While the U-M Library’s collection of ancient papyri includes pieces renowned throughout the world, Rackham Associate Dean Arthur Verhoogt finds some of the more obscure items in its catalog to be just as intriguing: A soldier’s letter home, a child’s first writing exercise, even a tax roll can provide a singular connection to people who lived thousands of years ago and a new understanding of their lives and worlds. Verhoogt was recently presented with the University of Michigan Press Book Award for Discarded, Discovered, Collected, his introduction to U-M’s papyrus collection. In our Q&A, he discusses the archive’s origins, its importance, and the thrill of opening a box that can be a window through the ages.

As a quick introduction (or a refresher), what are papyri, and where and when do they come from?

Arthur Verhoogt: Papyri are one of the writing materials that were used in the ancient Mediterranean world. Created from the papyrus sedge that grew on the banks of the river Nile in Egypt, it provided a flexible yet fairly durable writing material that could be used to write anything from works of literature to official and private letters. One would create a sheet of papyrus by pressing together two layers of papyrus strips, one horizontally, the other vertically. The result was a sheet of papyrus about the size of modern print paper. Twenty of such sheets were pasted together to create a roll. Because papyrus is an organic material, it only survives in dry and undisturbed conditions, such as the desert sand of Egypt. Most papyri were written in ancient Greek, which was the language of the elites in Egypt from Alexander the Great until the Arab conquest of Egypt, but there are also many other languages represented, such as Egyptian (in its various scripts, Hieroglyphs, Hieratic, Demotic), Arabic, Coptic, Aramaic, etc.

Most people don’t realize that U-M holds the largest and deepest collection of papyri and related ancient items in the Western hemisphere. How did this collection take shape?

