Kimberly Ransom did not come to graduate school to study history, much less her own.

Apart from stories of her grandparents coming north from Pickens County, Alabama, in 1959, Ransom learned little about her family history while growing up on Chicago’s south side. During her graduate studies at the U-M School of Education, however, she ran across something familiar—the Rosenwald school program.

A collaboration between Tuskegee Institute president Booker T. Washington, Sears and Roebuck president and Jewish American immigrant Julius Rosenwald, and rural African American communities, the Rosenwald program built over 5,000 schools throughout the American South, providing state-of-the-art educational alternatives for Black children otherwise forced to attend critically underfunded public schools.

Most Rosenwald schools were broad wooden structures, painted white and built on short stilts. Ransom recalled her mother describing exactly that kind of building when talking about her own school, and that piqued Ransom’s curiosity.

“Knowing little about the histories of your family, particularly the childhoods of your parents and grandparents, is typical of the descendants of slavery that I know from Chicago,” Ransom, a doctoral student in the Educational Studies and Museum Studies programs, says. “If your parents migrated north, they often left those stories behind. But after reading about the Rosenwald schools in class, I wondered if there was a connection.”

Going Back to School

An internet search led Ransom to discover Pickensville School, a Rosenwald school in her mother’s hometown. Though it closed in the early 1960s, it still boasts a strong alumni association. Reaching out to the association, Ransom was put in touch with members Ora Austin and Paulette Locke-Newberns.

“Ora knew my family, my grandmother, everybody,” Ransom says. “She wrote a book about the six Rosenwald schools in Pickens County, including Mamiesville Elementary, where my mother attended and my grandmother taught. That was my portal into what became an abyss of data that began to breathe life into a topic we don’t often talk about—Black childhood.”

Ransom found that the experiences of the children themselves were often absent from the history of school segregation. She connected this with wider trends that ‘adultify’ Black children in the media, linking them with stories about police brutality, crime, the academic knowledge gap, but rarely with traditional childhood attributes. This is a narrative she believed her new connection with the Pickens County Rosenwald community could help correct.

“In America, childhood status is connected with naivety, wonderment, and innocence,” Ransom explains. “These are things we don’t foreground when discussing or depicting Black children. I’m hoping my research will provide a window into Black childhood and what childhood experiences and agency look like through their eyes.”

In 2002, the National Trust for Historic Preservation placed the Rosenwald Schools, like the Pickensville School pictured here, on its America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places list.

With help from Locke-Newberns, Austin, the Hopewell Rosenwald School Alumni Association, and others, Ransom sought to interview Pickens County Rosenwald alumni and put together an oral history of their childhoods. While her list of subjects started small, it quickly snowballed. Each subject often knew several more willing to participate, some of whom even remembered having Ransom’s grandmother as their substitute teacher. Ransom heard stories about children walking to school on dirt roads and through inclement weather, but also smelling spring flowers and stopping at people’s homes for fresh bread or to warm their hands.

“There was no doubt among the children that these were dangerous times, living in the Jim Crow South, and that they had to navigate these dangers,” Ransom reflects. “Within that world, children described other dangers from their perspectives—rattlesnakes, vultures, fear of the dark—but they still accessed childhood joys with their friends. Despite the ever-present limitations of segregation and racist social norms, they used their agency to seek fulfillment in the everydayness of their lives, studying, working, and helping their friends advance, friendships that have endured to the present.”

While Ransom scoured what few local archives she could find, the informal archives hidden in her subjects’ closets and attics proved far more valuable. Their diaries, yearbooks, old homework assignments, and other personal effects told a more detailed story about their childhoods than any official source. She found essays and poems, often humorous and filled with playful language. She also found more harrowing accounts, like that of a young girl recalling the Ku Klux Klan marching through town, and recognizing a prominent community figure among the hooded company by his shoes. Collected together, her research uncovered a fresh view on Black childhood that showed wonder, naivety, and agency even in the midst of the Jim Crow era.

“The more I looked through local archives, the more I realized this history didn’t have a place to live,” Ransom says. “The local library had no information on the Rosenwald schools or students. They have a museum dedicated to the local World War II POW camp, but no homage was being paid to Booker T. Washington, Julius Rosenwald, and the community that built and operated six schools in the county between 1916 and 1973. Pickens County needs that story, too.”

