Harms Report for the Detroit Reparations Task Force: Executive Summary

Introduction

In August 2023, the Detroit Reparations Task Force established a partnership with researchers at the University of Michigan (U-M) to develop a harms report that will inform the final recommendations the Task Force makes to the Detroit City Council. These U-M partners include the Center for Social Solutions, Poverty Solutions, the Rackham Graduate School, and the Center for Equitable Family and Community Well-Being. The harms report aims to document the injustices and human rights violations experienced by Black Detroit residents, in order to establish a historical record of the city’s active role in perpetuating and sustaining these harms. By detailing these injustices, the report provides a foundation for understanding the extent and depth of harms in order to make a compelling case for reparations in the city of Detroit. The final report was completed and presented to the Task Force in August 2024.

The Task Force identified five key focus areas, establishing a scope of work to direct the U-M partners’ research efforts. These areas are: 1) housing, 2) policing, 3) quality of life, 4) education, and 5) economic development and economic insecurity. Beginning with housing, the report details how the city’s history of discriminatory housing and land use policies in the 20th century laid the foundation for enduring financial, social, and racial inequities that emerge across the other focus areas. The report highlights the compounding effects of housing segregation on Black Detroit communities wrought by over-policing, health disparities as a result of disparate environmental impacts, chronic underfunding and mismanagement of Detroit Public Schools Community District, as well as emergency management, austerity measures, unemployment and transit inequity.

U-M partners utilized a variety of research methods, including the identification and analysis of archival materials and census data, the synthesis of existing scholarship, and interviews with Detroit community members conducted at the request of the Task Force. A cross-disciplinary group of faculty also led project-based courses covering topics identified in the scope of work. During the winter 2024 semester, Rackham Graduate School offered a graduate course designed to connect students and faculty working on research for the harms report and to promote systemic understanding of the issues through crossdisciplinary exchange. The report utilizes and defines a set of key terms, which organize the histories of injustice in Detroit: redlining, white flight, urban renewal, and austerity measures. These terms emerge across all of the focus areas and are critical to connecting the longer histories of harm to contemporary disparities experienced by Black residents in the city of Detroit.