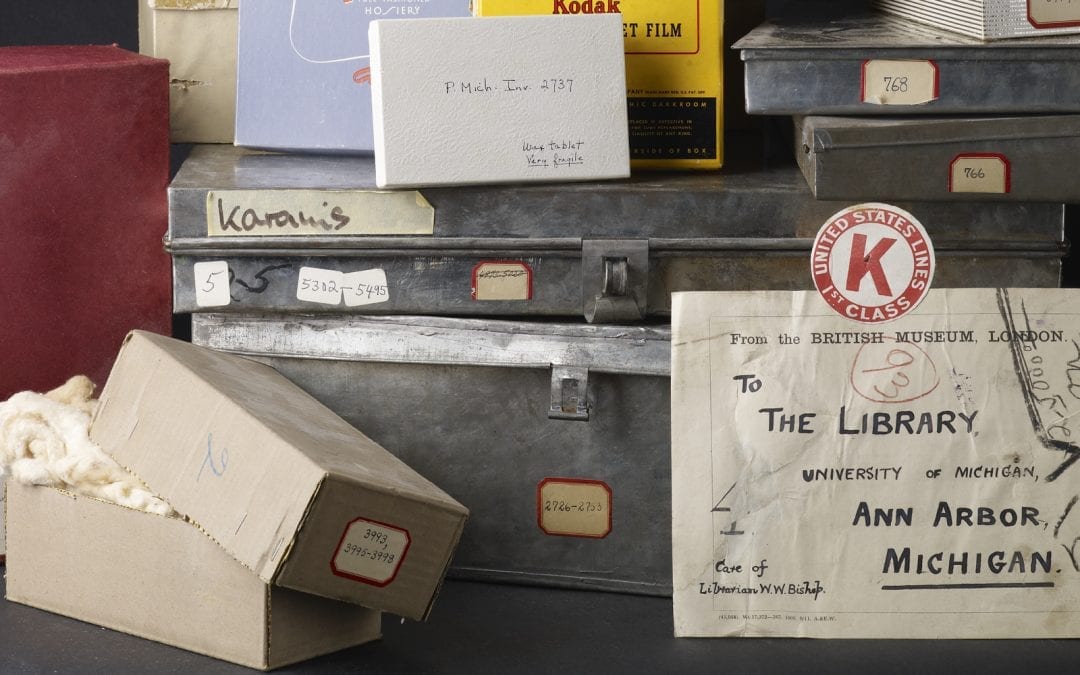

AV: The collection goes back to the vision and fundraising efforts of Francis Kelsey, professor of Latin at the University of Michigan in the early 20th century. He wanted his students to not only read about the ancient world in the works of classical authors such as Herodotus and Tacitus, but also to be able to experience it by looking at objects from daily life, and seeing actual manuscripts and papyri. He encouraged U-M to purchase a representative teaching collection, and Kelsey’s purchases form the core of what nowadays is the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology and the Special Collections and Papyrology Collection in the U-M Library. Kelsey himself made the first purchase of papyri in the spring of 1920. In addition, Kelsey advocated for U-M to initiate actual excavations, and in 1924 the university began excavations at the site of ancient Karanis, a village in Egypt, about 80 miles southwest of Cairo. During these excavations, which would continue until 1935, several thousands of papyrus fragments found in the houses and streets of this village entered the collection for study and publication with the expectation that they would be returned to Egypt upon request by the Egyptian authorities. (Indeed, a large portion of the Karanis papyri was returned to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo in 1953.) It is perhaps interesting to note that the first two excavation seasons at Karanis were funded by Horace Rackham, so that there is a clear connection between the papyrus collection and the Rackham Graduate School.

