In the United States, approximately 10 to 20 percent of breast cancers are classified as Triple Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC), an aggressive subtype of cancers that can spread rapidly in the body and have a higher rate of recurrence.

Rackham and University of Michigan Medical School Ph.D. candidate Kassidy Jungles is working to improve treatment outcomes for people living with a TNBC diagnosis through the combination of radiotherapy and immunotherapies, drugs designed to activate immune response.

“There’s a lot of promise as we understand how immunotherapies work,” Jungles says. “I’m interested in efficacy and in reducing off-target effects. A lot of people get really sick when they’re on immunotherapies. As a pharmacologist, trying to make those symptoms less severe is something that’s really important as we try to improve patient outcomes.”

Understanding TNBC

While other types of breast cancers have estrogen or progesterone receptors—meaning the cancer cells need hormones to grow and spread and can be slowed or stopped through anti-estrogen therapies—TNBCs are subtypes of cancer that do not feed on hormones. Additionally, other types of breast cancers produce a protein called HER2 that can be targeted with drugs to slow cancer growth. TNBC subtypes grow on their own, without hormones or HER2 telling them to do so, resulting in rapid spread and growth.

Additionally, while many breast cancers impact older, menopausal, and postmenopausal individuals, TNBC is more common in people under 40 years old. Recent research indicates that young, Black individuals assigned female at birth had a nearly three-fold increased risk of triple-negative breast cancers. The risk is also high for individuals who have an easy-to-test-for inherited genetic mutation known as BRCA1, impacting individuals across all ethnicities.

While every individual diagnosed with TNBC will work with their doctor to create a treatment plan built for their specific needs, TNBC is typically treated with a combination of therapies such as surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Unfortunately, cancer returning to the body after a period of remission is common with TNBC.

According to Jungles, one reason for this could be the fact that TNBC is an umbrella term used to describe many different cancer subtypes—the only thing that really brings all TNBC subtypes together is their lack of hormone and HER2 receptors—but current treatments are not built for complexity.

“TNBC treatments are currently kind of ‘one-size-fits-all,’” Jungles says. “But not all patients respond to therapy in the same ways. There’s a lot of work that needs to be done to really understand more about breast cancer as a whole and different subtypes.”

Currently, Jungles is researching the use of radiotherapy on TNBC used in tandem with a small molecule that targets a key cellular checkpoint responsible for cancer growth and spread.

“If we can cut off this checkpoint that is acting as a regulator of cancer cell division, we can essentially kill the cancer cells. This approach also allows us to have more specificity towards the cancer cells than the healthy cells in the body, which could reduce treatment symptoms,” Jungles says.

Shifting Perceptions

At a recent American Association for Cancer Research annual meeting, Jungles met a young, Black patient advocate who was working to increase the inclusion and representation of patients with TNBC. The advocate had been diagnosed with TNBC while in her mid-twenties.

“Her oncologist gave her a packet with an older white woman on the cover, and she just kind of felt like she wasn’t seen—that’s not who she was,” Jungles says.

This lack of representation has far-reaching consequences, impacting everything from resonant communication about regular breast exams to the outcomes of clinical trials.

“TNBC impacts young women of color predominantly, but with our clinical trials, a lot of the patients that enroll are older white women,” Jungles says.

She adds that there’s currently a lot of work underway to increase the diversity of patients in clinical trials to better understand the disparities and outcomes of breast cancer patients.

“It’s really important to realize that cancer can happen at any age and certain subtypes like TNBC are more common in younger women and Black women,” Jungles says.

“It’s definitely an important dialogue to keep bringing forward—I’m grateful to the patient advocates who are working to bring about this change in the field, increasing representation and helping people connect to the care that they need.”

How Rackham Helps

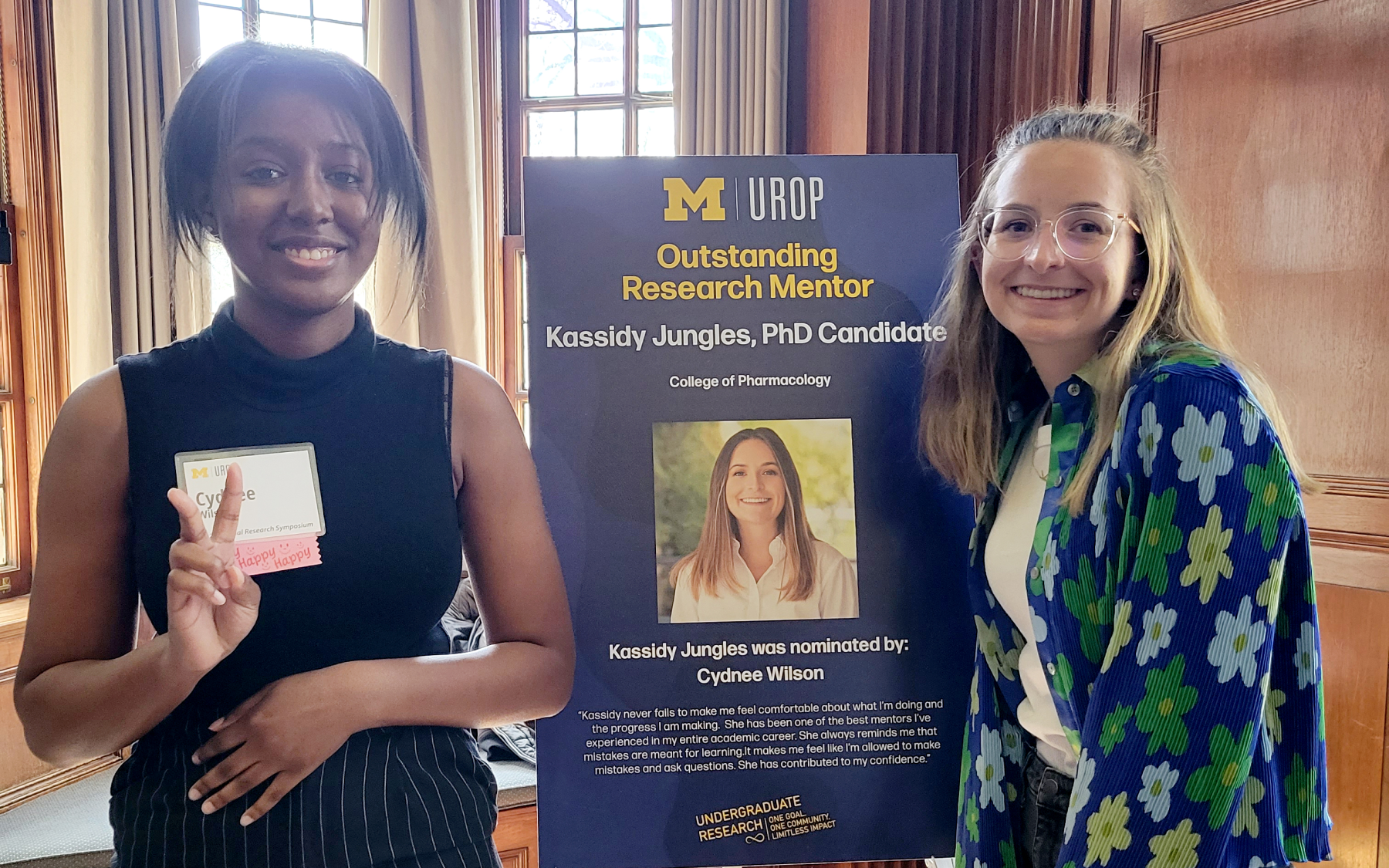

Kassidy Jungles is a Rackham Merit Fellow, a Rackham Graduate Student Research Grant recipient, a 2024 Rackham Predoctoral Fellow, and a 2024 inductee to the Bouchet Honor Society. She is also an alum of Rackham’s Summer Research Opportunity Program (SROP), a program she credits with helping her chart her course to graduate school as a researcher.

“I loved SROP. Honestly, I think it was one of the best things that happened to me during my undergraduate years, especially as I’m the first person in my family to attend college,” she says.

Now in a position to pay it forward from her vantage point as a Ph.D. candidate, Jungles works to create in-roads for women and first-generation students like herself through the pharmacology department’s summer STEM program for local students, Wolverine Pathways, and by mentoring undergraduate students in the lab.

“It’s really important for me to do what I can to increase the inclusion of underserved groups in STEM,” she says. “Without diverse viewpoints, we really wouldn’t be where we are in science today—and we need to have even more diverse viewpoints to bring about change.”