Debuted in 1903, The Atonement by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor is likely the first work of its kind ever written by a composer of color. Now, Rackham and School of Music, Theatre, and Dance (SMTD) student Bryan Ijames is leading a project to create the first full recording of the piece—which has not been performed in its entirety in over 100 years.

The Atonement is a sacred cantata for soloists, chorus, and orchestra. While the vocal score has long been widely available, the orchestral score was never published or digitized. That set Ijames on a journey of discovery, with the hopes of reintroducing the work to modern audiences and drawing attention to its immense importance in equalizing BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) representation in the choral canon.

“Acquiring a quality first recording is imperative to highlight the monumental nature of this work and help encourage future performances.”

“I began an arduous search for anything related to this piece,” Ijames says. “After not locating any performance recordings, talking with numerous Black music scholars, and spending countless hours reading about it, I started sending emails to the United States Library of Congress, which was said to have had string parts; the Three Choirs Festival Archives [The Atonement’s commissioning organization]; and the Royal Albert Hall in search of a full score. And when nothing was found, I had to dig deeper. Coleridge-Taylor was a student at the Royal College of Music in London, and upon contacting their archival library, I hit the jackpot—there sat the autographed manuscript, his original score.”

Because The Atonement is in the public domain, Ijames says, the library was happy to scan the documents and digitize them on the International Music Score Library Project.

From the Royal College to the White House

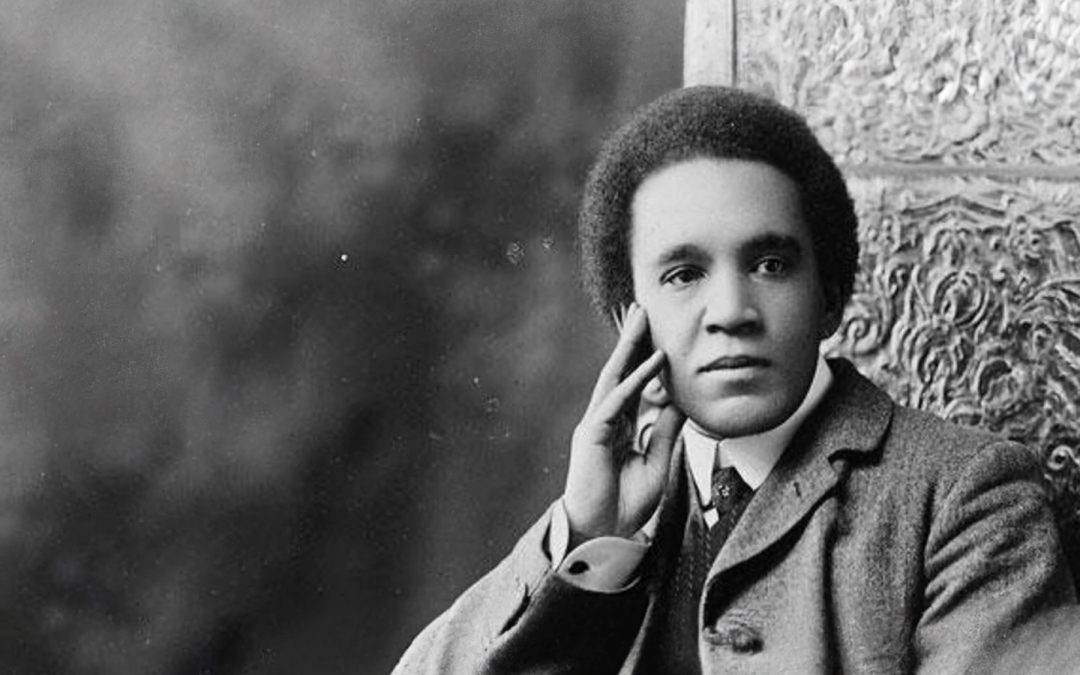

Coleridge-Taylor was born in London in 1875 to a white Englishwoman, Alice Hare Martin, who named her son out of admiration for the Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. His father, Daniel Hughes Taylor, was a Black student from Sierra Leone who met Martin while pursuing medicine in England. He returned to Africa around the time Coleridge-Taylor was born.

Martin’s side of the family boasted several musicians, and her father taught Coleridge-Taylor to play the violin when he was young. Despite the challenges of growing up in Victorian society as the mixed-race child of an unmarried mother, his skill as a musician propelled him to the Royal College of Music at age 15, with contemporaries like Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams. He switched his course of study to composition two years later.

After Coleridge-Taylor made his debut at the Three Choirs Festival in September 1898 with “Ballade in A Minor,” an influential music editor and critic of the time labeled him “a genius.” Two months later, his most recognized work, Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, premiered and went on to earn him fame that led to three tours of the United States. During the first such tour, in 1904, he was invited to the White House by President Theodore Roosevelt. He produced more than 80 compositions before his death from pneumonia in 1912 at age 37. Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast continued to be performed extensively during the early decades of the 20th century, rivaling the popularity of Handel’s Messiah and Mendelssohn’s Elijah.

