly expanding defense-oriented research. This was accompanied by a parallel influx of monies that supported student researchers through the projects. Over the next decade the availability of funding helped to double enrollment and number of doctorates awarded. It’s significant that the Graduate School did not choose to withdraw support for social sciences and humanities. Rather, the Executive Board distributed the bulk of its quarter million in General Funds and Rackham monies to students and research in these fields in effort to preserve the excellent programs in which U-M held national prominence.

By the close of this decade the amount of financial support for research ran to the millions of dollars and University leadership saw the Graduate School as the logical and most suitable place in which to establish the Office of Research Administration. Ralph Sawyer, Dean of Rackham, was appointed as the University’s first Vice President for Research while simultaneously remaining Dean as the roles had parallel missions. Of course, having dedicated leadership and staff for this office served in turn to facilitate successful grant-seeking from federal and corporate concerns.

1960s

This is a decade known to Americans as a time of radical social change. Yet the focus in public memory on emerging civil rights, Johnson’s Great Society, and then the war in Viet Nam can distract from the realities of continuing intensive corporate and federal investment in advanced research. This is evident in the funding available for research and new fields of study at U-M. Early in the decade there were 220 research projects for industry on campus in addition to a flood of government contracts and foundation grants. And Rackham was the center of activity for it all. More important, perhaps, than campus unrest for the history of graduate education at U-M are the underlying institutional changes that positioned Rackham to address social needs.

Chihiro Kikuchi, professor of nuclear engineering, with graduate student in the mid 1960s.

The expansion of research contracts and new interdisciplinary programs that had begun after the war continued to accelerate at U-M. Not surprisingly, the development of new areas of graduate study continued to mirror national interests. For example, new programs within the Rackham family included Computer, Information and Control Engineering, Bioengineering, Toxicology, Natural Resources Economics, Public Health Administration, Social Work and Political Science, Water Resources Engineering, Ecology, and Urban and Regional Planning. Graduate study at U-M expanded not only to new fields but also new locations: a program in Mechanical Engineering was initiated on Michigan’s Dearborn campus. Despite size of enrollment and number of graduate degree programs, Michigan remained as always in the national forefront when it came to offering excellent graduate education. A study by the American Council on Education in 1969 rated U-M’s graduate degree programs within the top ten and often within the top five out of all in the country.

In front of the Rackham Building during U-M sesquicentennial events, 1967.

Other facets of institutional change at the Graduate School during the 1960s resulted in practices considered long the norm at U-M by the end of the century. Some changes turned the degree-earning process into the familiar model we have now. Such was the Executive Board’s decision in 1966 to use the term Candidate in Philosophy to indicate those who had passed a comprehensive exam and completed all requirements except submission of a doctoral dissertation. The following year language requirements were modified so that departments could set their own guidelines and opt not to require a reading knowledge of French and German.

Campus protest in the late 1960s looking across the Diag toward Rackham.

A far more significant change took place in the policies determining the nature and use of the Rackham endowment. By a vote of the Rackham Board of Governors in 1964, the separate funds making up the Rackham endowment were joined into one. At the same time the Board determined that the Rackham Dean and Executive Board each year would decide how to use the annual allocations for graduate fellowships, faculty research grants and faculty subventions for publication. As a result of these changes, there was an astounding growth in the distribution of pre-doctoral fellowships: in 1961 there were 836 awarded and by 1967 there were 4,106 awarded.

Demonstration in support of 150 black students in sit-in at the Administration Building, April 1968.

Similarly, in 1967 these changes to the Rackham endowment resulted in the initiative known as the Opportunity Program. This focused on funding designated specifically for minority students with the goal of increasing their numbers among the graduate students. In only a few short years the demands for access to higher education and the efforts to institute rapid advances in diversifying U-M exploded on this campus.

1970s

These were the years when Michigan truly earned its reputation for dissent in the service of social justice and societal change. While the student protests gained national attention, of more significance in the long term are the responses on the part of U-M and the Graduate School that resulted in immediate, long-term changes in graduate education and culture of graduate school. By the end of the 1970s, national economic decline resulted in a substantial cut in the financial support for graduate education; this required the leadership at Rackham to respond creatively while still maintaining the value of equal access to higher education and the opportunities it brings.

Center for the Continuing Education of Women scholarship winners, 1971

During the second half of the 1960s there was increasing campus unrest as faculty, graduate and undergraduate students expressed their frustration over the underrepresentation of minorities in every sector of the campus community. Students formed the Black Action Movement (BAM) and in 1970 they led a campus-wide strike, demanding that the university provide whatever funding was needed to increase the percentage of blacks on campus. Rackham responded by creating an Office of Graduate Minority Affairs in 1971 which in turn was responsible for implementing recommendations for recruiting and other services. Rackham also rapidly expanded the existing Opportunity Program and it quickly became one of the largest of its kind in the country. This program worked in conjunction with departments to select suitable faculty, allocate funding, and provide other means of support. By 1975 the percentage of doctoral degrees awarded to African Americans increased to 9.8%.