Housing

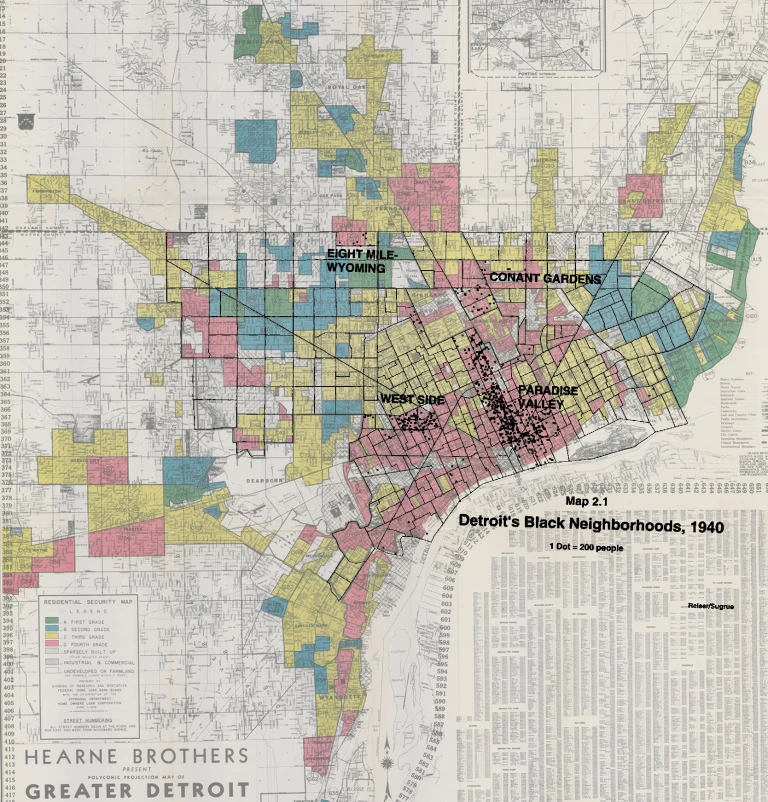

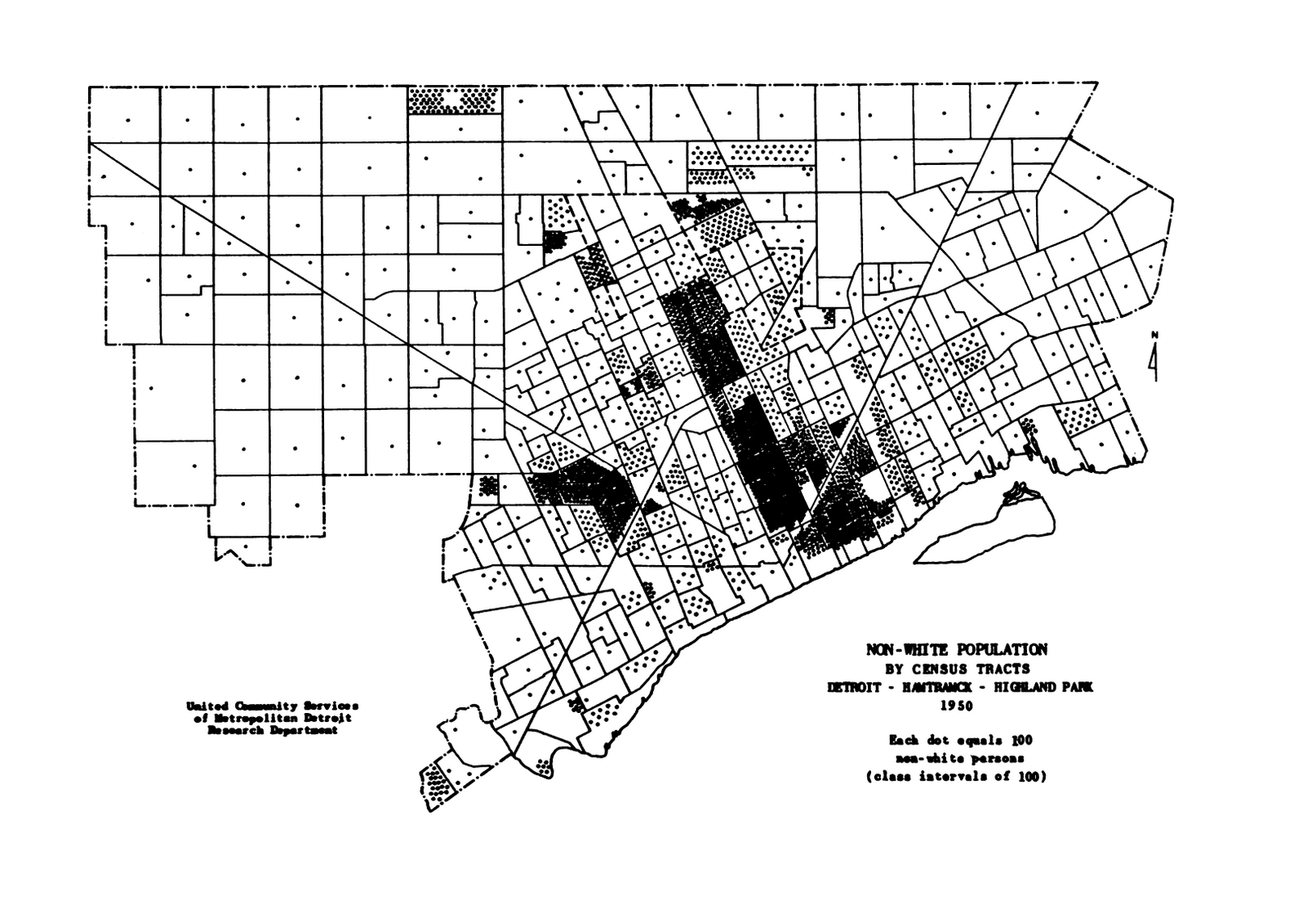

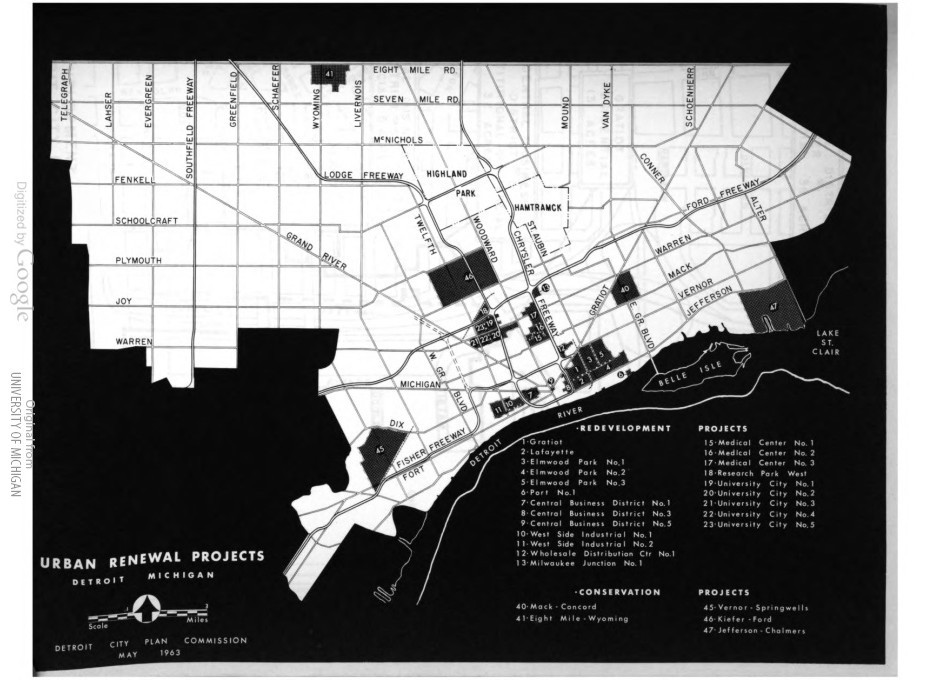

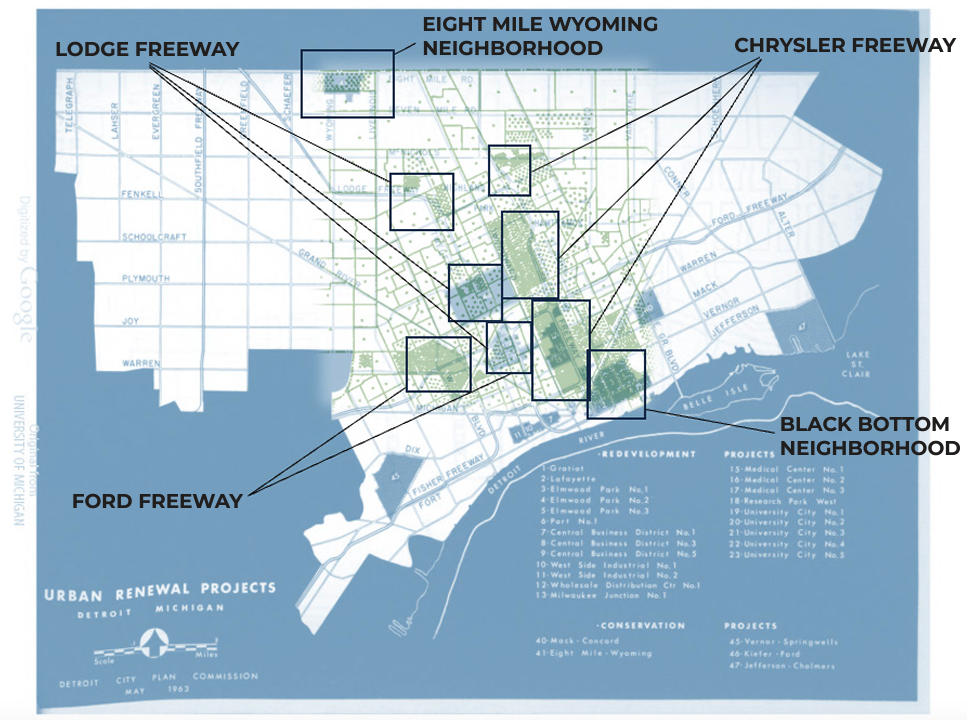

This section examines 20th-century housing and land use policies implemented and enforced by the City of Detroit. These policies, discriminatory in nature, solidified practices of segregation and displacement that disproportionately impacted Black Detroiters and laid the foundation for many of the social and financial inequities that still characterize the city today in housing and beyond. The policies and practices were enforced in their official capacity by city government officials and in their unofficial capacity through the violent resistance of white Detroit residents. Beginning in the early 20th century, housing segregation in the city was largely implemented by racially restrictive covenants that made it illegal to sell certain properties to non-white buyers. These covenants pushed most of Detroit’s burgeoning Black population into vibrant yet overcrowded neighborhoods like Black Bottom. Black Detroiters were then systematically excluded from suburban home ownership opportunities—the single largest generator of middle class wealth in the mid-20th