The impostor phenomenon (IP)—when people experience feelings of self-doubt about their accomplishments and abilities along with a fear of being exposed as a fraud—has been shown to be common in academia among students from all different backgrounds, disciplines, and levels of study. Danielle Rosenscruggs is a Ph.D. candidate in developmental psychology whose research looks specifically at the roles social identity and context play in impostor experiences within doctoral education and how to mitigate those experiences.

She recently co-authored a chapter with Rackham Senior Academic Director Laura Schram on research-based strategies for combating the impostor phenomenon in higher education. The chapter was published last spring in a book edited by University Diversity and Social Transformation Professor of Psychology Kevin Cokley titled The Impostor Phenomenon: Psychological Research, Theory, and Interventions.

In this Q&A, Rosenscruggs discusses impostor cycles, strategies for overcoming them, and the paramount importance of institutional change in promoting inclusive, welcoming, and equitable academic environments.

I had always heard of this referred to as “imposter syndrome,” and I thought an interesting place to start might be by hearing you discuss the shift to “impostor phenomenon” and what that means.

Danielle Rosenscruggs: It’s interesting that most people understand it as having started as “imposter syndrome” and now shifting towards “impostor phenomenon.” However, when doctors Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes first labeled these experiences in the 1970s, they used the term “impostor phenomenon.” I don’t know when the change occurred, but my understanding is that the popular press played a role in the terminology shift. But in their original scholarship, Clance and Imes never presented it as a clinical diagnosis or pathology, and even today, Clance speaks out against the “syndrome” label.

I try to be very intentional with the language I use in my scholarship and workshops because words are powerful. In psychology, a syndrome refers to a specific set of symptoms characterizing a mental disorder, while a phenomenon describes a general observable experience or behavior that may not imply pathology. So, labeling it “impostor syndrome” pathologizes it and creates an implicit narrative that impostor feelings are a disorder needing to be fixed, suggesting there’s something wrong with the individual. On the other hand, referring to it as a “phenomenon” acknowledges its commonality, highlighting that many people experience it to varying degrees and that it’s not a disorder to be cured.

Could you describe what you mean when you talk about “imposter cycles”?