GEO rally 1970s

In 1960 11% of graduate students were women and a decade later that had almost doubled. Yet greater numbers did not result in equal treatment. In 1970 a group of women at U-M filed a complaint with U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare against the university. This cited inequality of opportunity in applications for admission, funding, salaries and a host of other areas. As a result, the government withheld federal grant money during investigation and the university created the Commission for Women that same year. This commission went on to uncover the extent of the problem in the Graduate School. Men were far more likely to receive the best research funding, women were discouraged from many fields, particularly in STEM. As a result of these and many other findings graduate departments were obliged to set affirmative action goals and processes to meet them. Rackham’s Dean Donald Stokes formed a panel in 1972 to consider the status of women and to recommend steps to consider guaranteeing equal access to graduate education. In 1974, the Committee on the Status of Women in Graduate Study and Later Careers issued a report, The Higher, the Fewer. As a result of the findings, the Board of Governors established a new fellowship program for nontraditional students.

Earth Day demonstration, 1970

These rapid changes occurred in the context of abrupt economic downturn. Nationally, problems such as the oil embargo, inflation, and reduced federal funding disrupted both the general fund and research budgets. When U-M announced a 24% increase in tuition in 1973, with no increase in Teaching Fellow salaries, graduate students intensified their efforts to organize a union. The next year they successfully voted to form the Graduate Employees Organization (GEO). Eventually they emerged with a contract that had a 10% tuition waiver, and a stipulation that future contracts would be applied without regard to non-relevant factors such as sex, race, creed, color, religion, national origin, age, handicap, or sexual preference.

The struggling job market resulted in the need to find jobs in the non-academic arena. During the second half of the 1970s Rackham took leadership on numerous fronts. For example, Rackham sponsored the Conference on Alternative Careers for Ph.D.s in the Humanities and Social Sciences; initiated a study of Ph.D. employment, supported by a grant from the U.S. Department of Labor; established the Ph.D. Review Committee to determine how to evaluate the quality of programs and suggest the future direction of graduate education; convened an international conference on the future of graduate education, supported by the NEH; hosted a conference with the National Association of Manufacturers to explore common interests and problems in industry and the university; joined General Motors in sponsoring a Conference on Business Careers for Ph.D.s in the Humanities.

1980s

The economic troubles of the prior decade extended into this one. Declining state support for higher education, inflation, and federal regulations continued to take a toll on education in the state of Michigan. In fact, in 1982 the state of Michigan ranked 50th in terms of the growth rate for the support of higher education. One outcome was that U-M no longer was a truly public university as private funds were required to support the majority of operations. Another was that for access to graduate education grants and fellowships were increasingly essential.

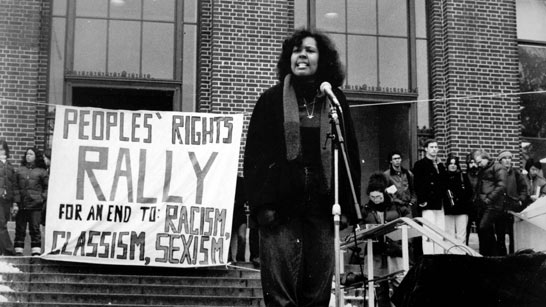

People’s Rights Rally on the Diag, 1981

Rackham leadership was at the forefront of the national fight against federal budget cutbacks of loan and fellowship funds that seriously jeopardized the future of graduate education and at the same time sought to increase resources for students on campus. For example, The One Term Fellowship was created, giving a term of support to students who were able to complete their dissertations within that span of time. Similar recognition was given to the need to support faculty research. The Faculty Fellowship Enhancement Award program was created by Rackham and OVPR with the purpose of providing modest grants to faculty who have been awarded prestigious national fellowships in the hope that more U-M faculty would apply for such fellowships.

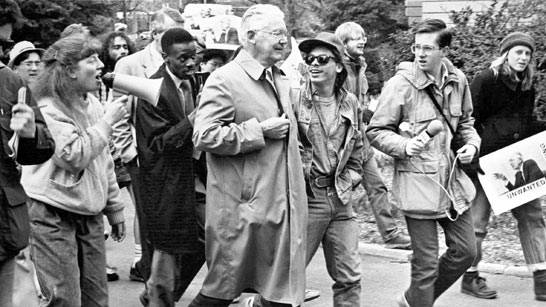

President Fleming and demonstrators, 1988

The challenges to the access of women and minorities to higher education endured. Although 9.8 percent of Rackham doctorate degrees had been awarded to African Americans in 1975, by 1987 that number had plummeted to 4.6 percent. The Graduate School responded with innovation. The Rackham Merit Fellowship (RMF) was created in 1983 as a multi-year funding package for students historically underrepresented in graduate education. To increase the potential pipeline of applicants, the Summer Research Opportunity Program (SROP) was offered to promising minority undergraduate students. The first Summer Institute was in 1989, providing the opportunity for an accelerated introduction to graduate school to all incoming RMF recipients.

