On June 4, 1902, a British cargo ship arrived at Comodoro Rivadavia, a port city on the dusty Atlantic coast of Argentina’s Patagonia region. A weather-beaten group of families emerged onto the dock and made their way to the teams of oxen waiting to take them and their possessions on a trek 100 miles inland. These were Boers—white farmers of Dutch descent from the region that would eventually become South Africa—and for them, the dawn of a new century came with a new home, as well as the loss of an old one. From the farms they left behind on the other side of the ocean they brought little: what could fit on a cart and one other thing—their language, Afrikaans.

For the Boers who landed that day in Patagonia, as well as the estimated 650 others who would follow them by 1908, their language served as a key factor in their search for a new home. They hailed from the South African Republic and the Orange Free State, collectively known as the Boer Republics, which were established when Dutch-descended colonists left the Cape of Good Hope after it was taken over by the United Kingdom.

But when gold and diamonds were discovered in their new territory, the British Empire followed. By the end of the Second Boer War in 1902, the Boer Republics were no more, now simply the latest territories in the empire on which the sun never sets. Losing their farms and livelihoods in the conflict, many Boers were faced once more with the prospect of seeking out a new home. Among the reasons for their move, which also included the British ban on slavery, was the passage of new laws outlawing the speaking of the colonists’ Dutch-based Afrikaans language in schools, churches, and other cultural institutions. They chose to settle in dry, semi-desert Patagonia for its similarities to the home they had lost. While it has shrunk since the days of its founding—many of the Boer settlers were repatriated by the South African government in the 1930s—the community of their descendants, as well as their language, continues to this day among the windswept hills of southern Argentina.