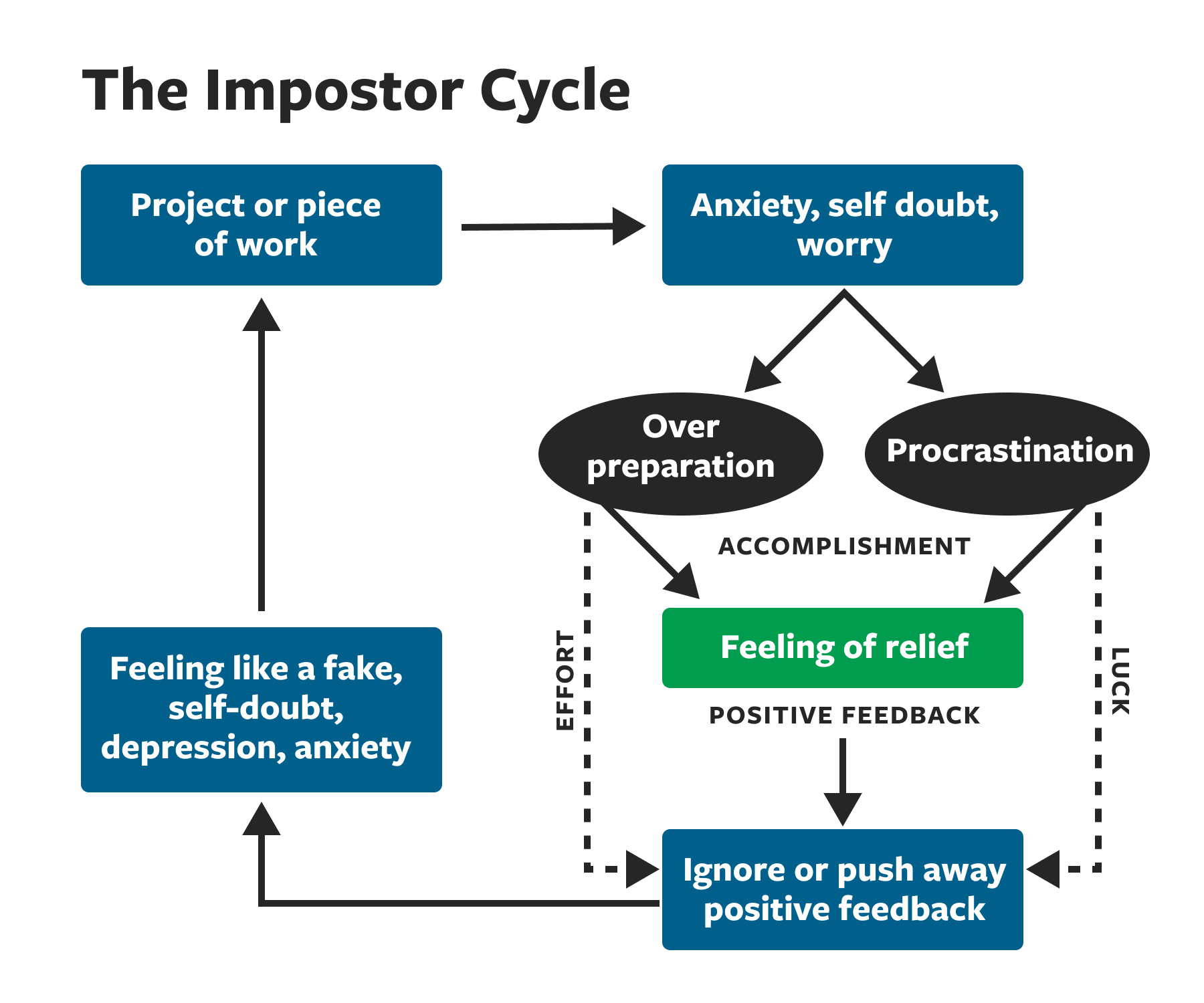

DR: Sure! Typically, there are two paths that people take in their imposter cycles—and when I say “paths,” I mean how impostor feelings, like feeling like a fraud or fearing like they don’t belong, get navigated and addressed once triggered. Those two commonly discussed paths are the perfectionist path and the procrastinator path.

With the perfectionist path, people deal with their fears of being exposed as frauds by working excessively. They become convinced that if they just put in “enough” work, waiting until the paper, project, etc. is just right (or perfect) before considering it finished, they’ll be able to continue fooling everyone. However, when they get positive feedback, they tend to think, “Oh, it’s just because I did all this work. I’ve succeeded in tricking them, so now I have to continue putting in this amount of work.” And the cycle continues.

On the procrastinator path, people’s fears of being found out prevent them from starting their projects or tasks. They put off assignments and projects until the last minute and then work frantically to get the work done—for example, by pulling all-nighters or neglecting other responsibilities. Then, the negative feedback loop starts when they receive positive reinforcement: “Oh no, now people will have high expectations, and I’m not going to be able to maintain this.” That causes them to procrastinate again.

People don’t necessarily follow only one path—sometimes, it’s a combination of the two. You might have someone who procrastinates but then holds themselves to unrealistic standards once they start working. Really, it’s like any other kind of cognitive-behavioral loop or thought pattern. You do things to ensure you’re not found out, and when you get great feedback, you become convinced it was only because you put in all of the effort or got lucky—not because of your talent, intelligence, or skills.

The Imposter Phenomenon cycle (Clance et al., 1995).

Are there differences in reported feelings of imposter phenomenon along racial and gender lines?

DR: This is actually very complex and nuanced. The research is a bit murky when it comes to gender or race/ethnicity-based differences in IP, so I try to avoid speaking definitively about this topic. Although some studies have found apparent gender-based differences, typically with women experiencing higher IP levels compared to men, others have not. And when it comes to race/ethnicity-based differences, little work has been done directly comparing experiences across groups. So, any claims of group-based differences in that regard would be a bit premature, especially since few studies explore the potential impacts of other factors like socioeconomic status, first-generation status, and nationality.

Social context, positionality, and power systems appear to play a role in developing and perpetuating IP experiences. Unfortunately, these factors have only recently begun to be considered, at least in quantitative IP research. So, it’s possible that previously observed gender or race/ethnicity-based differences are driven by larger social forces and complex identity experiences. More research is definitely needed in this area to ensure we are not miscategorizing reasonable reactions to oppressive environments as innate differences.

