On New Year’s Eve, 2019, health authorities in the Chinese city of Wuhan reported a cluster of viral pneumonia cases of unknown cause or origin. While they didn’t know it at the time, these were among the first cases of a new disease, now known around the world as COVID-19, that would spark a global pandemic and upend virtually everything about the way we live our lives.

The virus quickly spread around the world, with governments and public health officials scrambling to keep up with it. As infection rates and death tolls climbed in countries like China, Italy, and the United States, Rackham biostatistics Ph.D. student Rupam Bhattacharyya and his colleagues at the U-M School of Public Health and other institutions realized that India’s COVID-19 cases were lagging about two to three weeks behind its counterparts in Europe and North America.

“When we looked at the curves—the number of cases and number of deaths in different countries—we saw that India was farther behind in the COVID-19 timeline than other places,” Bhattacharyya says. “That meant there was still time to look at different factors and make some recommendations before the virus firmly established itself.”

With over 1.3 billion people and a population density of approximately 1,200 people per square mile, the high infection rate of COVID-19 would prove devastating if left unchecked, Bhattacharyya says. In order to help policymakers make the most informed decision possible, he and his colleagues from U-M, Johns Hopkins University, the University of Connecticut, and the Delhi School of Economics formed COV-IND-19, a research group aimed at modeling the impact of different nonmedical interventions on the pandemic in India, as well on the Indian economy. These include national lockdowns of varying intensities, as well as different levels of public cooperation with lockdown orders.

To achieve this, the team took a model previously used by a different research group to successfully model the pandemic in China and adjusted its parameters and assumptions to reflect the unique conditions in India. This is where Bhattacharyya’s expertise in computational medicine, normally applied to modeling the effect of different treatment regimens on cancer patients, proved invaluable.

“That was my role, modifying the model to work in the context of India,” Bhattacharyya says. “We wanted to gauge the entirety of what was happening and what could be done, including using data from how other diseases have spread in India in the past.”

As expected, the model predicted the scenario in which India did little to constrain COVID-19 showed an exponential rise in infection rates as it cut through the country’s densely populated urban centers. Further scenarios that incorporated measures like travel bans slowed the disease, but not enough to avoid stressing India’s healthcare system to its limits. The model did, however, show that measures like lockdowns, when coupled with quarantines and other tactics, were effective at flattening the infection rate to a manageable level.

“We’re still refining the numbers, but the pattern is clear,” Bhattacharyya says. “It’s prudent at this point to say that the best way to flatten the curve is with a lockdown that has high compliance from the public.”

Spread Data, not Viruses

With their model working, the COV-IND-19 team set out to get it in the hands of people who could use it. They built an online dashboard showing their projections, which is updated routinely with the latest data, and published several articles for both academic and general public audiences. They were also contacted by public health officials connected with the Indian government’s COVID-19 response team.

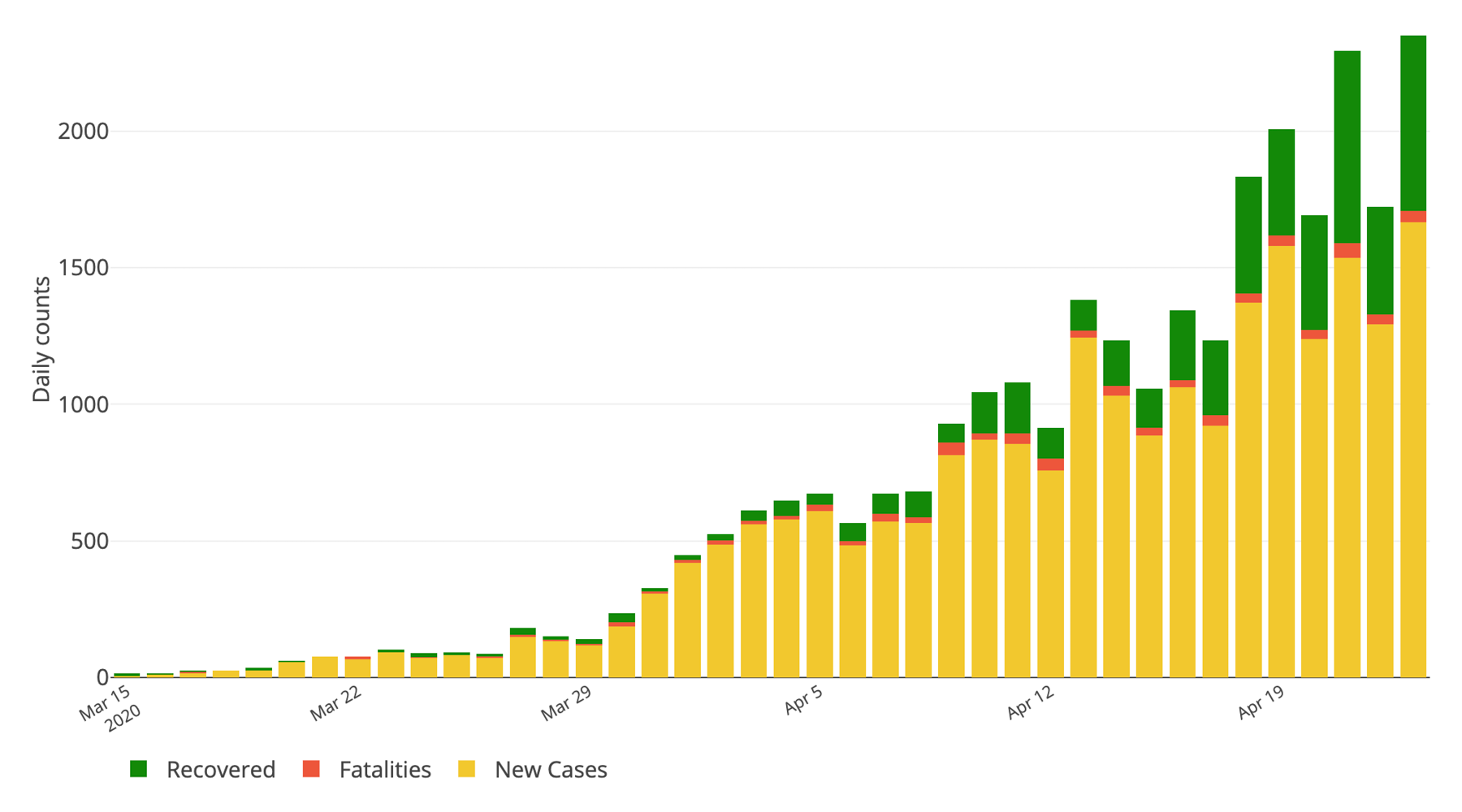

This screen capture from the COV-IND-19 team’s web dashboard shows the rising number of COVID-19 cases in India.

“Our primary target with this data was public health officials in India, and I’m very pleased we were able to reach them,” Bhattacharyya says. “But we also wanted people of all backgrounds, all levels of scientific understanding, to have access to this. When you’re trying to tackle a pandemic, the solution doesn’t come from just the government or just the people, but from both of them working together.”

See the COV-IND-19 dashboard at U-M Biostatistics.

Rackham Students: Are you working on COVID-19 issues? Finding new ways to move your scholarship forward at this time? Discovering effective practices for remote teaching? We’d love to highlight your story. Just email us at Rackham Communications.

Interested in supporting Rackham students? Make a gift to the Rackham Graduate Student Emergency Fund.