century. Redlining policies denied Black homeowners mortgage loans in white-majority areas and designated Black-majority portions of the city “high-risk,” thus effectively devaluing their properties. At the same time, attempts to construct public housing for Black residents within Detroit were shut down by local government officials and white residents who rejected the idea of integrated housing in the city. Urban renewal and highway construction efforts led to the widespread destruction of Black cultural hubs like Black Bottom and Paradise Valley and displaced thousands of Black residents from those neighborhoods, a problem that the city failed to adequately address. Large scale out migration of white residents to the surrounding suburbs—a phenomenon widely known as white flight—led to widespread disinvestment in housing and infrastructure in the city of Detroit, an impact that is still being felt by the city’s majority Black population to this day.

Figure 1: Federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation “redlining” map for the Detroit area in 1939, which rated areas from “best” (blue) to “hazardous” (red), overlaid with the residences of Detroit’s Black population. Image by Paul Szewczyk from “Detroit Redlining Map” by Alex B. Hill, Dec. 10, 2014.

Figure 2: Map entitled “The Non-White Population of Metropolitan Detroit: The Number and Distribution of the Non-White Population in the Metropolitan Detroit Area: 1950 and Earlier Censal Years,” by the United Community Services of Metropolitan Detroit Research Department, 1955.

Figure 3: Detroit City Plan Commission map of federally-funded urban renewal projects between 1950-1963. Image held by University of Michigan from “Map: Detroit Urban Renewal Projects 1963” by Alex B. Hill, June 25, 2014.

Figure 4: Previous map of Detroit’s urban renewal project overlaid with the previous map of the residences of Detroit’s non-white population, with areas of Black displacement highlighted.

Housing and Land Use Numbers at a Glance

- 43,000: estimated number of houses and apartments built with racially restrictive covenants in Detroit before 1947

- 19,000: estimated number of Black Detroit veterans who did not receive GI Bill benefits like home loans

- 6,550: public housing units planned but not built in response to racial resistance from the City government and white residents

- 8,231: number of families displaced through federally-funded urban renewal programs between 1950-1966, with 67% being families of color.