Rebuilding the Past

The more she learned, the more Ransom felt a responsibility to those who helped with her research. At the same time, she knew Locke-Newberns and her sisters were leading work to restore the Pickensville School, the last surviving Rosenwald structure in the county, for use as a community center. That struck her as the perfect opportunity.

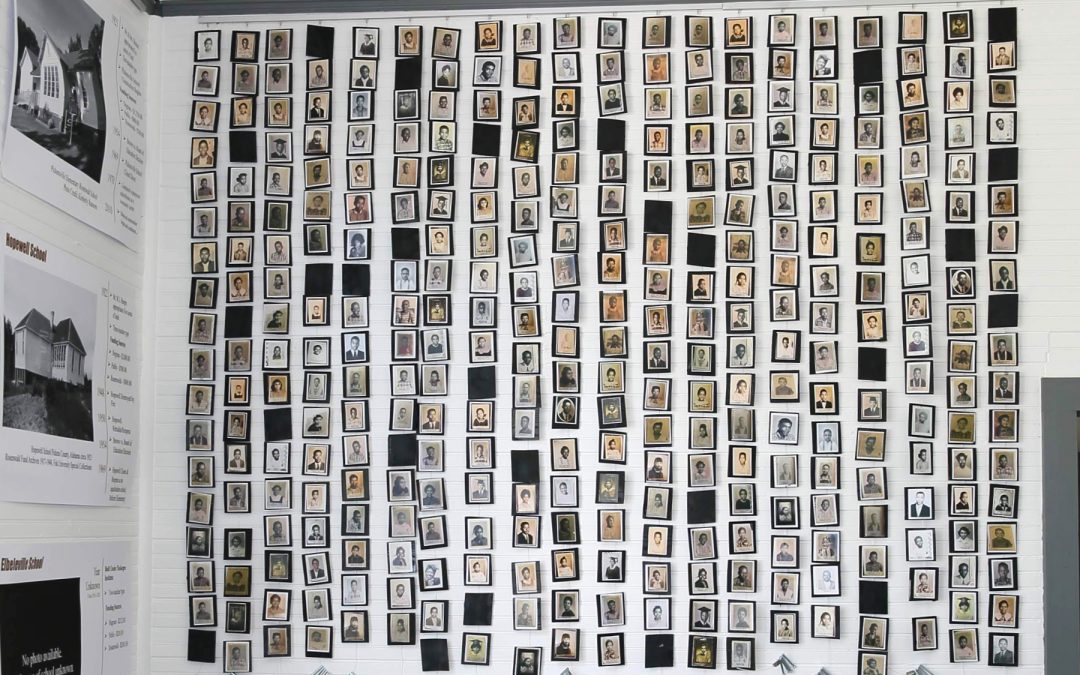

With support from the Rackham Program in Public Scholarship, the Black Belt Foundation, and the Alabama Bicentennial Commission, Ransom and Rosenwald alumni began work on a museum to be displayed at the restored school and commemorate not only the place of the Rosenwald schools in history, but the stories and voices of those who attended them.

“Finding the schools, the alumni, and their artifacts was the perfect storm to create a museum,” Ransom says. “This is public scholarship at its finest, supporting a community project, one the community itself is invested in and will keep going after the research is done.”

Left to right: Project team members Paulette Locke-Newberns, Mary Locke-Fuseyamore, Kimberly Ransom, and Caroline Locke-Wright at the Pickens County Training School All Class Reunion in Carrollton, Alabama.

By commemorating the students, Ransom hopes to add to the story of Black education in America. While past research has explored this subject, she says, it was always from the perspective of how and why Black children should be educated, without taking the children’s own perspectives into account.

“Across this history, Black children have been paper dolls on the landscape of education,” Ransom says. “We haven’t imagined them as being innocent, naïve beings with their own youthful agency who deserve the protections and support we normally associate with childhood, like education. I want to insert the perspective of Black children as children—what they were saying, thinking, and doing in and around these schools, and how they may have influenced the schools—into historical education research.”

How Rackham Helps

In addition to her Rackham Public Scholarship grant, Ransom is a Rackham Merit Fellow, which has helped her remain fully immersed in her research even as she balances it with her responsibilities as a single mother. She has attended multiple Rackham professional-development workshops on writing, which she says have not only improved her skills, but connected her with an interdisciplinary group of peers with whom she shares ideas, techniques, and support.

“I feel like Rackham does everything,” Ransom says. “Through Rackham I’ve built relationships with students across the university and beyond. Their involvement has also helped elevate the work and voices of the Rosenwald alumni in Alabama.”