That ties in with a line that stuck out to me from your chapter: “Institutions generally committed to supporting the well-being of their students must stop placing the entire burden on the individual and work toward high-level structural change.” What does that change look like to you in terms of addressing IP?

DR: I love that that line jumped out to you because it’s something that I feel very passionately about! A lot of my work focuses on individual-level strategies because that’s where the research currently exists. But my take—not from my research but from what I read and my opinion and perspective—is that higher-ed institutions put a lot of focus into making admissions more accessible. However, once folks arrive on campus, institutions don’t always think about how the systems in place were built for certain types of students… upper-middle-class white men. So when you start expanding access—which is amazing—before changing the culture and systems, you set students up to feel like they are frauds who don’t belong.

So, how do we create more inclusive environments? How do we provide structured mentoring programs? How can we better expose hidden curriculum through formal training? Because, at least at the graduate level, we’re not teaching essential skills that are crucial to student success, like time management, finding and working with mentors, or reading scientific papers. Many of those skills are only discussed in extracurricular workshops and programs, sending a clear message from the university and departments that they are not considered core parts of academic training.

I think as long as we keep these essential skills trainings on the periphery, we keep the people they are meant to help on the periphery. Integrating these skills into the core curriculum could significantly minimize feelings of fraudulence and not belonging. It would send the message that these are essential skills everyone needs to know, and therefore, they will be taught to everyone rather than assuming students will figure them out on their own.

Looking at it from the other way, what are some helpful strategies for individuals to keep in mind as they’re trying to address their own negative thoughts?

DR: Although research in this area is still pretty limited, there is strong evidence supporting two approaches that are effective in minimizing IP. The first involves cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques, focusing on cognitive reframing and retraining. This approach involves recognizing negative self-talk, acknowledging it as a rehearsed pattern of self-criticism, and then actively reframing it towards possibility, curiosity, and understanding. In our workshops, we include exercises that highlight the contrast between fixed and growth mindsets. Someone with a growth mindset views intelligence as expandable through effort and learning new skills, whereas, someone with a fixed mindset believes intelligence is innate and unchangeable. Fixed mindsets have been associated with higher levels of IP. Folks with this type of mindset can get trapped thinking, “I’m succeeding because I’m tricking people.” However, with a growth mindset, they might think, “I’m succeeding because I learned something. I went out and got this new skill. I’m contributing.” Research has shown that mindsets can be shifted with time, coaching, and effort, so it’s a great place to start.

Another effective approach is mindfulness and self-compassion training, which aligns closely with my focus. Mindfulness emphasizes de-identification from one’s thoughts—recognizing that thoughts are not defining of oneself—and the practice of self-compassion. This involves understanding personal challenges as part of a shared human experience rather than as personal failings. These practices help counteract the inner critic that often drives impostor feelings, replacing self-criticism with self-compassion and a broader perspective. So, thoughts like, “I’m a fraud and I don’t deserve to be here,” are replaced with, “Grad school is really hard and that’s why I’m struggling.” However, these shifts take time and require dedicated mindfulness or self-compassion practices.

In your work on this topic, has anything stood out that was particularly surprising or unexpected?

DR: One thing that fascinates me is how eagerly most people want to claim impostor status. If I were to tell people I studied depression, I wouldn’t expect those who have struggled or are currently struggling with depressive thoughts to excitedly proclaim their experiences. Yet, whenever I mention that I study IP, everyone is eager to self-label as feeling like a fraud (or being a fraud). This eagerness seems counterintuitive to me since I would assume folks who fear being exposed as a fraud would avoid the label. I suspect that in many cases, people are confusing normative feelings of inexperience, self-doubt, or insecurity with IP, but it’s hard to be sure. It’s definitely something I would like to explore in future research!

Whatever the case, I still believe it’s important that people have access to those individual strategies I mentioned. There are enough people who feel like they are drowning and need “life vests,” and so I think programs like ours are really vital. However, we can’t solely rely on individual solutions. While they can be helpful, systematic change is essential. We need to shift the burden away from students suffering under systemic weight. It’s not their responsibility to bear this alone, and we should equip them with tools to navigate inequitable systems while we work toward larger change.

Read more in “Research-Based Strategies for Combating the Impostor Phenomenon in Higher Education” by Danielle Rosenscruggs and Laura Schram