“No housing project shall change the racial characteristics of a Neighborhood.” Segregationist policy adopted by the Detroit Housing Commission in 1943

Policing

This section examines the harmful relationship between law enforcement in Detroit and Black residents. The relationship can be characterized by three facets: 1) over-policing in the form of repressive, brutal, and often legal practices; 2) under-policing through the failure to protect Black Detroiters from crime or collective violence committed by white residents; and 3) the exclusion of the Black community from the design and implementation of policing policy, mainly through the historic exclusion of Black Detrioters from the Detroit Police Department force first as members and later as part of leadership. The report highlights the history of the Detroit Police Department as one of the deadliest police forces in the United States, with officers disproportionately murdering unarmed, Black civilians. In many cases, the officers involved in these murders have been shielded from accountability by the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office or internal DPD investigations that have ruled the officers’ actions “justifiable.”

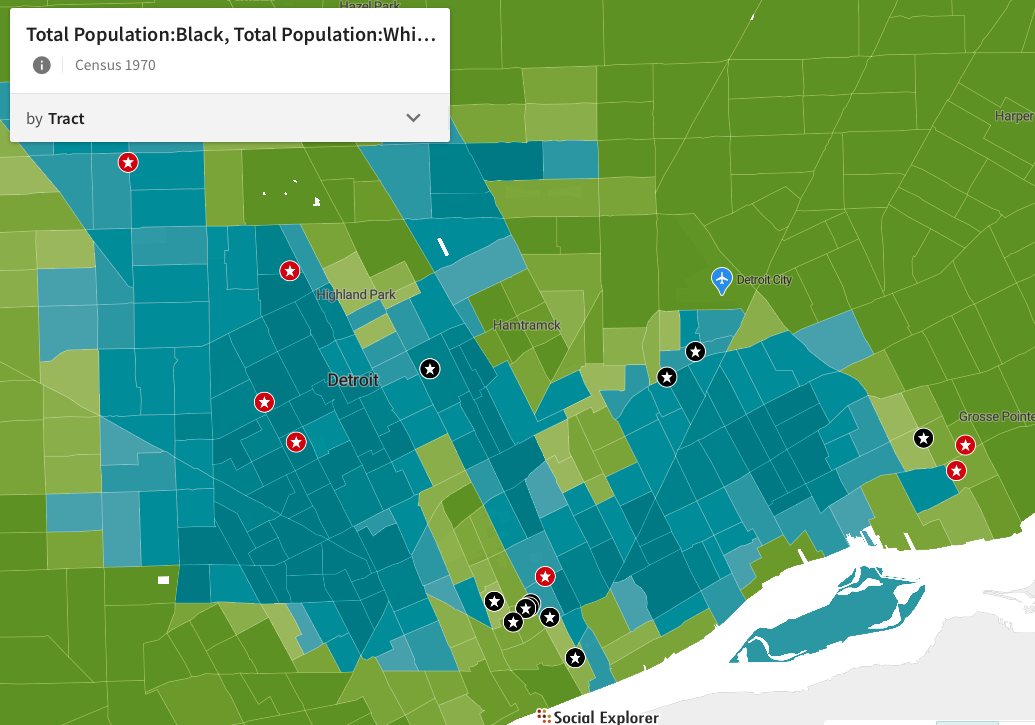

Figure 5: Map of location of 22 STRESS fatal shootings, showing concentration in the Cass Corridor/Midtown area and racially transitional areas on the East Side. Black dots = decoy unit shootings. Red dots = shootings by other STRESS units. Blue-shaded census tracts = predominantly Black population. Green-shaded census tracts = predominantly white population. Map courtesy of https://policing.umhistorylabs.lsa.umich.edu/s/detroitunderfire/page/rememberingstressvictims.

Policing Numbers at a Glance

- 35: number of Black officers in the 4,000-member Detroit Police Department in 1933, despite Black residents making up 7% of the city’s population

- 95: number of Black officers in the 2,591-member Detroit Police Department in 1963, despite Black residents making up 33% of the city’s population

- 1.4 million: number of secret political surveillance files compiled by the Detroit Police Department’s Red Squad in attempts to obstruct progressive groups from advancing racial equality and other causes between the 1950s and 1970s.

