Americans may be known worldwide for their broad toothy smiles, but the reality of access to dental care in the U.S. is anything but dazzling. According to the CareQuest Institute for Oral Health, nearly 70 million adults and nearly 8 million children in the U.S. have no dental insurance; many who do have coverage find it to be inadequate. The issue is exacerbated by the fact that American dentists make the bulk of their income from cosmetic procedures like veneers, limiting availability for individuals on Medicaid.

“It can be really difficult to get dental services, particularly for low-income folks. And we know that poor dental health leads to bad physical health and can really affect your income,” says Lucy Smith, a Rackham doctoral candidate in the history and women’s and gender studies departments. “We’re punishing people for having bodies, essentially.”

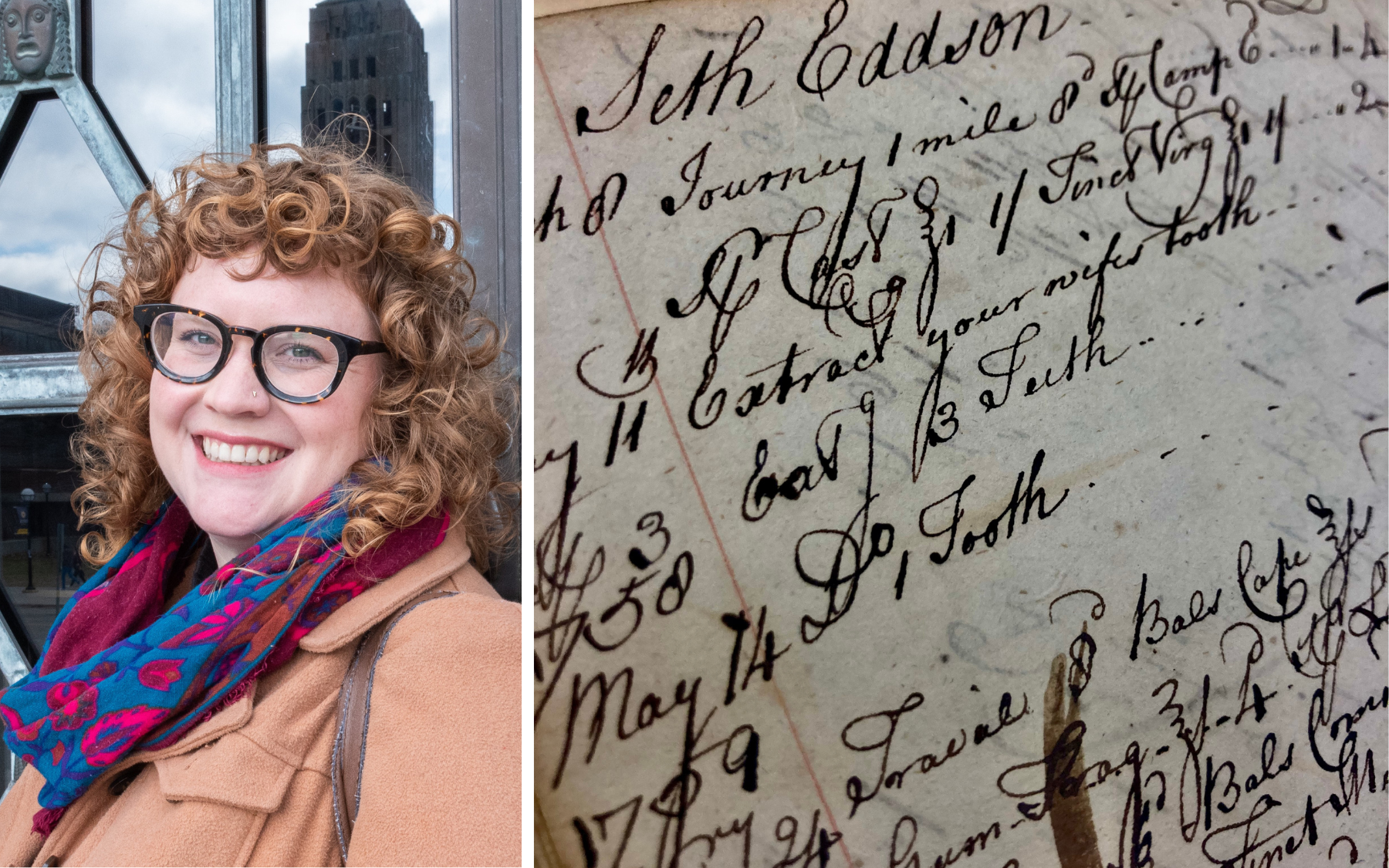

Smith studies the history of human teeth in early America with attention to how these histories inform our lives today. Over the past two years, Smith has traveled to 24 different cities to spend time combing through 38 archives to better understand America’s obsession with their pearly whites. She points to the prevalence of perfect teeth as not only an expectation for American leaders but as an internalized aesthetic with moral overtones for the entire population.