Pushed by the student strike in 1987 known as Black Action Movement (BAM) III, the administration negotiated with students. The outcome was a six point action plan that set the foundation for what became known as the Michigan Mandate. Its strategies for increasing diversity on campus coupled academic excellence with social diversity and fell under four rubrics: student recruitment, achievement and outreach; improving the environment for diversity; faculty recruitment and development; staff recruitment and development. As a result of the Rackham initiatives stemming from the Michigan Mandate, for the period of 1986 to 1992, successful candidacy for students of color rose to 73 percent (candidacy for white students was 70 percent during this same period).

The energy and resources devoted by Rackham during this time did not come at the expense of its multifaceted mission. In 1981 Rackham held the first grant competition for research opportunities for U-M faculty members in the People’s Republic of China. The Wallenberg Endowment was established at Rackham in 1985 to commemorate Raoul Wallenberg and to recognize annually those whose own courageous actions echo his extraordinary values and achievements. The interdisciplinary Institute for the Humanities was developed by Rackham in 1987. In the fall of 1988 Rackham aptly honored the 50th anniversary of the building’s construction with a national symposium on “Intellectual History and Academic Culture at the University of Michigan.” The key role played by the Graduate School at U-M is reflected in the move in 1984 to expand the Dean’s role with the additional designation of Vice Provost for Academic Affairs.

1990s

The poor economy and rapidly dwindling state support for higher education through the prior two decades took a toll on research universities. Nonetheless, the Rackham Graduate School remained one of largest at any research university in the U.S. with a notable number and variety of programs in every field of learning. And the number who graduated each year remained high. For example, during the academic year 1990-91, there were 652 doctoral and 1,560 master’s degrees awarded. Rackham was able to remain in the forefront as a result of innovations that prepared students for the challenges of the next century as this one drew to a close.

A longtime friend and colleague of Raoul Wallenberg, Ambassador Per Anger (seated in front of a portrait of Raoul Wallenberg) worked closely with him in Budapest to save the lives of thousands of Hungarian Jews. He received the Wallenberg Award in 1995.

Nancy Cantor became the first woman to be selected as Dean of the Rackham Graduate School in 1996.

Earl Lewis, professor of history and of Afroamerican and African Studies, was appointed the eleventh dean of the Graduate School in 1999.

Obstacles faced by women and underrepresented group were slowly being removed, in part because of Rackham’s forceful engagement with the values behind the Michigan Mandate, the university’s strategic plan created in the prior decade. Equal access to the highest levels of training and study depended in a large part on making the financial resources available for those without the means. One of the significant ways in which this was achieved was by awarding fellowships to historically underrepresented groups. By fall of 1991, Rackham provided 625 fellowships for academically talented students in these groups; this was an increase of 86 percent compared to 1987. Another way to ensure equitable distribution of funding was through teaching assistantships. By the early years of this decade, when women represented about 40 percent of all graduate students, women held approximately the same proportion of these assistantships as men. And this was the decade when first there was a female Dean, Nancy Cantor, professor of psychology, as well as the first African-American to be Dean of the Graduate School, Earl Lewis.

Rackham’s leadership engaged in a concentrated effort to secure additional funding for graduate students through grants from private foundations and federal sponsors, then amplifying the value of those awards with matching funds from the Rackham endowment. In 1991, the Mellon Foundation selected Rackham for participation in their Graduate Education Initiative. This had the goal of reducing student financial burden and attrition rates. At that time it was the largest effort ever undertaken by a private funder to support graduate training in the humanities. To expand the impact of the Mellon Fellowships, the Graduate School created Dean’s Fellowships to provide similar support to a set of programs in the arts and humanities. Similarly, Rackham continued to partner in successful proposals to the NSF’s highly competitive Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship Program (IGERT). The scarcity of minorities in the sciences and academia became the focus of federal efforts to ensure that the future workforce in the sciences was diverse. In 1998 the Graduate School successfully applied to the NSF with a consortium of other Michigan research universities for a grant from the Alliance for Graduate Education and the Professoriate (AGEP). Rackham received six million dollars to develop innovative models for recruiting, mentoring, and retaining minority students in science and engineering doctoral programs.