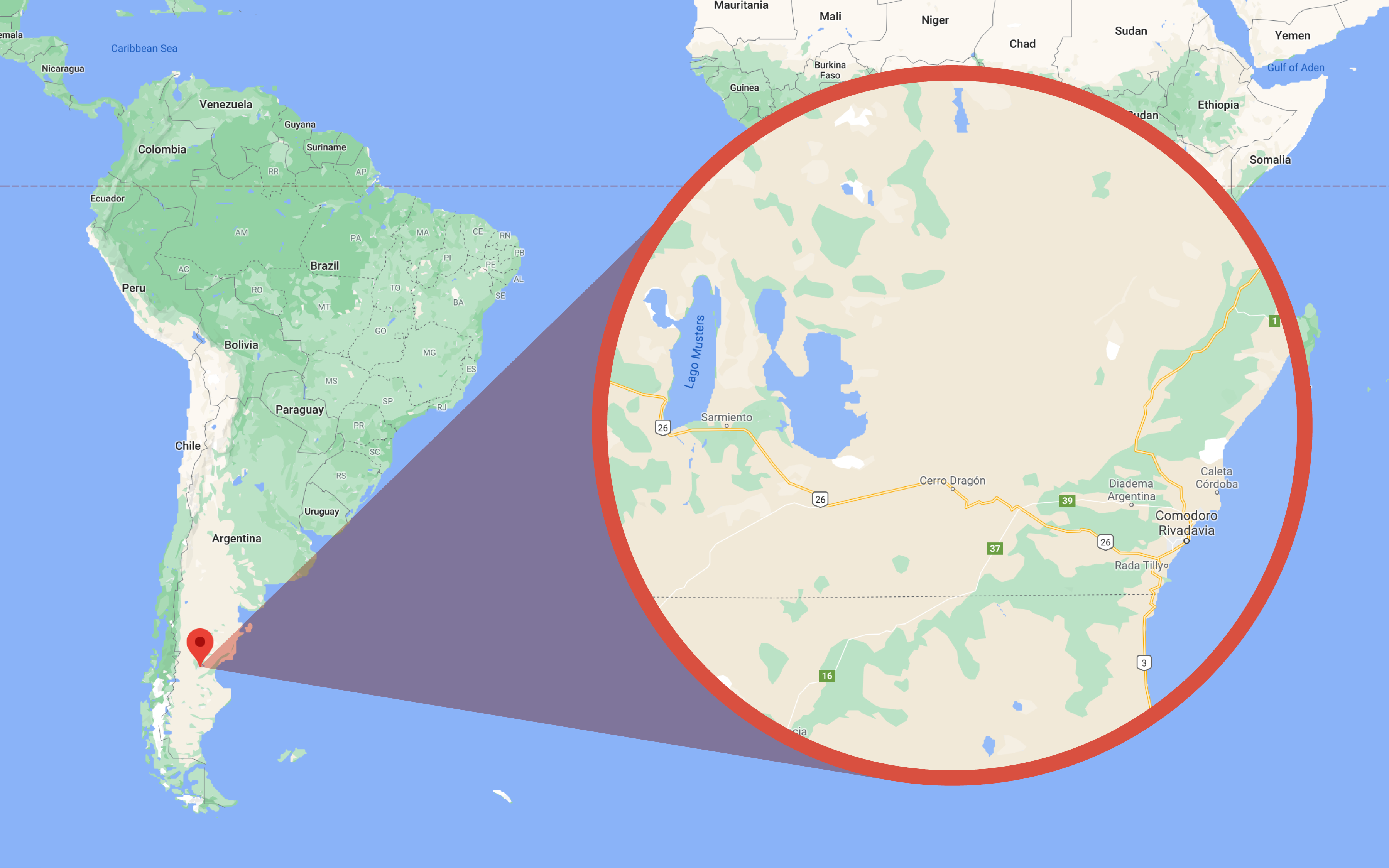

The Boer settlers landed in Comodoro Rivadavia on the Patagonian coast before migrating 100 miles inland to settle.

The passage of more than a century has changed much about the community. Life in the Spanish-speaking nation has seen fewer residents speaking Afrikaans, particularly among the younger generations as they seek to participate in the broader social and economic life of their country. Even those who do speak it generally reserve it for use within their homes. Retaining a language in such an environment this long is rare, however, so rare that a team of U-M faculty, graduate students, and undergraduate students is working to capture their Afrikaans before it disappears from the community entirely.

A Unique Team for a Unique Community

When he first learned of the Afrikaans community in Argentina, Andries Coetzee, a professor in the U-M Department of Linguistics and director of the U-M Africa Studies Center, knew he wanted to see it firsthand. An Afrikaans-speaker himself, he was interested in how and why the community had retained the language over such a span of time, and whether the prolonged exchange between Afrikaans and Spanish had altered how community members spoke either language. To do so, he would need help from colleagues with an intimate knowledge of Spanish, and so he reached out to Nicholas Henriksen, a professor in the U-M Departments of Romance Languages and Literatures (RLL) and Linguistics, and Lorenzo García-Amaya, an assistant professor in RLL.

“This is the most intriguing project I’ve worked on at the University of Michigan,” says Henriksen, the project’s principal investigator. “It revealed many fascinating narratives that touch not only on language, but also religion, cultural identity, race, isolation, and others. The community was excited to share their story with us, and to see that others in the world were interested in them in a way that didn’t exoticize them, but rather showed how they, as an immigrant community, were connected to the wider world.”

After a brief visit to Patagonia in 2014, Henriksen, Coetzee, and García-Amaya returned to Ann Arbor with questions they knew only a wide-ranging team of scholars could tackle. Around the same time, the U-M Office of the Provost launched the Michigan Humanities Collaboratory, which provides funding and resources for large, interdisciplinary humanities projects.

“The Collaboratory came at the perfect time for us,” Henriksen recalls. “We had an idea, we had a community eager to work with us, we had the momentum, and now we had a way to bring in everyone we needed to fill out our team’s expertise.”

Together, they formed the Argentine Afrikaans Collaboratory, a multidisciplinary, multigenerational research team dedicated to investigating and documenting the unique linguistic and cultural contact between Afrikaans and Spanish in Argentina.

Prior to COVID-19, members of the Collaboratory team worked with community members in Patagonia to record their use of both Afrikaans and Spanish. Photo by Richard Finn Gregory

Collaborative Success

While many research projects remained faculty-driven endeavors, the Collaboratory afforded graduate students the opportunity to take on important roles as equal collaborators, working on personally compelling aspects of the project as well as serving as mentors to its small army of undergraduate researchers.

Dominique Bouavichith, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Linguistics, joined the Collaboratory to help study one of its primary aims—the interplay between Afrikaans and Spanish. Bouavichith is a phonetician by training, a scientist who studies linguistic sounds and the physical processes that create them.

“The contact between Afrikaans and South American Spanish in this community is unique,” Bouavichith says. “We have a lot of data in linguistics to support the idea that humans communicate identity through sound, and that those differences can play an important role in distinguishing one group from another at a subconscious level.”

In order to search for ways that community members’ Afrikaans had been influenced by Spanish, and vice versa, Bouavichith analyzed speech from conversations the team recorded in the field, from bilingual speakers and from monolingual speakers of each language. He focused his attention on differences between the three groups in several key areas, including the acoustic vowel space— the variation in acoustic frequencies of vowels in different linguistic contexts—and intervocalic consonant reduction—the extent to which consonant sounds become weakened between vowel sounds.

Bouavichith’s work found that the amount that language contact has changed the way people speak both languages comes primarily from their age of language acquisition, with Spanish influences becoming more pronounced in speakers’ Afrikaans the younger they were when they first learned Spanish.

“This is fairly common in contact situations,” he explains. “We found older people had a much different relationship with Afrikaans than younger generations, who have a lot more exposure to Spanish. It’s similar to how I speak much differently from my grandfather, for example; it’s a natural process of generational change.”