- 250: number of civilians killed by Detroit police officers between 1957-1973, with 79% of them Black or African American

“What white Americans have never fully understood–but what the Negro can never forget–is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it” – Kerner Commission, Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968

Quality of Life

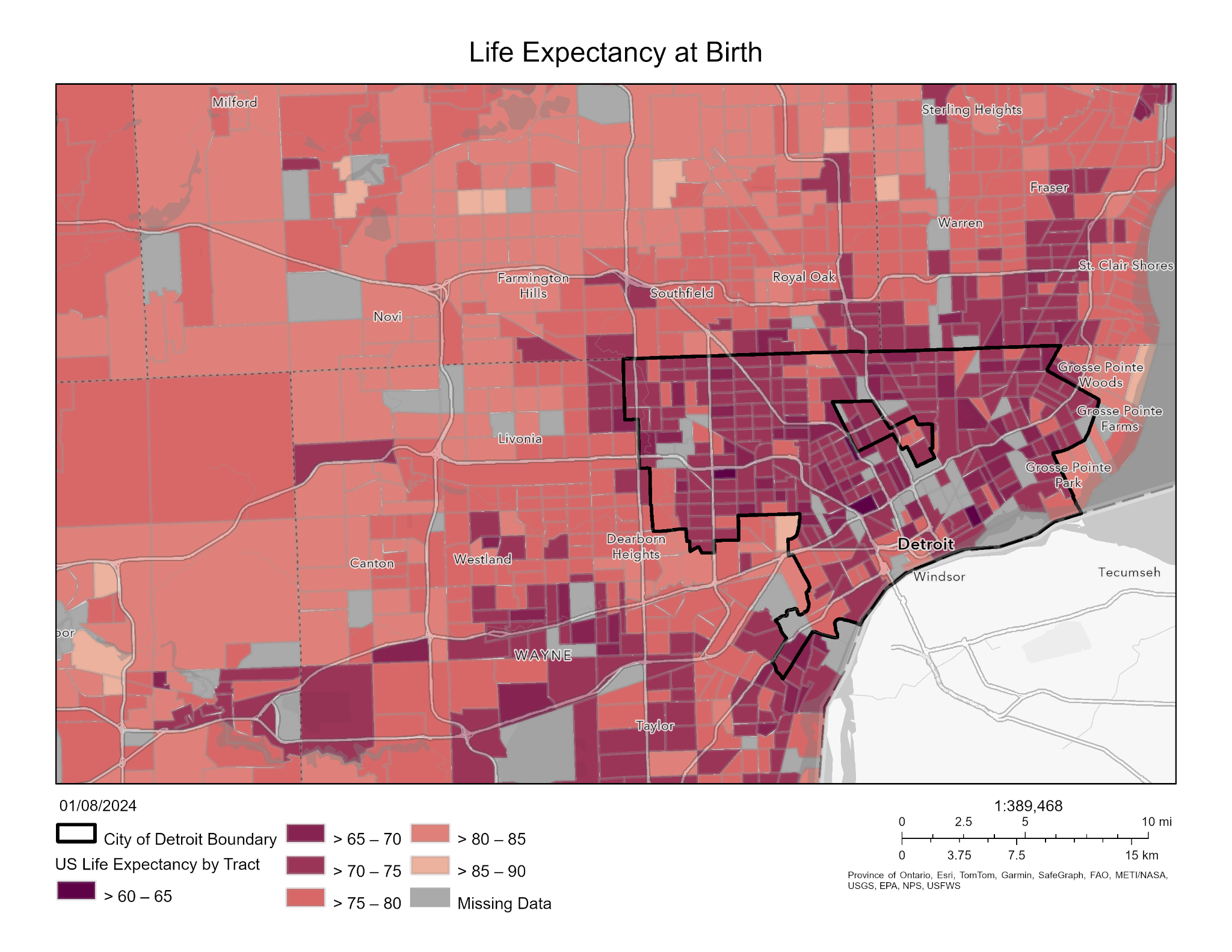

This section traces the history of health harms experienced by Black Detroit residents due to city and state policies. These harms have been compounded by decades of systemic racism, especially in relation to housing and public safety; they have resulted in significant health disparities in the city. Current and ongoing disparities in healthcare access for Black residents in the city are connected to policies that initially excluded Black Detroiters from accessing public health care services, as well as to the later disinvestment in and privatization of these services. In addition, redlining and other discriminatory housing policies relegated Black Detroit residents to areas of the city prone to flooding, poor air quality, and excessive heat and noise, environmental factors that increase the risk of poor health and disease. Human-caused climate change will only exacerbate the existing inequities. The compounding effects of housing, environmental and climate impacts, and health outcomes underscore the importance of the quality and resiliency of the city’s built infrastructure for Black communities. The current I-375 Reconnecting Communities Project is slated to replace I-375 with a surface-level boulevard. Despite its reparative intent, the project could exacerbate existing inequities of surrounding communities by increasing exposure to noise pollution and higher vehicle emissions.

Figure 6: Life expectancy at birth for Detroit and the surrounding areas. Data derived from CDC Life Expectancy Estimates for US Census Tracts over 2010-2015. Betzaida Tejada-Vera, Bastian B, Arias E, Escobedo LA., and Salant B., Life Expectancy Estimates by U.S. Census Tract, 2010-2015 [map], “National Center for Health Statistics Data Visualization Gallery”, last updated Mar. 9, 2020,

Quality of Life Numbers at a Glance

- 18: number of Black-owned and operated hospitals in Detroit before the passage of the 1965 Medicare and Medicaid Act, which forced white-run hospitals to desegregate

- 8: number of cancer-causing chemicals emitted by the Marathon oil refinery in Southwest Detroit

- 99th percentile: national ranking for prevalence of adults living with asthma for most of Detroit

- 70%: percentage of homes in Detroit that have reported issues with black mold

“There is a sprinkling of 3-flats throughout the area. All residences are near some industrial plant. All have R.R. and industrial smoke and soot. There is a general sprinkling of razed and boarded up structures… Sewage disposal plant is in the extreme southwest section of the area. Portland, Peterson and Copeland are negro streets. Age and type of area rate it 4th grade.” – The 1939 HOLC map description of a “red” area in Detroit judged to be undesirable for purposes of federal loans