Innovations by the Rackham administration and the quality of its programs are seen especially in the prominence of interdisciplinary studies available in U-M graduate programs. Rackham provided both the financial and administrative support required for a culture of interdisciplinarity to flourish. In 1995 Rackham’s personnel structure was changed to provide an associate dean for each of the four divisions into which Rackham groups the academic disciplines. This encouraged work within the divisions and across disciplines. The Graduate School encouraged flexibility by creating innovative certificate programs which allowed graduate students to receive credit for specialized coursework outside their home disciplines in a wide range of topics. This decade saw development of the International Institute with its area studies centers, the Rackham Interdisciplinary Seminars, the annual Summer Interdisciplinary Institute, and the Rackham Interdisciplinary Workshops created and lead by students.

2000 and Beyond

At the opening of a new century, the Rackham Graduate School demonstrated an ongoing commitment to the core Michigan values of the past century while continuously improving the quality of graduate education in a rapidly changing world of new knowledge and new technology. This decade opened with the decision to renovate the building, saw redoubled effort devoted to ensuring equal access to higher education, and by the decade’s end the Graduate School had developed new services and projects dedicated to the success of graduate students at our university.

Graduate students elected to the Bouchet Honor Society in 2009 were (left to right): Joy Oguntebi, Jonathan Madison, Krystal Williams, Flannery Stevens, Reginald Rogers, RaShonda Flint, Kristine Molisa, and Haijing Dai.

In 2000 building renovations began in earnest with the financial support of the central administration. In the following year operations moved off campus to the Argus Building while the historic structure was closed and experienced a two-year makeover. Many of the public spaces were returned to their original style and splendor; equally important were much-needed infrastructure improvements. The initial décor and character were preserved or recreated wherever possible while at the same time twenty-first century technology for multimedia instruction was incorporated in the improved use of space. When the building reopened in 2003 the second floor study halls and library returned to student use. The magnificent Auditorium on the main floor, and the Amphitheatre and conference rooms on the fourth floor, returned to almost constant use for student events, performances, lectures and conferences.

Participants in the 2007 Summer Research Opportunity Program.

The Graduate School was an active participant in many national initiatives to improve graduate education. From 2001-2005, Michigan participated in the five-year Carnegie Initiative on the Doctorate (CID) which aimed to support, document and analyze innovations in doctoral education at leading programs. In 2001, Rackham joined the Responsive PhD project sponsored by the Woodrow Wilson Foundation. In 2004, the Graduate School became one of the original research partners in the Council of Graduate Schools (CGS)’s Ph.D. Completion Project, a research program working to understand graduate student retention and completion rates. In 2004 Rackham received $6 million from NSF for a collaboration with three other Michigan universities to encourage underrepresented minority students to enter doctoral programs in science and engineering (AGEP). The Mellon Foundation continued to support Rackham initiatives in the humanities, including targeted recruiting activities, Michigan Society of Fellows, and postdoctoral opportunities at Kalamazoo and Oberlin Colleges. Michigan is one of the largest recipients of NSF IGERT grants.

The university as a whole remained in the public eye through much of the decade as a battleground for the value of diversity in higher education and access to higher education for all in the U.S. Two lawsuits filed in 1997 challenged the university’s right to use race as a factor in admissions policies and they were joined as they made their way to the Supreme Court. Just as in the prior three decades, the Graduate School, along with all the other schools and colleges at U-M, engaged in promoting the value of diversity before and after the Court’s decision in 2003 that race can be a factor in some circumstances in admissions decisions. Rackham leadership and staff intensified their efforts to understand discrepancies in admissions and completion rates, and to develop modes of eliminating them. In 2006 voters in Michigan passed Proposal 2, amending the Michigan Constitution to ban public institutions from discriminating against or giving preferential treatment to groups or individuals based on their race, gender, color, ethnicity, or national origin in public education, public employment, or public contracting. The Graduate School met the challenge with significant changes in qualifying criteria for Rackham Merit Fellowships. Funding was reallocated to students who experienced financial hardship, were first generation college graduates, first generation citizens, or who came from an educational, cultural or geographic background that is underrepresented in graduate study in their disciplines.

Throughout course of this decade Rackham developed programs and resources to facilitate the success of all graduate students, no matter their backgrounds. In 2006 Dean Weiss initiated the Rackham Program Review. The Rackham deans meet once every four years with the leadership of the graduate degree programs to discuss successes and strategize ways to improve outcomes. That same year she opened a new office within the Graduate School, Graduate Student Success, offering a continuum of services from recruitment through placement. At the same time, the Dean sponsored other initiatives that involved faculty but worked toward the same goal: improving the graduate student experience and facilitating student success. Rackham also expanded the funding available to students for conference travel and research, and moved to the electronic submission of dissertations.

At the beginning of this new millennium the Graduate School at U-M had a far different role at the university than it had when it began to form in the early years of the 1900s. The sheer scale of the fundamental operation is notable: in 2009-2010, there were 789 doctoral degrees and 1,901 master’s degrees awarded.