Few kids can say they came up with the topic for their dissertation when they were six years old, but Erina Baci knew she wanted to be an archaeologist well before she could properly pronounce the word. Born in Albania, she moved to Canada with her family at a young age, but her parents never let her forget the story of the place they left behind.

Baci’s father hails from the Korca region of Albania, home to the Tombs of Selca e Poshtme, an Iron Age collection of royal tombs dating to the fourth century BC and one of the most significant archaeological sites in the country. He raised his daughter on stories of the Illyrians, a group of tribes that inhabited much of the western Balkans, including Albania, in antiquity and about whose deeds in battle tales have been spread since the days of Plato and Aristotle.

“The older I got, the more interested in archaeology I became,” recalls Baci, now a doctoral student in archaeology in the University of Michigan Department of Anthropology. “The prehistory of my country is what got me interested, and the intrigue has never left me. When the time came, I applied to the University of Toronto, majoring in archaeology.”

The Rest Is History

After completing her undergraduate degree, Baci pursued a master’s degree at Mississippi State University under the supervision of Michael Galaty, now the director of the University of Michigan Museum of Anthropological Archaeology (UMMAA). Baci’s thesis project revolved around using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) technology to analyze the distribution of archaeological sites across Albania, ultimately producing a comprehensive map of how the country was settled over the course of its history. Recalling her work in Albania and interest in the Balkan region, Galaty invited Baci to apply for graduate school at U-M, where he and his UMMAA colleagues were about to begin a new, long-term research project in the mountainous districts of western Kosovo, also known as Kosova in Albanian.

“Erina is not just a gifted technician, she is also well-versed in contemporary archaeological theory,” says Galaty. “She wants to study the ancient Illyrians. Identifying ethnic groups in the archaeological record is always complicated, but given her training, she is certainly up to the challenge.”

After decades of Yugoslavian rule and years of unrest and civil war, Kosovo won its independence in 1999. As the young nation begins to leave that tumultuous period behind, new opportunities to study its past have emerged, opportunities Galaty and Baci intend to seize.

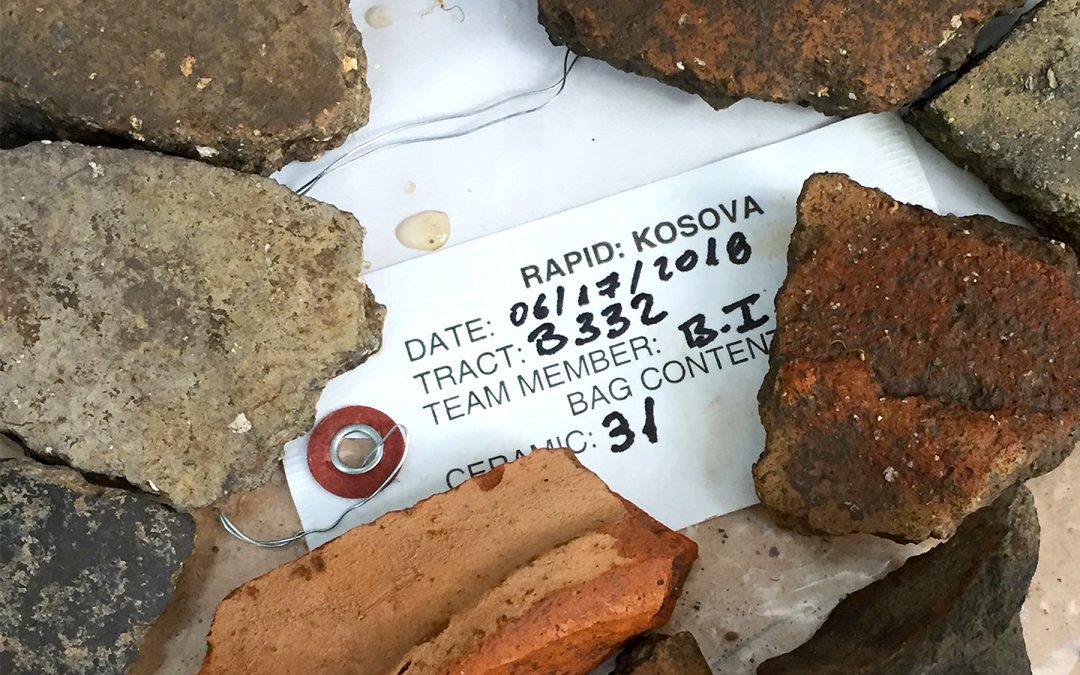

The project, Regional Archaeology in the Peja and Istog Districts of Kosova (RAPID-K), is a joint endeavor led by U-M in collaboration with the Archaeological Institute of Kosova and the Kosova Ministry of Tourism and Culture. An extension of two previous archaeological projects led by Galaty in Albania, RAPID-K unites archaeologists from U-M and the University of Pristina in Kosovo behind a goal as ambitious as it is simple: to understand the entirety of human history in Peja and Istog from the Bronze Age to the present.

While Peja and Istog have been the subject of several projects by local archaeologists since the 1970s, this marks the first time an intensive archaeological survey has been conducted there.

“Kosovo is a new country, and it’s just coming out of a very difficult period in its history,” says Baci. “We have an opportunity now to give people there a better idea of their own history through archaeology.”

Surface Pros

Though the image many have of an archaeologist is of someone kneeling in a shoulder-deep rectangular hole in the ground, coated in dust and scraping at the earth with a trowel to uncover artifacts, RAPID-K employs an innovative approach before engaging in such intrusive methods. Using a technique called intensive survey, Baci and her colleagues, armed with tablets and walking in evenly spaced lines, cover wide swaths of land and note any artifacts or historical features they encounter. Survey teams generally focus on agricultural fields, which often see many once-buried artifacts returned to the surface by farmers’ ploughs.

Back at the lab, Baci combines the data from each survey team into a single digital database, which she uses to look at the locations of concentrations of archaeological material. This will help RAPID-K conduct future excavations in a more strategic manner.

“The switch to using survey methods first reflects a change in the mentality of archaeology,” Baci says. “Excavation, while extremely useful, is a destructive practice; running surveys lets us gather regional data to answer specific, and important, questions, while preserving as much of the record as possible.”

This approach is already bearing fruit. During their first field season, the RAPID-K team discovered 13 previously unknown archaeological sites and recovered numerous artifacts from both the historic and prehistoric periods, including pottery fragments dating from the Neolithic to the time of ancient Greece and Rome. Baci is now integrating these data into the team’s database and mapping systems in order to guide their activities when they return to Peja and Istog next summer.

“While we are in Kosovo, Erina runs our computer and satellite systems, manages our databases, and surveys all day, every day,” Galaty says. “During the rest of the year, I turn to her constantly for help running our project. It’s no exaggeration to say RAPID-K could not function without her.”

For Baci, working to uncover the past of a region so closely tied to her own is reward enough. Her dissertation will focus on RAPID-K’s work in Kosovo, and she plans to continue to explore the historic and prehistoric past of Albania and Kosovo upon completing her program.

“There’s something amazing about being out in the field,” she says. “Archaeology gives us a window into the past that history often can’t, and the idea that I’m able to contribute to the creation of that knowledge is very fulfilling. My curiosity and love for the past absolutely drive me.”

How Rackham Helps

Baci is the recipient of two Rackham conference travel grants, enabling her to present the results of her master’s thesis work at the January joint meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America and Society for Classical Studies, as well as at the annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology.