“I couldn’t have written the script for the path I travelled.” For Rackham alum George Hoey, grad school wasn’t in the original plan. Then again, neither was playing in the NFL. If you ask him, he’ll tell you the plan didn’t really exist.

Hoey was born in a small town in South Carolina, where he lived until his family moved to Flint when he was 13 years old. Having lived in an area that was still racially segregated, moving to Flint was something to get used to. “I had to deal with the integration/desegregation part of going to a new school and making those adaptations and adjustments, thinking to myself, ‘OK, you haven’t gone to school with anybody who’s white before in your life. You’ve got a homeroom teacher, and she’s a white lady. All of your homeroom teachers before have been African American. Getting support from family and friends through all that helped me to be able to function within that context, to begin to think somewhat differently.”

A self-proclaimed “scrawny little high schooler,” Hoey played football and ran track at Flint Central High School. His coach, Bob Leach, and his brother Dick were both U-M grads, and they encouraged Hoey to consider the idea of playing on the Michigan football team. He was a solid B student, and education had always been talked about as a top priority in his family, but he says, “There was really no map for me to go and get a college degree.” When it came to athletics, he recalls, “I played because I loved it. Of course, I talked about what it would be like to play for the Redskins up the coast, but that wasn’t a driving factor.” His mother always told him, “You’re going to be the best student you can be, and you’re going to be the best person you can possibly be,” so when it came to sports, Hoey wasn’t going to let them define him.

Hoey encourages graduate students to remember that their program of study does not define them. “Whether it’s taking additional courses within your discipline or outside of your discipline, just be that interdisciplinary person and take that approach if the program isn’t designed that way by choice. Venture out. Be exploratory. Be your true self. Shape and define that degree in the way you want.”

Though recruiters were coming to visit him left and right, Hoey says the offers just didn’t feel right. That is, until his conversation in the Michigan Union with then football coach Bump Elliott. Hoey says Elliott was honest with him about the little playing time he could promise, since he was being recruited as a running back and they had two sophomores currently playing that position. “But one thing I can tell you,” Elliott said, “is that you’ll have the opportunity to get a great education from the University of Michigan.” It was that moment that Hoey decided he was going to Michigan. He became the first African-American student from the city of Flint to receive a U-M athletic scholarship.

From Ann Arbor to the NFL

He moved to Ann Arbor in the fall of 1965, and during his time as an undergraduate student, Hoey studied physical education and planned to go back to Flint to teach and coach, “who knows for how long.” Two years after graduating, Hoey was drafted by the Detroit Lions, and so began his career in the NFL. In the offseason, Hoey continued teaching at a middle school in Detroit. “It was right in the middle of the ‘combat zone’ where the riots took place in the ’60s. I had done my student teaching in Ann Arbor, and it was so different, but it was a good experience.” Hoey still wasn’t sure teaching was his calling, but he enjoyed it until he received a phone call from Bob Hollway, the head coach of the St. Louis Cardinals (now of Arizona) who was once Hoey’s defensive line coach at Michigan, and Bob Leech, the defensive line coach for the Cardinals who was Hoey’s coach during his time at Flint Central. They told him, “George, we know you can play, so we want you to come to St. Louis.”

Hoey’s professional playing career lasted six years and took him from St. Louis to New England, San Diego, Denver, and New York. It was during a camp scrimmage at this last stop that he had a revelation. “Gordon Bell, who played at Michigan, too, was the running back for the Giants, and he was coming my way. I thought I was going to knock him dead, but he put a move on me and I thought, ‘Whoa! What just happened? I didn’t even touch him. Maybe that means you’re losin’ it, old man.’” He alerted head coach Lou Holtz of his retirement shortly afterward.

His Return to Ann Arbor

After Hoey hung up his jersey for good, he returned to Michigan. After a couple weeks of decompressing and a nudge from his then wife, he began the job hunt and landed a position with U-M’s undergraduate admissions office. He served as a type of liaison to athletics, and in that role, he got to interact with students who were being recruited and thinking about coming to Michigan—the same position he once found himself in. He recalled how different the previous six years in the NFL had been compared to his time on the Michigan football team, and he thought, “If I could work with college [athletes] who were aspiring to be in the pros, I would love to do that.”

In 1974, then head coach Bo Schembechler hired former football player Jim Betts to run an academic support program for the football and basketball teams. Hoey expressed his desire to work with that population of students, and after a meeting with Schembechler and then athletic director Donald Canham, who had also coached Hoey in track at Michigan, he began his role in the academic support program for athletes. He stayed in the role for 15 years and “loved every minute of it.” He travelled with Schembechler and represented the academic side of their operation as they teamed up to recruit potential Michigan athletes on the weekends.

During that time, his commitment to education was not only at play during his working hours. Professor Percy Bates, the faculty athletics representative from the School of Education asked Hoey the question that led him to his time as a Rackham student: “When are you going to get your master’s?”