Education

This section highlights the decline of Detroit Public Schools Community District (DPSCD) as a result of federal and state policies, economic disinvestment following white flight, and chronic underfunding and mismanagement. These factors have adversely affected Detroit students who experience lower graduation rates, are less prepared for postsecondary education, and record the highest rates of chronic absenteeism in the nation. DPSCD schools receive less funding on average than public schools in the surrounding suburbs. The demographics of these suburban areas are predominantly white compared to the predominantly Black demographics of DPSCD students. De facto racial segregation, driven primarily by white flight, has been solidified by cases like Milliken v. Bradley, which obstructed the ability of the federal government to integrate public schools. Inequities in funding and the imposition of austerity measures during the city’s era of emergency management have also led to the poor quality of facilities and resources that DPSCD schools are able to provide for their students. This further impacts educational quality for students and erodes trust between community members and the DPSCD administration.

Education Numbers at a Glance

- 17%: percentage of Detroit residents aged 25-34 who hold a bachelor’s degree, compared to 35% nationally

- Less than 50%: number of DPSCD buildings with air conditioning

- $1,973: amount more spent per student in the neighboring Grosse Pointe Public Schools as compared to DPSCD

- 68%: percentage of students considered chronically absent - missing at least 10% of classes - in the Detroit Public Schools Community District during the 2022-2023 school year

Economic Development and Economic Insecurity

This section intertwines Detroit’s economic precarity and the city’s history of industrial decline, systemic racism, and urban policies that have disproportionately harmed Black residents. Currently, unemployment rates in Detroit are nearly twice that of the state of Michigan, and the labor force participation rate in the city is the lowest among the most populated 100 U.S. cities. Inequities in economic opportunity can be traced to a long history of employment discrimination. Black workers were systematically excluded from roles in key industries that promised economic mobility and union benefits, often relegated to low skill and high risk jobs. Economic prosperity for Black residents was further dismantled by mid-20th-century urban renewal policies that greenlit the destruction of Black cultural and economic hubs, resulting in the displacement of thousands of residents. The implementation of austerity measures in the city led to significant reductions in public services, retiree benefits, and pensions, placing an undue financial burden on the city’s majority-Black population. Economic insecurity has been further perpetuated through the city’s lack of transportation infrastructure, which places an undue financial and time burden on Black Detroit residents and limits their economic mobility.