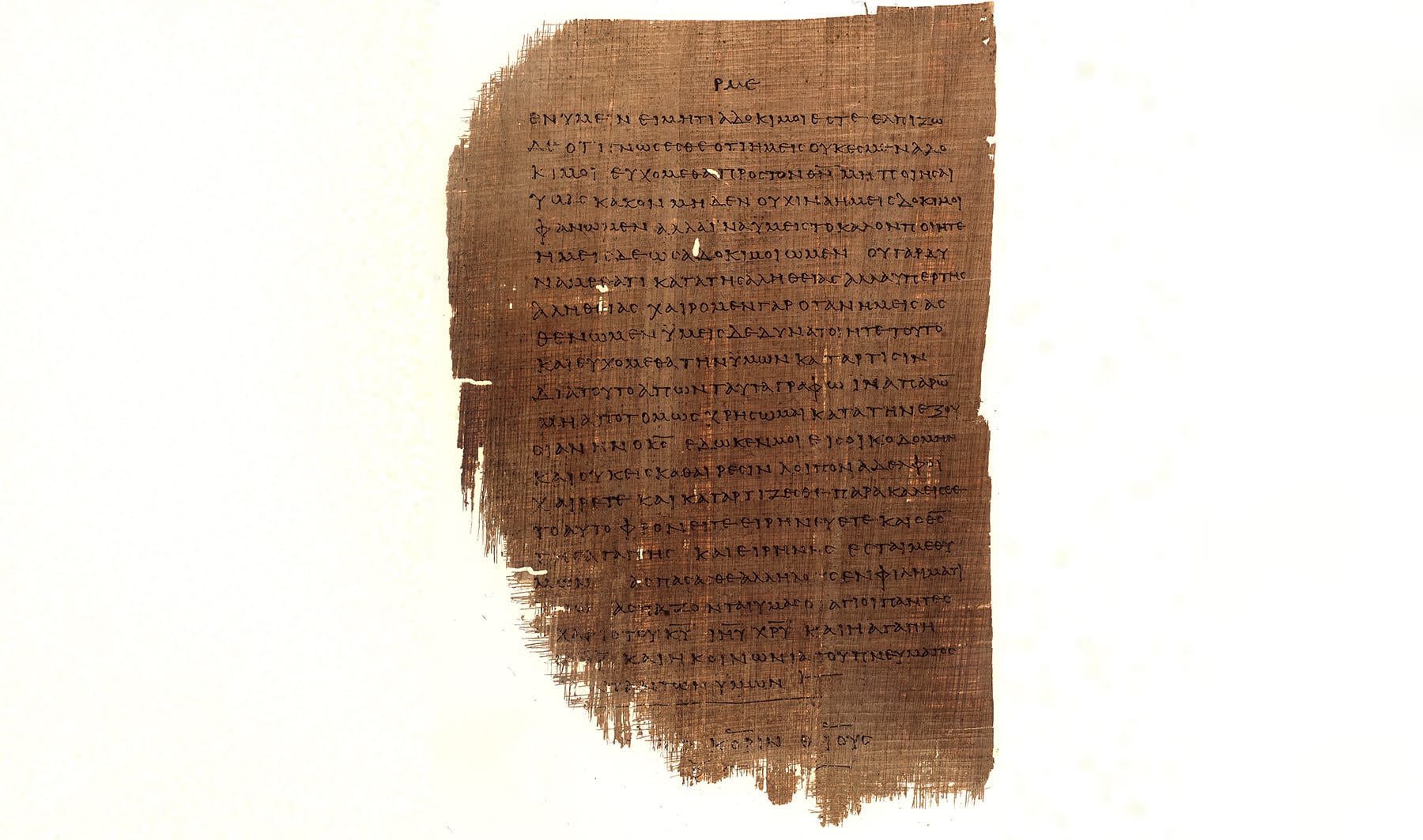

Inventory 6238 is one of the most studied and visited papyrus manuscripts of the Michigan collection: 30 leaves of an early codex that contained the Pauline Epistles.

What are a few of the most significant items in the collection? And what are some lesser-known items of interest?

AV: With over 18,000 individual fragments of papyrus in the collection, each of which contributing something to our understanding of the ancient world and the people that lived in it, it is quite daunting to identify the most significant. The choice also depends much on what one is interested in. One of my favorites is the Karanis tax roll. Measuring over 100 feet, this is one of the longest Greek papyri to survive from antiquity, and it contains a day-by-day record of all tax payments made by inhabitants of the village Karanis in the year 173 CE. Basically, what we have is a telephone directory for this village for this year, and unlike modern telephone directories, the names of parents and grandfathers are also included, allowing the reconstruction of actual families. What’s more, we have similar lists from other years, so that we can compare the village inhabitants over the years. Another interesting text that was found in Karanis contains a list of ships that entered the harbor of Alexandria, with the names of the ships, their port of departure, and tonnage. This provides a wonderful vista into the world of long-distance trade in the second century CE. The most significant item in terms of requests for study and viewing are the collection’s 60 pages of a book that contained the Epistles of Paul. Dated to about 200 CE (that is, about 150 years after these letters were written), these pages are the oldest manuscript of this text existing in the world today.

In writing this book, how did you balance writing for both scholars and a more general audience?

AV: From its earliest beginnings at the end of the 19th century, the field of papyrology has reached out to general audiences. It is interesting to see that the first generations of papyrologists publicized their newest findings in newspapers and periodicals before writing the more scholarly publication. And this is not strange. Many of the texts that papyrologists deal with are very relatable for contemporaneous readers. Seeing and reading a letter sent home by a recently enlisted Roman soldier, including his worries about family well-being and the dangers of war, is something that is timeless. Holding an actual school writing exercise that somebody kept because they contain the first letters ever written by a child is something we still do today. Or at least I do. So there is broad interest from general audiences in what papyrologists do, and in the texts they read, translate, and interpret. The trick is to make each text understandable for somebody who does not have the technical background that a professional papyrologist has without completely over-explaining and giving everything away. Part of the fun of being a papyrologist is the slow discovery of each text you study, from looking at the shape of the text and letters to individual letters, words, sentences, and some sort of understanding of what one individual in the ancient world was dealing with. I tried to provide enough information for each text so that readers could begin exploring the text themselves.

