Colin Quinn’s anthropology research has taken him far from campus to the gorgeous landscapes of the Romanian countryside where he’s uncovered the artifacts he’s sought – and some unexpected treasure as well.

Ph.D. research can be a laborious endeavor, and the rewards are often more than a well-crafted dissertation. In Colin’s case, he unearthed a profound experience that connects his research to building a local community’s self-identity.

Colin’s dissertation seeks to understand the organization and political economy of metal and its changing role in the development of social complexity throughout the Bronze Age. His is a unique combination of anthropology and archaeology, two approaches that can provide insight into the human past and present. A groundbreaking study, his research is the first systematic archaeological survey related to an anthropologically-oriented study of communities in metal procurement zones in the central region of Romania (better known as Transylvania). He laughs and explains, “This region is like a Bronze Age Costco – a resource-rich environment ‘all under one roof’.”

There are interesting parallels between the Bronze Age and today in terms of the issues of social justice, exploited workers and control by the elite ruling class. By assessing the distribution of metals and artifacts from the Bronze Age, Colin hopes to draw conclusions related to the development of institutions of inequality. The role archaeology plays in policy development helps test what strategies work(ed) and didn’t work throughout the ages. This is the utility of archaeology in anthropology: the influence on how the collective human past can inform decisions we make today.

While spending time in a small Romanian community, Colin became closely tied not only to researching its history, but found himself captivated by the people and the current threats they face. The surrounding region is the proposed site for a controversial open-pit gold mining project that would effectively raze four mountains and create a toxic lake from the 40 tons of cyanide used per day for the project. This region is home to ancient Roman mines of such historical significance that they are being considered for protection as a Unesco world heritage site. The open-pit mine would mean the end of many aspects of this community, including ties to the ancient mining history of the region.

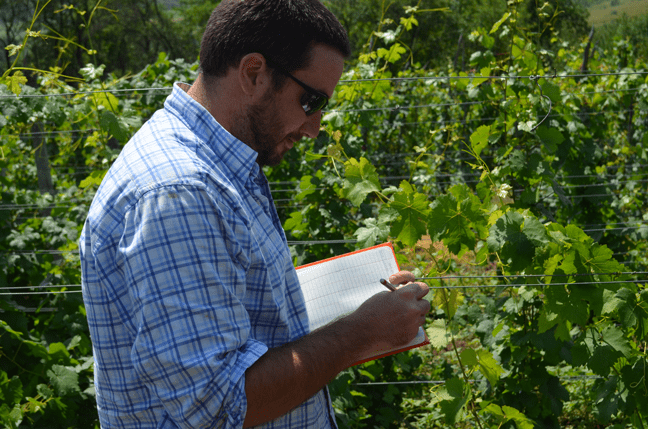

Outside the scope of his research, Colin got involved in a heritage revitalization project in the local village of Bucium to help the community identify with its mining history before its potential loss. Rackham provided the funds for this project through the Arts of Citizenship program, which allows graduate students to develop collaborative projects with community partners that address real-world challenges and enhance students’ professional development and strengthen and expand their public scholarship.

For the Bucium project, with the help of his community partners Dr. Horia Ciugudean and Viorel David, Colin met Simion Narita, an 83 year-old miner, and asked him to demonstrate traditional mining techniques—in effect sharing a lost art with the threatened community. The project was about the cultural revitalization and ownership of the past, in a community trying to re-claim their history and find new ways of integrating it into their current identity. The result was beyond what Colin had ever expected.

“I wanted to get great photos of the mining tools in action, but as the miner sat down and started to pan, everyone rushed over and created this wall of humanity, swamping me out on the sidelines. I was frustrated at the loss of photo-op at first, but realized that the excitement for traditional practices and interest in their own past that I was trying to create had really happened.”

The proposed gold mining in the region has led to the largest uprising of protesters in Romania since the overthrow of communism in 1989. The proposal has since been rejected by the Romanian government, but the issue is likely not over.

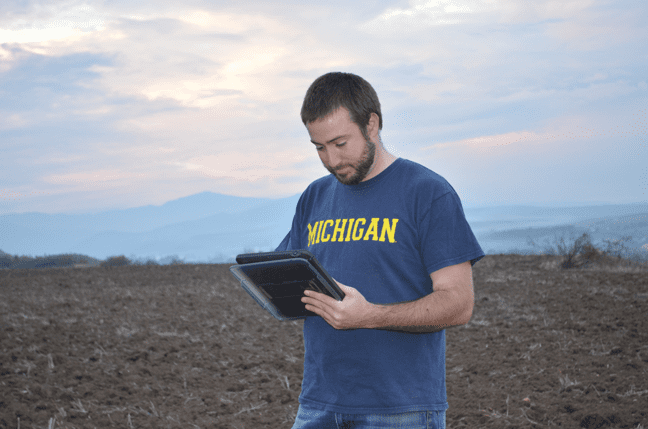

While the future of the region is unsettled, Colin plans to return to Romania in the spring for a few more months of 11-hour field days. One of his favorite aspects of fieldwork is that this takes the museum directly to people, where he spends a surprising amount of time answering questions from passersby, both from around the corner and around the globe: “People can see how research is conducted and the fact that there is a lot of work collecting the 0.1% of artifacts that actually are displayed in a museum. I can show how we learn from and analyze items, a hidden part of a museum. It gives narrative to the work.”

Indeed, the narrative of Colin’s time in Romania reflects not only new research on historical mining implications for social inequities but also a passionate interest in helping modern communities raise awareness of their cultural heritage. “Michigan – Rackham – makes this possible. Students and faculty here do innovative and cutting edge research and the students move on and apply it globally, expanding Michigan’s reputation and influence around the world. The uniqueness of the program that makes Michigan ‘Michigan’ wouldn’t exist without Rackham.”