Economic Numbers at a Glance

- Over 300: Black-owned businesses in Black Bottom and Paradise Valley in 1942 before the neighborhoods were flattened during urban renewal

- 109: number of businesses leveled during the construction of the Lodge Freeway, many of which were in predominantly Black areas of Detroit

- 21,000: approximate number of retired City workers who faced retiree pension and health care cuts after the 2013 Detroit bankruptcy

- $69: per capita municipal spending on transit in Detroit, as compared to $119 in Atlanta and $471 in Seattle

A proposal that called for the demolish of an intact community “was called ‘blight by announcement.’ And that was a practice that was used … to prevent Black people from two things: getting loans to fix up their property because there was that cloud of uncertainty, and then the other piece was, well, what they did to us in Black Bottom, they’re going to be doing it up here, so we’re not going to fix our places up.” – Hilanius Phillips, former Detroit City Planner during project interview

Conclusion

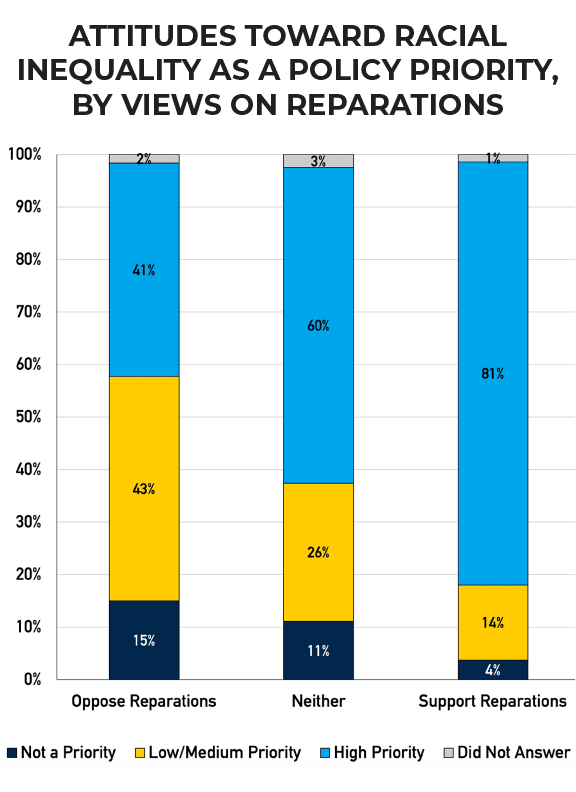

The report highlights the importance of understanding the full complexity and intertwined nature of harms to a reparative process. In the city of Detroit, 63% of residents surveyed support reparations. This figure stands in stark contrast to the 63% who oppose reparations at the national level. The strong support among Detroiters can be linked to the city’s high number of Black residents relative to the rest of the country, an awareness of widespread harm, and an understanding of how these harms have and continue to impact Black communities. This report provides readers with an understanding of the ways that historic municipal housing and land use policies created conditions that led to harms across the five key areas of focus: housing, policing, quality of life, education, and economic development and economic insecurity. The report offers some initial suggestions for how the Task Force might build on the foundation laid in these initial areas of focus through further research.

Figure 7: A graph showing that Detroiters’ attiudes about reparations largely track their attitudes about racial inequality. Erykah Benson and Jasmine Simington. “Collective Remembrance and Detroiters’ Views Toward Racial Inequity.” Detroit Metro Area Communities Study, March 2023.