“Someone with missing teeth may have issues finding employment in our country—people assume that they’re morally bad. I’m interested in the time period when we start to associate having a good, clean, bright white smile with goodness of character, an American virtue,” Smith says.

Conducting research in a “fractured archive,” Lucy Smith has visited 38 archives in 24 different cities over the past two years. The image on the right depicts archival text from the Connecticut Museum of Culture and History. Smith reports that one challenge of her work has been deciphering thousands of pages of centuries-old handwriting in letters, ledgers, and account books.

The Dawn of Dentistry

According to Smith, prior to the 18th century—and even during much of it—dentistry was primarily limited to extractions performed by anyone with immense strength, fine motor skills, and effective tools. Typically, this work was done by metal workers, barbers, and blacksmiths—or even traveling “tooth pullers” who’d charge a ticket price for audiences to view the pain spectacle, often accompanied by jugglers and other performance artists.

Change started to come in the early 1700s, as demand for dental care surged alongside the introduction of tea, coffee, and sugar cane to European diets due to vast expansions of the transatlantic slave trade. At the same time, medical knowledge was expanding, leading dentists to experiment with tooth transplants and dentures. The teeth themselves came from a variety of sources, including those who had died on the battlefield.

“For a time, all human teeth for sale were called Waterloo Teeth, as they were taken from the dead from the Battle of Waterloo,” Smith says.

Teeth were also sold to dentists by the poor and were taken from enslaved people.

“Enslavers were considering the mouths of enslaved people in radically different ways than an elite young lady in Philadelphia,” Smith says. “We need to be cognizant of not only how different bodies were read during the time period but also how our positionality informs how we hear these stories today.”

An American Aesthetic

As dentistry evolved as a profession, the U.S. was in the process of becoming a nation and defining a uniquely American aesthetic for itself.

“I think we were trying to address a big question during this time period: ‘What does it mean to be—and to look like—a good American?’” Smith says.

Pointing to the consumer revolution of the 1700s, Smith notes that middle-class Americans had access to knock-offs of fancy fabrics usually reserved for society’s elites. This, coupled with the fact that newcomers to the country could be anybody—records were spotty, easily forged, and communication was slow—left American elites looking for ways to assert their status through bodily poise, posture, and polish.

“The way that you move your hands, the way that you smile, all of that starts to have these class connotations to them,” Smith says.

As class became coded by concrete physicalities in the United States and the transatlantic tooth trade became established with the rise of dentistry in Europe, a full set of straight, white teeth became part of the American visual aesthetic for the upper class.

Presidential Smiles

As the first U.S. president and a person who suffered from tooth decay and loss throughout his life, George Washington was acutely aware of America’s new aesthetic—and the importance of addressing it as part of his precedent-setting efforts.

“When George Washington took office at age 57, he only had one remaining tooth in his head,” Smith says.

His dentures at inauguration, created by dentist John Greenwood, were made with a hole on the bottom deck to slot over the one remaining tooth, which served as an anchor.

By his second year in office, Washington had lost his remaining tooth and used the power of his clenched jaws to keep in place a spring-loaded denture contraption made of lead, weighing a quarter of a pound, and bearing human teeth, as well as the teeth of domesticated animals and ivory.

“Nobody looked at Washington’s dentures in the 18th century and said, ‘Those are his teeth.’ They were clearly fake. But the important part in society at the time was the shared understanding of the performativity of what he was doing,” Smith says.