While Afrikaans is quickly vanishing from the community, Henriksen points out they still take great pride in their South African heritage. Photo by Richard Finn Gregory

The analysis conducted by Bouavichith would not have been possible without the expertise of his colleagues. Micha Fischer, a Ph.D. student in the U-M Survey Methodology Program and graduate student research assistant in the U-M College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, helped with quantitative analysis and complex statistical modeling, and put together the surveys the team implemented to collect data in other projects.

Using a statistical technique called mixed effects modeling, Fischer harnessed a framework that allowed the team to compare how a speaker pronounces words from Afrikaans while speaking Spanish or Spanish words while speaking Afrikaans – called code-switching – against baseline statements entirely in one or the other language. The results paint a novel way of understanding how bilingual speakers’ two languages function cognitively.

“We’re interested in things like the intensity ratio between a consonant and a vowel,” Fischer explains. “Normally, as a statistician, the data you work with is fixed. Here, though, it isn’t necessarily; sometimes you have to go back and forth between the coded sound files where the data comes from and the model, and you need models that can account for the structure of the data and unobserved characteristics that vary from speaker to speaker. Collaboration among a well-formed team is essential to do this.”

A better understanding of how the community speaks Afrikaans today has also helped researchers piece together their origins. Due to confusion among historical records, the exact region in South Africa from which the original settlers migrated has been an open question, one Jiseung Kim, a Ph.D. student in Linguistics, believes their language can answer.

Afrikaans has two primary dialects, spoken in the northern and southern regions of South Africa. In delving into the team’s library of recorded conversations with the community, Kim and a group of undergraduates discovered the presence of transitional glide sounds, an additional sound added after a consonant and before a vowel, in the Afrikaans spoken by the Patagonian community. While this is also a linguistic feature of the southern dialect of Afrikaans, it is not present in the northern dialect.

“Different sources say different things about where they originally came from,” says Kim, who recently presented the team’s preliminary findings at the Mid-Continental Phonetics and Phonology Conference in Chicago. “Some say they were from near Johannesburg, others from farther south. By finding the use of transitional slides in their Afrikaans—and assuming, of course, the dialect zones in South Africa haven’t changed a lot in the last century—we have new evidence to support the idea that they came from the southern areas of the country.”

Their Place in the World

Afrikaans is a language with a troubled history. To most people, it’s known as the language spoken by South Africa’s oppressive apartheid regime and those who most benefited from it. Through the work of the Argentine Afrikaans Collaboratory, however, the story of a different, oft-overlooked community of Afrikaans-speakers has come to light.

In March 2020, immediately prior to the widespread travel lockdowns caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, Fischer accompanied Henriksen, Coetzee, and García-Amaya on a trip to South Africa. They presented a documentary about their work in Argentina at Woord Fees, a week-long celebration of Afrikaans language arts, and answered questions from the audience. For Fischer, it was an opportunity to see the deeper history behind the language he had spent over two years exploring.

“I didn’t know a lot about the history of Afrikaans, or the negative connotations it has because of apartheid,” he says. “For a lot of speakers, just speaking their own language comes with this additional burden because they don’t want to remind people of this hurtful legacy. As a statistician, you’re often so remote that it feels like it doesn’t matter where the data come from, but here I had the opportunity to see how complex everything is, and add my voice to that story.”

Rather than a reminder of a painful past, for the Argentine Afrikaans community it has become a symbol of their fortitude in the face of trial and hardship.

“Their settlement in Patagonia wasn’t easy, but they’re proud to have persevered,” Henriksen says. “Even among those who don’t speak Afrikaans, they feel it as part of their sense of place and identity. And I’ve seen that pride lead the younger generation to learn more about South Africa, the painful, thorny history there, and reconcile it with their own. In a lot of immigrant communities, at the third or fourth generation the culture isn’t as strong. But here, thanks in part to the preservation of the language, it’s palpable.”

Video by Richard Finn Gregory

Read more about the team, its findings, and the Argentine Afrikaans community at the project website.

How Rackham Helps

Bouavichith is the recipient of Rackham Graduate Student Research Grants, and has participated in multiple Rackham professional development workshops, as well as a discussion series on LGBTQ issues in the academy.

Fischer is the recipient of two Rackham Conference Travel Grants to attend the European Survey Research Association conferences in Lisbon in 2017 and Zagreb in 2019. He also received Rackham Graduate Student Emergency Funds during the COVID-19 pandemic and attended several Rackham workshops during his first year to better acclimate to U-M and life in the United States.

Kim is a recipient of the Barbour Scholarship, enabling her to spend an entire year focused on her research. She says she also enjoys using the study spaces in the Rackham Building.