Ijames already holds three degrees in musical disciplines. “I have been singing for many, many years and always wanted to do a terminal degree in this field,” he says.

“I’ve Struck Gold!”

“He wrote operas, many choral orchestral works, a symphony, chamber music,” Ijames says. “Our studio was given an assignment to find and present a piece of music by a person of color that wasn’t based in spirituals, gospel, or jazz. After perusing Marques L.A. Garrett’s indispensable Non-Idiomatic Choral Music of Black Composers database, I stumbled upon the vocal score. Besides the kinship of racial identity with Coleridge-Taylor I feel, the music he composed is extraordinary and stands alone.”

Ijames holds master of music degrees from Mississippi State University and Eastern Kentucky University, and he earned his bachelor’s in voice from High Point University. He is currently a doctoral candidate in choral conducting and was drawn to Michigan to work with celebrated Professor and Director of University Choirs Eugene Rogers (M.Mus. ’01, A.Mus.D. ’08). Rogers, Ijames says, has provided extensive encouragement and mentorship in diversity of programming and research. While Ijames hadn’t initially planned to do such in-depth research toward fulfilling the requirements of what is technically a performance degree, the sheer wonder and mystery of the lost orchestral score drove him on. Once he found it, the scope of his original project grew.

“My initial thought was, ‘Wow, I’ve really struck gold!’” he says of the shock of seeing just the first page of the orchestral score for the first time. “Not gold in the monetary sense, but an unbelievable and remarkably rare gem that frankly was ‘lost in the stacks’—known to some, but largely forgotten by most. With this score, I can reintroduce this work to the world.”

Ijames had originally thought he would only produce a version for a smaller chamber orchestra, but he realized the difficulty of doing so without first experiencing the composer’s full orchestration. While he still hopes to complete a reduction, he changed his current focus to producing a full recording and named the project “Unearthing a Lost Score: Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s The Atonement.”

“Acquiring a quality first recording is imperative to highlight the monumental nature of this work and help encourage future performances,” he says. “The goal of this performance is not only to resurrect Coleridge-Taylor’s masterpiece, but to integrate it into the larger canonic field of music.”

Hill Auditorium, the performance venue, is named after former university regent Arthur Hill, whose tenure (1901 to 1909) coincidentally overlapped The Atonement’s original 1903 performance. Photo: Austin Thomason, Michigan Photography

Passion Project

Staging the performance has required extensive outreach and logistical coordination, including securing Hill Auditorium as the venue, which Ijames says is a rarity for doctoral students who aren’t organists. He is the teacher of record for U-M’s Arts Chorale ensemble, whose members will perform as part of their concert series. But the scope of the piece calls for many more artists to be involved. To add a spirit of community engagement, singers from Ann Arbor’s First United Methodist Church, where Ijames is Chancel Choir Director, will also take part. He also reached out to choral groups in Detroit and elsewhere in Ann Arbor to bring the total choir number to around 120. The orchestra will comprise music majors from SMTD, and feature six soloists who are current SMTD students or alumni.

Ijames says that The Atonement itself combines elements of a passion, an oratorio, and a cantata. It’s a dramatic telling of the story of Christ, set to music. Ijames describes it as having a sense of “overwhelming grandeur and freshness.”

“I told the Arts Chorale that we’re at a public university, and I’m not here to teach religion,” he says. “We are approaching this from the historical point of view, from a point of view of highlighting underrepresented composers, contributing to inclusion and equity, and restoring things that have been forgotten.”

And after all he has done to create this edition, what will it be like for him to stand in front of the full orchestra and choir on Hill’s famous stage to conduct a work that has not been heard for more than a century?

“I hope I can make it through, because I get emotional just thinking about it.”

This performance took place on March 16, 2023. A recording is currently being edited, and a link to it will be available from this article later this summer.

How Rackham Helps

Ijames says that funding from Rackham has played a role in each step of this project. The Atonement manuscript, a handwritten score, required the help of a professional music engraver to create modern performance materials. As a pre-candidate, Ijames used a Rackham Research Grant to help him get the score engraved. “To prepare the score for performance and possible publication, it would take a qualified music engraver an estimated 60 hours to engrave the almost 350-page full score,” he says. “Completing a project of this magnitude at the most accurate level requires expertise outside of my training and experience.”

Upon achieving candidacy, Ijames received another Rackham Research Grant that will be put toward honorariums for the ensemble chorus and orchestra.

Ijames notes that this project would not have been possible without the generous financial support of other university departmental grants, private donors, and regional arts organizations: the U-M Arts Initiative; the Center for World Performance Studies; the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies; the Office of Academic Multicultural Initiatives; the SMTD Eileen Weiser EXCEL Fund; the SMTD Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion; and the Sphinx Organization.