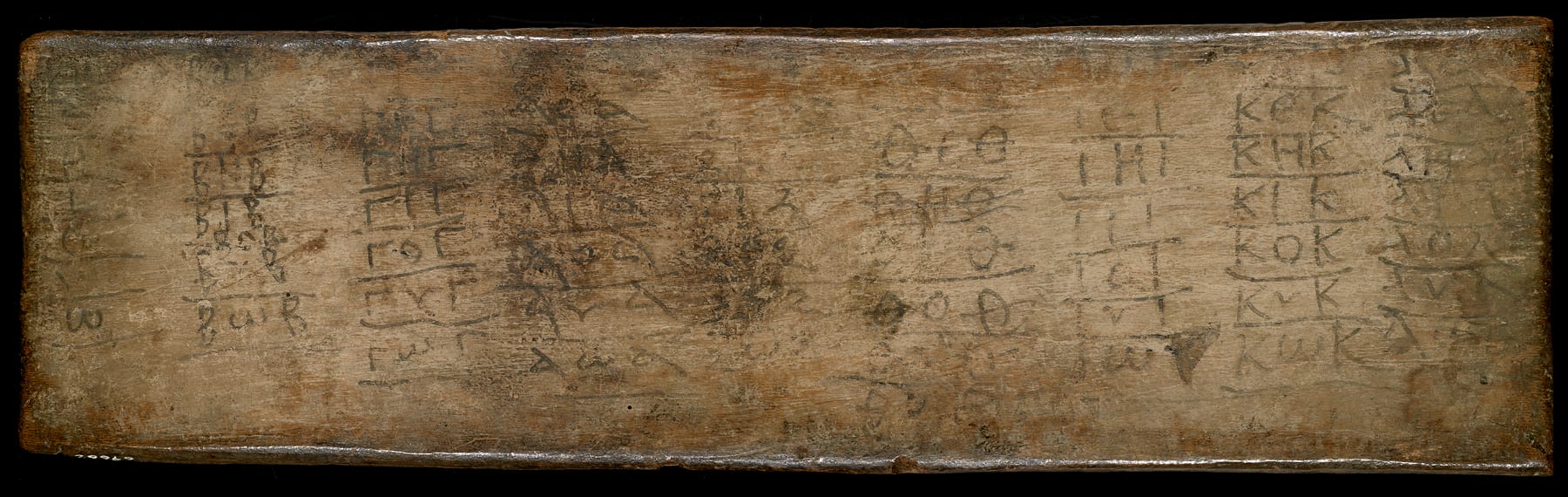

A student of Greek would begin to practice writing the rudimentary forms of letters. Although there are examples of such exercises on papyrus, the collection contains a number of examples on wooden boards, like this one, which could be washed and sanded for reuse.

What was the main impetus for writing this book? How does it complement the collection itself and images that are available online?

AV: The main impetus for this book were questions from visitors to the collection. The collection has a program of public outreach that allows members of the university community and members of the general public to visit the collection for a tour. During these visits, we put a number of items out for display, and one of the staff members gives an introduction to the collection and the items that are on display. People are always intrigued by what they see during such a tour when they get up close with ancient papyri. They wanted to learn more, and they often asked us where they could do so. We would point visitors to the website of the collection, and although there is a wealth of information there (and in other online resources), people felt it was difficult to arrive at a continuous narrative from disjointed webpages. The book provides a continuous narrative from which readers can venture out into the online world of papyrology (which is huge) and make even more discoveries.

Describe how you go about your own research in the field, and also how you manage that with the responsibilities of being an associate dean.

AV: Often, my research projects begin with opening a box with papyri that have never been studied in detail before. Yes, almost all texts currently in the collection have been entered in an online database with brief information about possible date and type of text, but the real discovery still needs to happen. The thing with opening a box is that you don’t know what you’ll end up with. This is exciting, but also quite unwieldy because you don’t know whether the text you will find has anything to do with what you have done before (other than that it was found in Egypt and written in Greek on papyrus). What I have tried to do after coming to Michigan is to approach texts in context. For example, in a 2013 graduate seminar we looked at one particular structure that was excavated in Karanis and only studied papyri that were found in that structure. Each student in the class prepared one or more documents from this structure for publication, and we just published a first result of this seminar, Papyri from Karanis: The Granary C123, which includes the individual contributions of the students. As to combining this with being an associate dean, I have found there is little time left to open a lot of boxes with papyri.

Arthur Verhoogt is an associate dean for academic programs and initiatives for the humanities and the arts at Rackham and an Arthur F. Thurnau professor of papyrology and Greek in the Department of Classical Studies.