Cheewit nay Israel (“Life in Israel” in Thai) is a web series produced by Israeli workers’ rights organization Kav La’oved, Louiz Green of GLV Productions, and myself, for the benefit of farmworkers from Thailand who are working in Israel. These workers—who number around 22,000 and do the bulk of the labor in Israel’s agricultural sector—face linguistic, cultural, and geographical isolation and their legal rights are routinely violated. Kav La’oved (“Workers’ Hotline” in Hebrew) and several other NGOs are committed to helping farmworkers organize for their rights, but sometimes have a hard time reaching workers. My inspiration for the series was an encounter I had while doing fieldwork in Thailand, when I was invited to answer questions at a training seminar held by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) for workers about to depart for Israel. The general mood at the seminar was jovial, and besides serious questions about legal rights and contract language, I also got more light-hearted queries about the availability of lao khao liquor and the legal status of buckets on vehicles, in reference to the rumors about a government decree against motorized water-splashing on the upcoming holiday of Songkran.

Despite getting indispensable help from my research coordinator and interpreter, Phii Mii, I hadn’t been able to answer all the questions posed to me that day, and imagined that if this group of several dozen people on their way to Israel had questions, the 22,000 Thais who were already there might have quite a few more. So I teamed up with Sophie Shannir, Coordinator for Agricultural Workers at Kav La’oved, to suggest to Rackham a Public Scholarship project aimed at reaching the maximum number of migrants, who could ask us questions and receive questions via the internet. Deducing from my experience with the IOM trainees, we expected to get a random assortment of questions, some serious, some funny. Keeping in mind the importance of sanuk (fun) as a principle of social interaction in Thailand, Kav La’oved’s fieldworker and translator Adi Bachar, our director Louiz Green, and I put together a humorous, tongue-in-cheek teaser video in which we invited workers to send us questions.

Figure 1: Screenshot from the “Cheewit nay Israel” teaser. L: Adi Bachar of Kav La’oved. R: The author

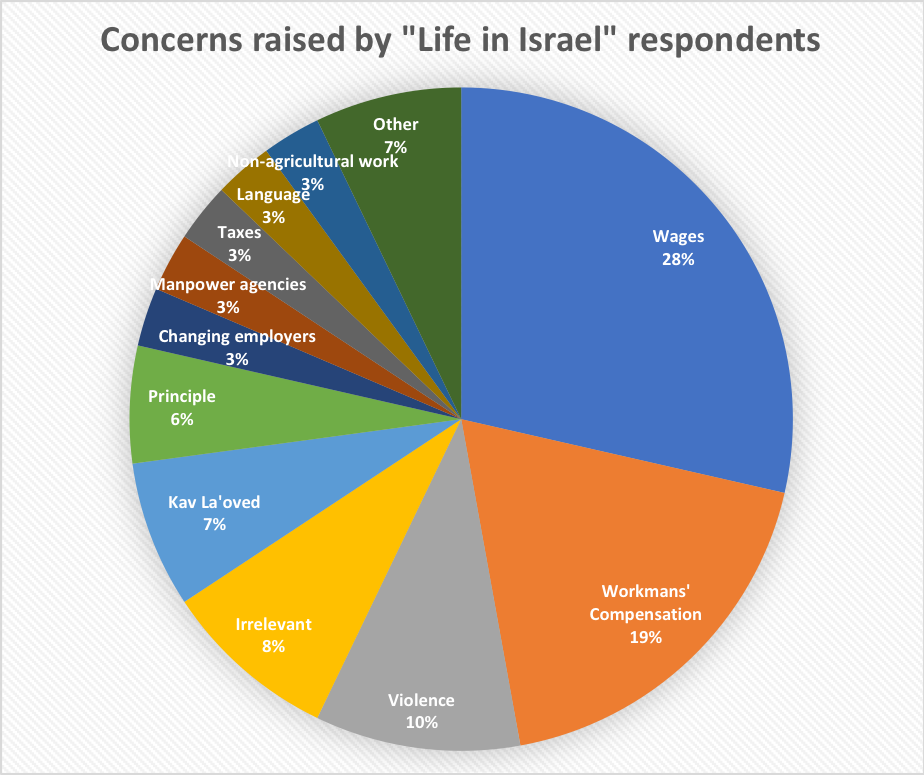

The results we got were sobering (see Figure 2). Of the 63 people who responded to our teaser on Facebook, only a small handful posted irrelevant comments, and nobody asked questions of a frivolous or light-hearted nature. Almost half the questions had to do with monetary concerns – either wages or the compensation due to workers upon finishing their contract. Most other questions also had to do with legal issues, such as the procedure for changing employers, or the legality of requiring workers to do non-agricultural work. Most respondents seemed painfully aware that their legal rights were not being respected, some even waxing quite cynical. In response to a worker who wrote that “90 percent of workers are not paid according to the law,” another answered: “The Thai government said in a statement that in fact less than 5 percent are paid below the minimum wage. Unfortunately, we happen to be employed by this 5 percent of employers!” and added “555555,” online slang for laughter.

Figure 2: Concerns raised in the 63 responses to our teaser. N=70 (some responses included more than one concern)

These questions were eye-opening for me. My dissertation fieldwork on the relationship between migrants and their employers had awoken me to the many ways in which Thai workers are exploited, but also to the apparent normalcy of this exploitation. When in interviews I had ventured to ask migrants what they thought about such issues as wage law violations, I always got muted responses. Though I realized that these reactions had much to do with me being an Israeli and thus associated in some way with the employers, I wasn’t expecting to get such different reactions on Facebook. Despite the lack of anonymity, apparently the use of the Thai language and the involvement of a group known for standing up for migrant workers’ rights, Kav La’oved, led workers to feel safer disclosing angry feelings than they had in interviews with me.

Upon seeing the seriousness of the questions we received, the production team realized that we would have to take a more serious tack in order to tackle them respectfully. We donned jackets (see Figure 3) and put together two episodes concentrating on the two most salient concerns, wages and compensation, and a third one in which we tried to cover as many of the other questions as we could. One aspect of the videos—my absolutely horrible pronunciation in Thai—will probably still prove funny to viewers and will hopefully contribute to the videos’ virality. Chapter 1 will be coming out soon, and I’m eager to see what kind of reactions we get.

Figure 3: Screenshot from a working version of Chapter 1 of the “Life in Israel” web series

The Rackham Program in Public Scholarship (RPPS) supports collaborative scholarly and creative endeavors that engage communities and co-create public goods while enhancing graduate students’ professional development. We support graduate students looking to deepen their public engagement through four core offerings: The Institute for Social Change, Engaged Pedagogy Initiative, Grants in Public Scholarship, and Rackham Public Engagement Fellowships in sites across Southeast Michigan – all to support research, teaching, and projects that reach public audiences and foster impact beyond the classroom.

The views expressed in this post are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of Rackham Graduate School or the University of Michigan.