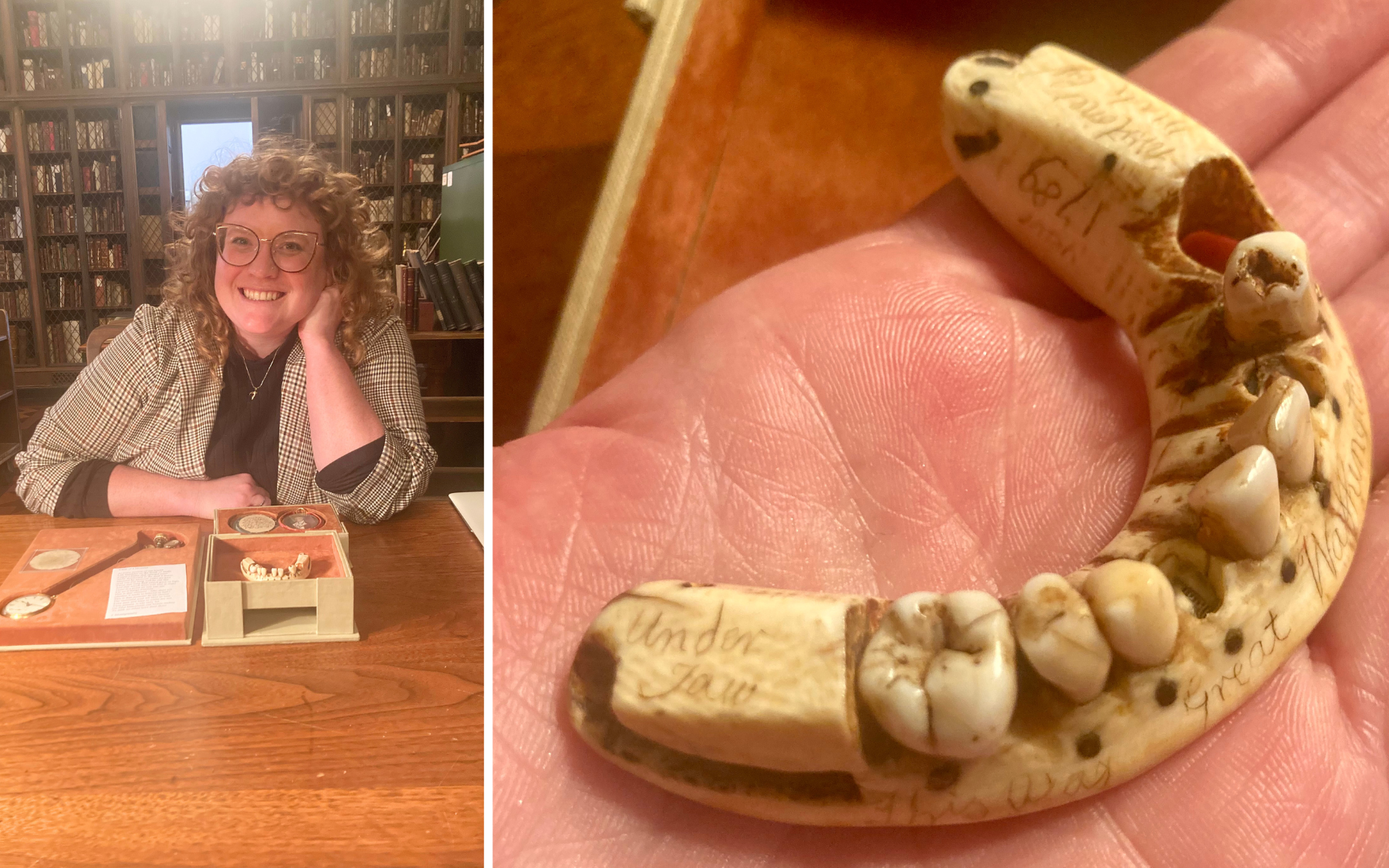

Lucy Smith in the archives of the New York Academy of Medicine, home to George Washington’s original dentures worn at the time of his inauguration.

Human Costs

The president wasn’t the only one wearing dentures—it was very common for elites to secure dentures, and teeth were imported and sold by the barrel.

“It’s common during this time period for people to be selling their teeth. If you open any 18th century newspaper, you’ll often see advertisements for dentists being like, ‘I will buy your teeth for two guineas,’” Smith says.

According to Smith, in 1784 the Bank of New York published the exchange rate of 1 British Guinea equating $4 U.S. dollars. Given that a male laborer made roughly 40 cents per day that year, selling a tooth would roughly equate to 20 days of work—a helpful amount during desperate times but certainly not substantive enough to pull anyone out of poverty or alter their socio-economic status.

Enslaved people in the United States during Washtington’s era often sold wares at local markets, including teeth. Official ledgers detail Washington’s purchase of nine teeth from unidentified enslaved persons at Mount Vernon, bought by Washtington on behalf of Jean Pierre Le Mayeur, a dentist who’d assisted him during the American Revolution. While it is unknown what became of the teeth, Smith notes that these particular teeth were not likely used in Washtington’s dentures.

“What we do know is that Washtington pays about half of what the market value would have been. Had the enslaved people gone to Alexandria, Virginia, and sold their teeth to a dentist there, they would’ve gotten double,” Smith says.

Smith also notes that while tooth selling was common for free and enslaved people, the process was excruciating—and the agency that enslaved people had to deny slavers like Washington’s “request” for a tooth sale is negligible.

“I think a lot about the individuals, free and enslaved, Black and white, who sold their teeth or had them taken. They were permanently left with those gaps. They can never move on to that elite level through their bodily performance,” Smith says.

Considering the emotionality of her work, Smith acknowledges her anger at our history and how the normalization of dental perfection continues to impart harm today, especially on low-income people and people with marginalized racial identities.

“I had the opportunity to hold Washtington’s original dentures, and when I picked them up, I started to cry,” Smith says.

“This is an object that is connected to the entire Atlantic world in terms of its actual tangible materials—and also in terms of its intellectual, political, economic, and medical histories. The connotations that we developed during Washington’s era have real health risks and real economic risks for us today.”

How Rackham Helps

Lucy Smith has participated in the Rackham Doctoral Intern Fellowship Program and is a recipient of the Earl Lewis Fund for Outstanding Graduate Students, which allowed her to examine key archives at places like the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia, the New York Historical Society, and the New York Academy of Medicine.

“It was at the New York Historical Society where I discovered the actual receipts and extensive correspondence confirming a standardized transatlantic trade in human teeth,” she says.