When I came to graduate school to study chemistry, I suspected that I would have to expand my skill set to succeed. Experimental design has a tendency to draw from many different areas of expertise. It’s not enough to be a good chemist; you have to be a good chemist who is part electrician, part engineer, part computer programmer. But, now in my fifth year, I figured those days were behind me and I’d finally gotten a handle on the whole thing.

Nope.

In my research, I search for new ways to make metal oxynitrides – solid crystalline powders composed of one or more metals, oxygen, and nitrogen. To do that in a controlled way, I need to exclude oxygen from my reactions, which take place at a balmy 750 ºC (~1400 ºF). That’s easier said than done, considering you’re bathing in 20% oxygen right now.

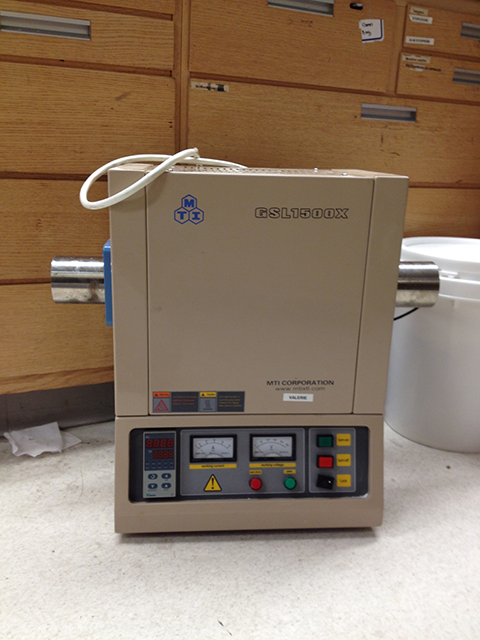

To get high temperatures and artificial atmospheres at the same time, I use a specially-shaped oven called a tube furnace. Every single reaction I do gets processed in the tube furnace. If it breaks, I’m dead in the water.

This is a tube furnace.

So, of course, right before the winter break this past year, it broke.

The first round of replacement parts didn’t fix the problem. The company was really great about working with me over email to do some troubleshooting, but nothing we did got the furnace up and running. The company replied with an email asking me to send the furnace to California “in a wooden crate.”

I did a double take. Really? Should I request to have it shipped on a wooden frigate as well? Request that it takes the long way around Tierra del Fuego for old time’s sake? Where was I going to find a wooden crate?

Fortunately, another lab had just had an instrument shipped to them in a wooden crate. They told me I could use it if I wanted, but it was about four times bigger than what I needed. Buying a new crate of a more reasonable volume was going to cost $150 plus the time it would take to get there, and at the time I had already lost over a month’s worth of work.

I went back to my lab to complain about my woes. My labmates Charles and Adam didn’t really see the problem, though. “If there’s all that wood there,” they said, “why don’t we just hack it up and build a smaller crate?”

I don’t know how to build a crate, I thought. Where would we get the tools? Where would we do it? Is that even safe for the furnace?

Obviously, Charles went to get the SKIL saw that he just happened to have at his apartment because this was going down right then in the hallway outside of the lab. Building a crate is easy, and as far as the furnace goes… the company wants you to insure the package anyway, right? My labmates dropped everything they were doing that day to help. I insisted that they were doing me a huge favor and that they didn’t need to help me with my problem, but their response was basically, “Are you kidding? I get to use a saw for science!”

The building of the crate begins.

So we took three hours and rebuilt that crate right in the hallway. The other chemists walking through the department either gave confused looks as they walked by or stopped to check the project out. Most chemistry labs in our department are not solid-state labs, so the idea of needing a specialized furnace seemed to fascinate the people who stopped to talk. It seems silly, but carrying on with my friends, working on a simple-but-not-so-simple project together, and chatting with other department members outside the workaday lab space (even if it was only twenty feet away) is going to go down as one of the most fun work days of my life.

Experiencing the crate from the inside.

Finished!

The final product, with the furnace tucked securely inside, weighed 140 pounds and cost about $300 to ship to California. By building our own crate we saved at least $150 and a week’s worth of research time. My buddies got to get their power tools out and have a good time in the name of science, and I guess I can add amateur carpentry to my resume because the crate made it to the company in one piece. Now I just have to wait for it to come back… someday…