Hoey had been regularly working 15-hour days and hadn’t really pictured graduate school in the cards, but Bates pushed him and told him about a scholarship program and the possibility of taking only a couple classes at a time to get started. After a bit more hesitation, Hoey took a chance and signed up for two classes during the following spring semester. In 1986, he completed a master’s degree in guidance and counseling. “I didn’t see it at the time, but it made so much sense. I was really running more a life skills program than purely academic support.”

His Commitment to Diversity and Inclusion

Percy tried to convince him to start taking steps toward his Ph.D., but in 1993 Hoey moved to Boulder to work in athletics administration for the University of Colorado. There, he ran a life skills program for student athletes for six years before moving into student affairs. He spent the 18 years that followed working in the school’s career center.

“The counseling program [at Michigan] afforded me the luxury of being able to transfer some of those skills into the career arena.” Hoey strived to help students understand how important it was to plan for themselves and truly define who they were before letting a professional sports league do it for them. “I just wanted to assure them that, ‘Hey, you’re a person, you can function and you need to learn as much as you can whether you’re going to the NFL or not.’ That was my approach. Sometimes I felt as if I was working on an island, but still I pushed it.”

Hoey also says he had the opportunity to work closely with diversity and inclusivity issues on campus and in the community, working with both undergraduate and graduate students. “I just loved all the work that I was able to do, and I appreciated being able to function within that context.”

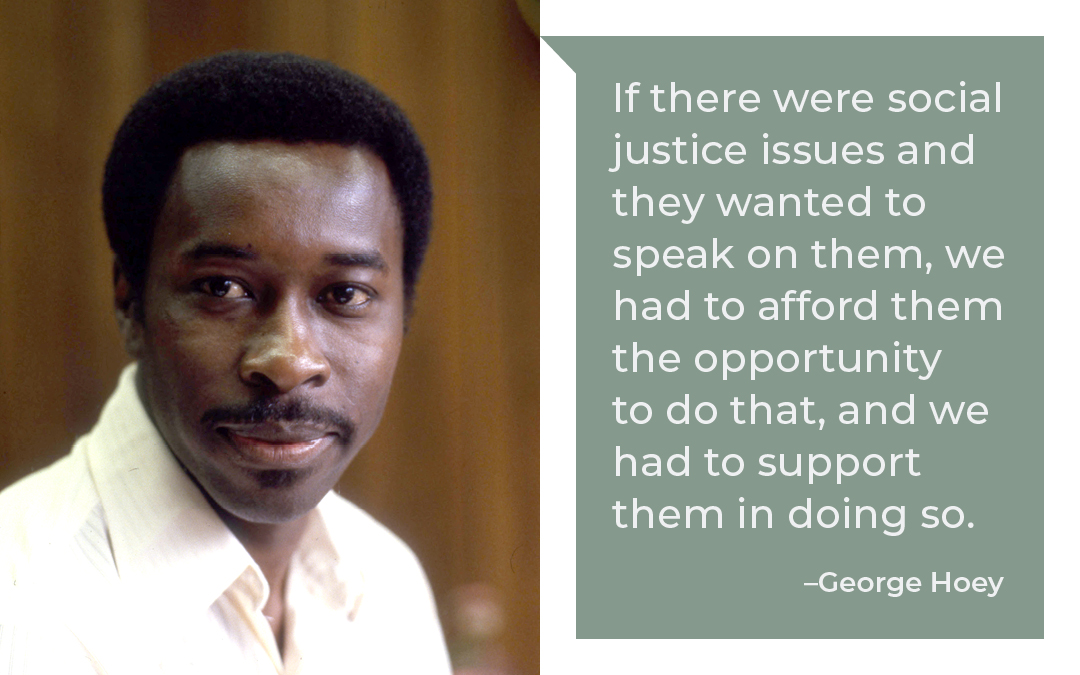

Hoey recalls his time sitting on the planning committee for one of the diversity summits at the University of Colorado at Boulder, one of which revolved around the events in Ferguson, Missouri following the death of Michael Brown. “There were some really gifted and talented graduate students there, but it took 20 minutes into a 75-minute program before those students were really able to have their voices heard.”

He began working with other faculty mentors who could directly address the students’ concerns and provide support outside of the classroom, allowing opportunities for students to weigh in. If there were social justice issues and they wanted to speak on them, we had to afford them the opportunity to do that, and we had to support them in doing so.”

After a total of 42 years working in higher education, Hoey is retired and enjoying time with the love of his life, Erin, whom he married in 2001, and their two sons, William and Sean. He was inducted into the Greater Flint Afro-American Hall of Fame in 2001 and the Greater Flint Area Sports Hall of Fame in 2003.

Acknowledging the impact that others had in his life, Hoey offers this suggestion for his fellow alumni: “I hope others will treat the word ‘alum’ as a verb rather than a noun. Be active, support and engage with students. Wherever you are, you can make a contribution, whether it’s monetary or it’s sitting on boards, submitting research articles, or sharing your skills. Just treat it as a verb.”